Chronic kidney disease (CKD) requires patients to participate in an adaptation process, which may be facilitated with the support of healthcare professionals and trained peers. The objective of this study is to present the implementation of a pilot patient mentoring programme to promote adaptation in patients with CKD.

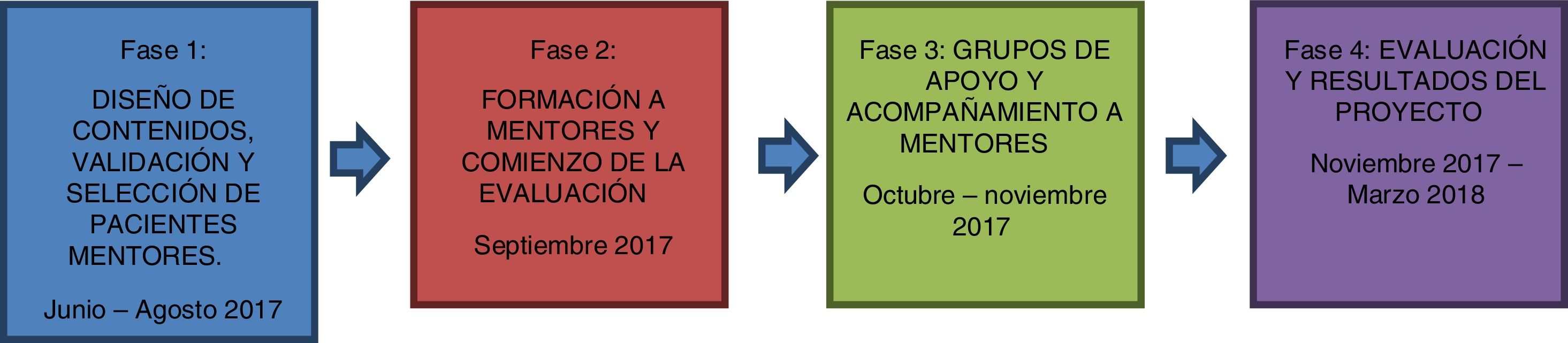

Materials and methodPre-test-post-test design (quantitative and qualitative). The study was carried out in six hospitals in Spain. The instruments used to measure impact were ad-hoc scales (10-point Likert scale response format) on satisfaction and skill acquisition, as well as the creation of focus groups with eight patient mentors and 10 healthcare professionals. The programme was split into four phases: 1. Design and validation of the manualised programme's content, and selection of patient mentors; 2. Mentor training, satisfaction with training and skills acquired by the mentors; 3. Implementation of mutual support groups and profile of those attending these mutual support groups; 4. Assessment and results of the Mentoring programme.

ResultsIn total, 39 mentors were trained on group management skills, as well as how to provide emotional support. 22 support groups were held, with 121 participants (22% carers). 65% of the patients were attending the CKD clinic. 65% of the participating patients considered making some form of lifestyle change after taking part in the programme. All the items assessing satisfaction and usefulness scored very highly, achieving 8.5 out of 10 or above.

ConclusionsThis is the first manualised mentoring programme in CKD to be undertaken simultaneously in six Spanish hospitals. The manualised and highly structured nature of the programme make it easy to replicate, minimising the risk of error.

La ERC (Enfermedad Renal Crónica) requiere de un proceso de adaptación en el paciente, que se puede facilitar con el apoyo de los profesionales sanitarios, así como por iguales capacitados. El objetivo de este estudio es presentar la puesta en marcha un programa piloto de paciente mentor para promover la adaptación de los pacientes con ERC.

Materiales y métodoDiseño mixto (cuantitativo y cualitativo) pre-post. El estudio se llevó a cabo en seis hospitales de España. Los instrumentos utilizados para medir el impacto fueron escalas elaboradas ad-hoc (formato de respuesta escala Likert de 10 puntos) de satisfacción y adquisición de competencias, así como la creación de grupos focales con 8 pacientes mentores y 10 profesionales sanitarios. Se dividió el programa en cuatro fases: 1. Diseño y validación de contenidos del programa manualizado, y selección de pacientes mentores; 2. Formación a mentores, satisfacción con la formación y competencias adquiridas por los mentores; 3. Implementación de los grupos de apoyo mutuo y perfil de los asistentes a los grupos de apoyo mutuo; 4. Evaluación y resultados del programa de Mentoring.

ResultadosSe han formado a un total de 39 mentores en habilidades para conducción de grupos, así como para facilitar apoyo emocional. Se han conducido 22 grupos de apoyo con 121 participantes (22% cuidadores). El 65% de los pacientes estaban en consulta de ERC. Un 65% de los pacientes participantes consideraron hacer algún cambio en su estilo de vida tras la asistencia al programa. Todos los ítems que evalúan satisfacción y utilidad han mostrado una puntuación muy elevada, por encima del valor 8,5 sobre 10.

ConclusionesEste es el primer programa manualizado deMentoring en ERC llevado a cabo de manera simultánea en seis hospitales españoles. La naturaleza del programa, manualizado y altamente estructurado, permite su replicabilidad minimizando el riesgo de error.

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Spain has grown by 20% in the last decade. It has increased from 1001 patients per million (ppm) in 2006 to 1211 in 2015 according to the Spanish Society of Nephrology (S.E.N.) register updated with the latest available data (S.E.N. Burgos 2017). The ENRICA-Renal study places the prevalence in Spain at around 15%.1 On the other hand, Spain is one of the European countries with the highest prevalence of CKD, only surpassed by Greece, France, Belgium and Portugal. A little over 4 million people suffer from CKD in Spain, of which just over 55,000 are undergoing renal replacement, with a much greater impact on men than women. 52% are with a functioning renal transplant and the remainder on dialysis.2

CKD is a disease that generates a wide range of stressful situations in the subject and his or her environment, causing both physical and psychological disorders.3 The evidence shows us that the medical treatment of chronic diseases in general, and of CKD patients in particular, is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition to achieve the adaptation of the patient, since there are other factors that affect the development of and coping with chronic disease.4 In short, we are facing an advanced progressive and incurable chronic disease, which is accompanied by a prolonged and interrelated symptomatology that requires an enormous effort of adaptation by the patient, and this adaptation can be facilitated with the support of the professionals who treat them, as well as trained peers.5

The implementation of a patient-led hospital mentoring program is an initiative that helps to incorporate the community into educational strategies and increases the sensitivity of professionals to the promotion of self-care and emotional support in a disease of long evolution.6

Let us not forget that the intervention and psychological support in chronic diseases demand models of enhancement of resources and skills (identifying factors that allow people to progress) rather than disease-oriented models. Incorporating a comprehensive perspective of care is only possible if clinicians assume the responsibility of incorporating patients as agents of change and give them a voice within the collective spaces of health care and its promotion.7

That is why, in the mentoring program, 2 cross-sectional educational axes were developed: emotional support in order to facilitate adaptation to CKD and promotion of self-care. Moreover, these educational actions are clearly justified if we remember that in strategic line no.° 3, of the Framework Document on CKD within the Chronicity Approach Strategy in the National Health System (SNS), it is highlighted the importance of incorporating mechanisms that encourage the active participation of patients.

The objective of this study is to present the implementation of a pilot mentoring patient program in 6 hospitals in Spain, to provide emotional support among equals and promote the adaptation of patients with CKD. This manuscript summarises all the activities and results obtained from the "Mentoring Program in the Chronic Renal Disease (CKD) Consultation" carried out during the months from June 2017 to May 2018.

Design, application, evaluation and resultsAgents involvedThe program was assisted by 4 types of agents:

- •

Health professionals (nephrologist and nurse) as prescribers and program advisors. The assistance team was the one who selected the mentor patients in each of the hospitals.

- •

The mentor patients who were trained to lead and direct the mutual support groups.

- •

Patients with "recently diagnosed" CKD and their relatives who were the recipients of the program.

- •

Trained psychologists who trained and provided support to mentoring patients throughout the different stages of the program.

To achieve the proposed objectives, the program was divided into 4 stages with differential and complementary methodologies (Fig. 1). Each stage is described in detail below:

Stage 1. Content design and validation and selection of mentor patientsIn this phase were designed and prepared, materials such as patient invitation texts (Appendix B See Annex 1, supplementary material), mentor training material, peer-to-peer session guides for mentors and the impact evaluation questionnaire. The contents were reviewed, adjusted and validated based on a panel of experts made up of 3 psychologists, 2 nephrologists and a biologist expert in the design of patient support programs.

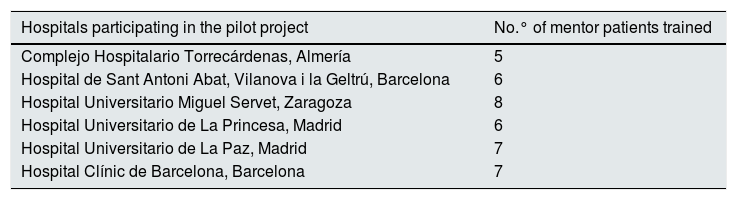

The selection of mentor patients by hospital was also carried out. Table 1 shows the participating centres and the number of mentors per centre.

Participating centres and number of trained mentor patients (N = 39).

| Hospitals participating in the pilot project | No.° of mentor patients trained |

|---|---|

| Complejo Hospitalario Torrecárdenas, Almería | 5 |

| Hospital de Sant Antoni Abat, Vilanova i la Geltrú, Barcelona | 6 |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | 8 |

| Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid | 6 |

| Hospital Universitario de La Paz, Madrid | 7 |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona | 7 |

The training for mentor patients consisted of 6 meetings where 2 intensive workshops were implemented in two 4-h sessions. The delivery of these workshops was led by a team of psychologists trained in "Skills for conducting peer support groups in CKD" and with extensive experience in chronic patient management.

Within this training 2 types of evaluations were carried out:

- •

Evaluation of satisfaction with the training received.

- •

Evaluation of skills acquired.

In order to obtain information to know how the training had been developed, about aspects related to the contents, the methodology and the teaching team, the attendees were asked for give their opinion by means of a mixed questionnaire: quantitative and qualitative.

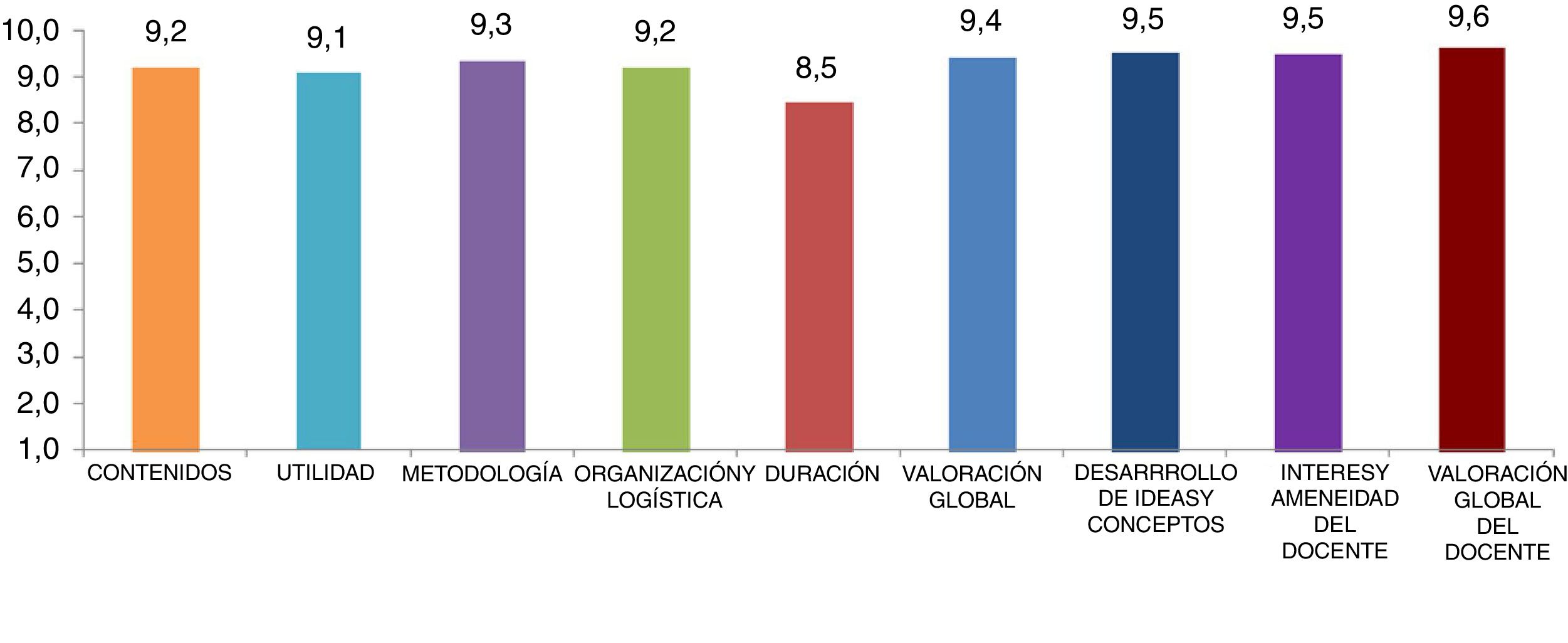

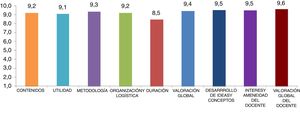

The quantitative part was composed of 9 items, which referred to the contents, utility, organization and logistics, duration and quality of the teacher.

The quantitative questions were measured through a 10-point Likert scale:

In general terms, all the indicators evaluated had obtained very high scores, as seen in Fig. 2. All variables, with the exception of the duration of the workshops, have been rated with scores higher than 9. The highest rated aspects were those that referred to the "content of the topics"; "the work method used" and "the organisation and logistics", obtaining an average of 9.2. The overall assessment of the training obtained a 9.4, very close to the maximum value.

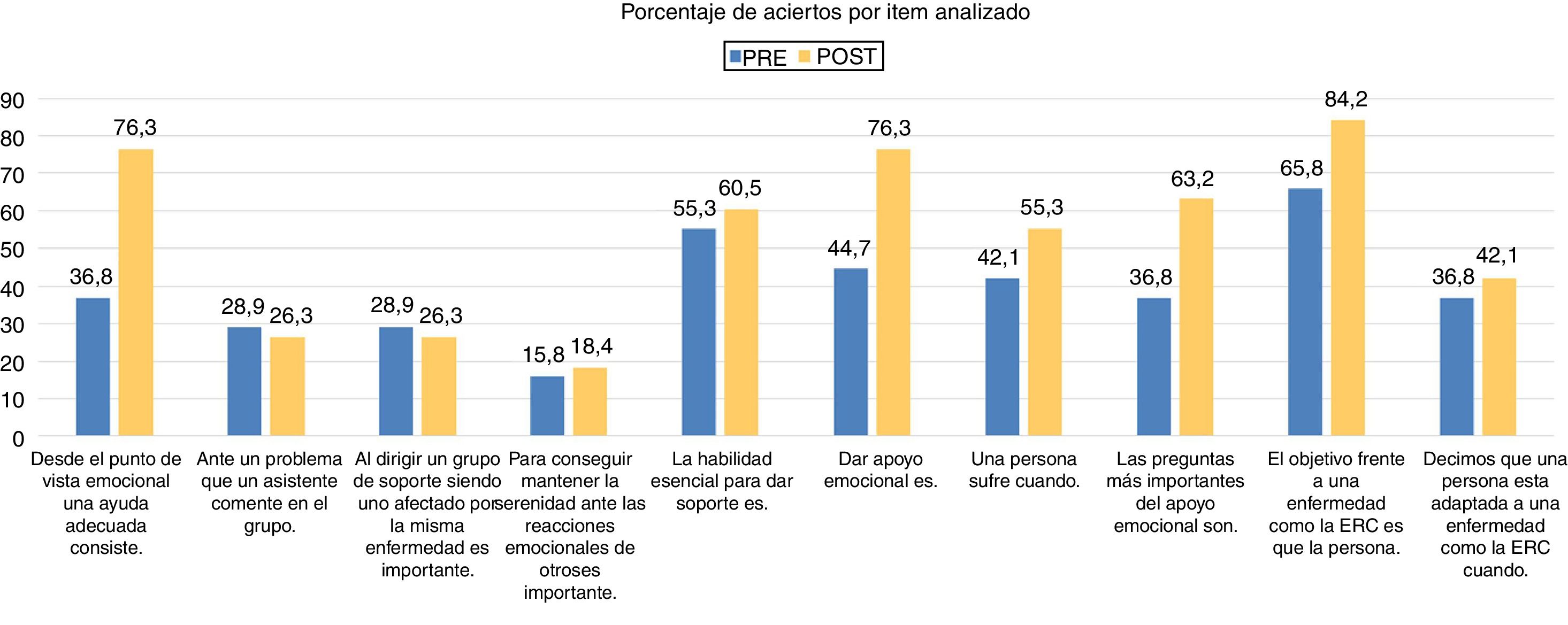

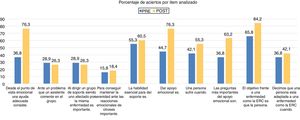

Evaluation and results of skills acquired with the training receivedTo assess the level of competencies (knowledge and skills) of the mentors acquired after the training, the attendees were given a situational questionnaire before and after the training that allowed them to know the capacity of those attending the training to carry out a "peer support" to groups of patients with CKD. The questionnaire consists of 10 items with 4 alternatives response. The PRE questionnaire was administered on the first day of in-person training and the POST questionnaire on the last day of in-person training. The 10 variables measured by this questionnaire are presented in Fig. 3. The items that experienced the greatest improvement were "that is to help adequately" (item 1) increasing the percentage of selections from 36.8% in the PRE questionnaire to 76.3% in the POST questionnaire, "Give emotional support" (item 6) from 44.7% in the PRE to 55.3% in the POST and "The goal in the face of a disease such as CKD is that the person" (item 9) that went from 65.8% of selection in the PRE to 84.2% in the POST. The results are shown by percentage of selections per item analysed (Fig. 3).

Stage 3. Implementation of mutual support groups and profile of the attendees to mutual support groupsIn this third phase, 22 CKD mutual support groups were launched in the 6 participating hospitals. Each mentor patient who held a group had a personalised telephone accompaniment carried out by psychologists specialised in the emotional management of chronic patients. The mutual support groups were structured in 3 sessions of one-hour each. The first 2 sessions were held by the mentor with the patients or caregivers who voluntarily signed up for the program to address the main concerns expressed by the patients and to facilitate coping resources. In the last session, the mentors had the support of a healthcare professional (mainly nurses) to address issues related to the care of kidney disease.

Between 2017 and 2018, 22 mutual aid groups have been formed reaching a total of 121 patients and caregivers in the phase of CKD or first months in dialysis treatment.

Profile of the assistants in the mutual support groupsA 52% of attendees were men. Attendees aged 61–70 were the largest group (30%) followed by those over 71 years old (28%). The age group that participated to a lesser extent was 41–50 years (9%). 70% of the participants were in a couple or married.

When considering this type of current treatment, 78% of the attendees were patients and 22% were family members. 65% of the patients were in the CKD clinics, 29% in haemodialysis and 6% in manual peritoneal dialysis. All attending patients had less than 6 months in the current technique and had no previous experience in another type of renal replacement technique. Of the 121 people who participated in the mentoring program, 78% were patients and 22% were caregivers.

Phase 4. Evaluation and results of the mentoring programThe mentoring program has been evaluated throughout the process to determine the impact and satisfaction of the program in the patients who have participated in the mutual support groups. The indicators evaluated were the utility, willingness to change and satisfaction in a quantitative way through an ad hoc questionnaire that was administered to the participating patients at the end of each group session. In addition, a qualitative POST evaluation was performed, after the end of most mutual support groups. Three focus groups were held that have allowed the viability and adjustment of the program to be expanded and deepened, including group interviews with both mentors and professionals who have participated in each healthcare centre.

Utility, willingness to change and satisfaction with the mentoring programTo evaluate the impact of the mutual aid groups, the attendees were asked about the utility or contribution that the sessions had had in their day to day life. To which 97% considered that the program had contributed something to their day to day life with the disease. Given the qualitative question about what it had done for them, the answers they gave were categorized into 6 non-exclusive categories: knowledge of kidney disease, disease, safety, normalization, peace of mind, improved coping, increased self-care awareness and the reduction of specific fears.

Another of the impact indicators analysed was the willingness to change, for which the participating patients were asked what changes they consider to implement as a result of having attended the mentoring group sessions. 65% of patients consider making a change in their life, compared to 35% who do not consider doing so. As for the changes they consider incorporating, the answers they gave were categorised into 5 categories: lifestyle in general (i.e.: changing my lifestyle), food (i.e.: adapting food), physical activity (i.e.: following the recommendations on physical activity), smoking (i.e.: trying to stop smoking) and coping (i.e.: adapting better to the future).

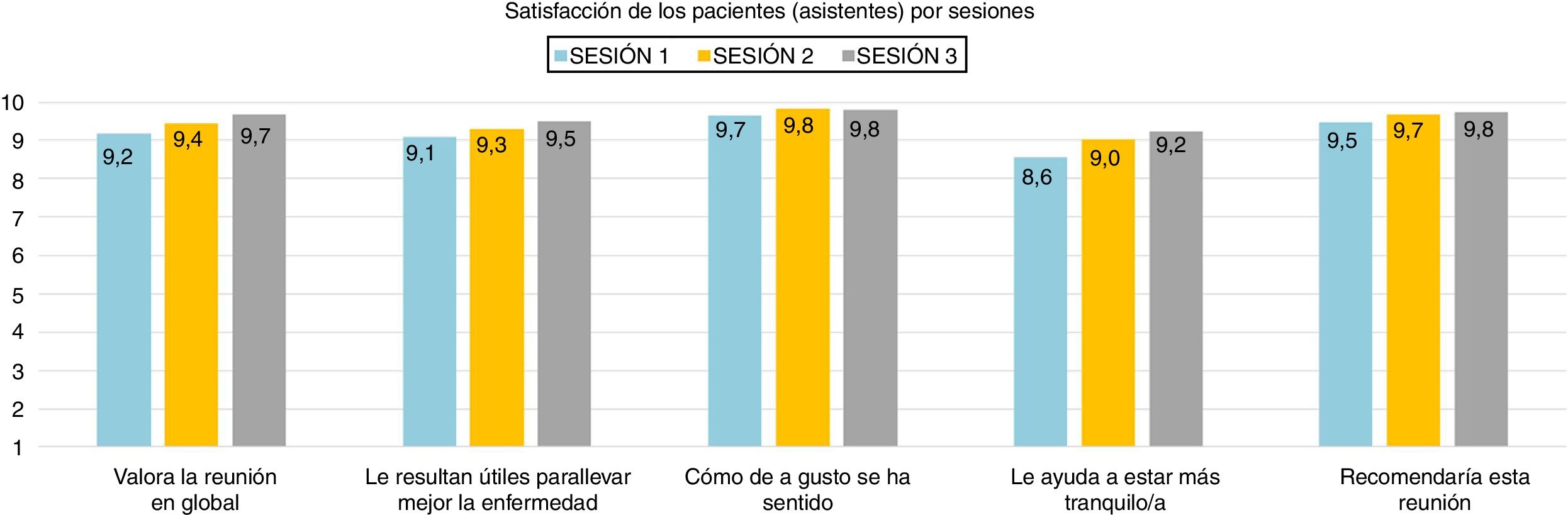

All items that assess satisfaction and utility have shown a very high score, above the value 8.5, very close to the maximum score of 10.

It should be noted that the item with the highest score in the 3 sessions was "How comfortable you felt", close in 3 sessions to the maximum value (Fig. 4).

POST mentors focus group resultsTwo focus groups were held, one in Madrid and one in Barcelona, and a total of 8 mentors participated.

Overall opinion of the mentoring program:

The group of mentors considers the mentoring program very positive; they see it necessary and useful because it addresses emotional aspects that are not usually addressed; they believe it is powerful because it is from patients for patients but, nonetheless, they consider it essential to give continuity in a medium-long term.

- •

M4: "It is a program that meets such an important need (referring to emotional aspects) and the physical aspect of kidney disease"

- •

M5: "I believe that it satisfies the patient's needs emotionally and mentally"

- •

M6: "For me it has been very good especially in the emotional sense because people were in the need of saying what they felt, of talking about their fears, of checking that theirs was the same as that of others and it was very good for everyone, and our meetings were very short"

- •

M7: "It is a support group of patients for patients and I think that is the strength of the program"

Changes and adjustments of the program to make it sustainable:

- •

Dissemination or publicity of patient support groups:

Mentors believe that dissemination or publicity is an aspect to be enhanced as they perceive that information about mutual help groups does not reach all patients.

- •

M4: "The issue of publicity, of reaching everyone, of having a marketing meeting, how to publicize everything so that all of us have access"

- •

Duration of the sessions:

Regarding the duration of the sessions, they unanimously consider that it is short.

- •

M6: "It is short, not possible in one hour, we were there up to 2 h"

- •

M4: "The sessions went well in an hour and a half, impossible in one hour"

- •

Increasing the number of sessions:

Along the same lines as the duration, mentors consider the number of sessions to be low (the program is designed with 3 sessions); they value increasing the number of sessions periodically over time.

- •

M6: "Three sessions is not enough, we want more"

- •

M7: "They are very few"

- ○

Ensure continuity of long-term programs:

- ○

The benefits of the program have been described and it is the mentors who call for a long-term continuity of this type of activity.

- •

M4: "If you make a huge effort, as you are making in the management of training, in managing mentors, to arrange patients, the doctors behind it, involves a superstructure that demands a lot of effort, why leave it with such little time?"

- ○

Constant support from health personnel:

- ○

According to the mentors' point of view, these types of programs are not viable if there is no ongoing collaboration with health professionals.

- •

M5: "Let the doctors explain to the patients that they should start in this and say: look, we have this type of workshop. Why don't you come in? It is a push that many patients need and I include myself"

- •

M4: "I think that total autonomy should not be given to the mentors, but there may be more autonomy, more independence with respect to the dynamics of each group, but always with the support of the healthcare professionals"

- •

M1: "All this starts with the doctor's involvement; he or she is the one who has to say: I am organising a group of this many people, and we (the mentors) go there"

In the case of health professionals, a focus group was held in Madrid in which a total of 10 professionals participated, with at least one representative from each centre attending.

Overall opinion of the mentoring program:

The group of health professionals considers the mentoring program very positive and satisfactory. Specifically they see it as:

- •

Necessary:

- ○

P1: "It has covered a gap that professionals cannot fill"

- ○

- •

Powerful:

- •

P4: "We have been surprised by the level of influence that peer work possesses. The level of credibility and trust they generate between them"

- •

- •

Conciliatory/shortening distances:

- •

P3. "It improves the relationship with the patients who have participated. We have identified the patients who have participated and there is a significant change in relationships with other patients and professionals. If they felt unheard, an distant, they have managed to overcome those limitations "

- •

- •

Complete:

- •

P1: "Because it benefits the patients who participate in the groups as well as the mentors themselves, who told us: I have reinvented myself as a person. It also helps us, professionals, because there is information received that sometimes from professional to patient, is hard to get"

- •

- •

Building support networks:

- •

P5: "In spite of having finished the sessions, there have been emails, telephone calls and when one of the mentored patients has been admitted they are called and they are given support. Networks have been made that you cannot reach"

- •

- •

Giving a leading role to the patient:

- •

P8: "The patient has been given a leading role he or she did not have. Both the mentor patient and the recipient have been given a leading role and a space they did not have"

- •

- •

It facilitates coping resources in a simple way:

- •

P3. "Patients are very decisive. With the issue of meals, for a person who was not going out for dinner because he or she felt he or she could not eat anything, a very simple rule was explained to them: If you are going out to eat meat or fish, in a certain amount and without sauce, thus you will never have a problem, and that helped you overcome the fear of eating out. They simplify it with something called experience"

- •

Changes and adjustments of the program to make it sustainable:

Homogenizing the type of patient to whom it is intended:

- •

Although the project is aimed at patients with CKD, some hospitals also included patients in other stages. This is an aspect to be assessed because expanding the type of patient to whom it is intended would facilitate more patients to benefit from the resource.

- ○

P2: "We have only worked with patients with CKD, but I think that in other places they have included transplanted patients, patients on dialysis, etc."

- ○

- •

Finding ways to reduce the difficulties involved in having chronic patient groups to reach agreements:

- •

P3. "The greatest difficulty is to get groups of people to agree: some have to go to work and cannot do it, others can only do it one day, others only in the morning, etc., you have to combine the schedules of many people and there are people who are very interested, but then they can never do it, etc."

- •

P2: "The problems that we have encountered at ACKD are that they have such a busy schedule of tests, that for them a session of talking with others is an overexertion, and they are already coming to the hospital too much to come back, etc."

- •

- •

Assigning a coordinator so that patients have a reference point within the care team:

- •

P5: "Patients told us that they needed a coordinator to call in case they cannot get there or have a problem. A point of contact apart from the mentors"

- •

- •

Expand the number of sessions over time:

- •

P1: "It is a shame not to take advantage of the networks that are generated among patients because there are some who ask you to follow up once a month, have more meeting times"

- •

P6: "An idea would be to keep the 3 sessions with closed groups and then continue with open sessions by themes every so often for open groups of patients who have already done the 3 sessions"

- •

- •

Material to disseminate the program among the care team:

- •

P8: "It would help to have some material for our partners because as we are starting, you plan to grow more, for example, make groups for the recently transplanted, etc."

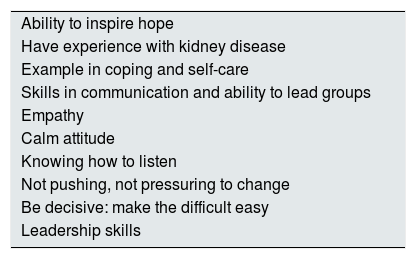

- •

Finally, it should be noted that a “Profile of the mentor patient” was developed in both focus groups independently (both with mentoring patients and with healthcare professionals) that, together with the research work of the group of psychologists of the program, has reached the consensus of the criteria to be taken into account for the detection of potential patients described in table 3.

DiscussionThe main finding of this study is that the implementation of a mentoring program in patients with CKD has been highly satisfactory for all the agents involved. Likewise, peer-to-peer emotional support needs have been made visible that will help us design possible future educational spaces in other phases of kidney disease (Table 2).

Mentor profile.

| Ability to inspire hope |

| Have experience with kidney disease |

| Example in coping and self-care |

| Skills in communication and ability to lead groups |

| Empathy |

| Calm attitude |

| Knowing how to listen |

| Not pushing, not pressuring to change |

| Be decisive: make the difficult easy |

| Leadership skills |

This is the first CKD mentoring program carried out simultaneously in 6 Spanish hospitals. The nature of the program, manualized and highly structured, allows it to be replicated, minimizing the risk of error.

The evaluation of the program has taken into account the perspective of the patients through a mixed methodology that includes two focus groups with the same being held. More and more authors remind us of the importance of considering the patient's perspective, since it allows clinicians to design programs around what is important for the patient.8

It is of great relevance that after attending the program 65% of patients consider making a change in their life, compared to 35% who do not consider doing so. This program shows results not only regarding satisfaction, by all the parties involved, but also of health promotion. These positive results for adjustment to the disease are in line with other peer-to-peer programs implemented in other types of chronic health conditions such as hypertension9 or epilepsy and the associated stigma.10

This project has allowed us to expand the experience of peer support as an educational tool in hospital teams.

This program is not without limitations. Due to ethical issues, and lack of resources, a control group was not implemented. Likewise, no follow-up measures have been carried out to study the stability of the changes achieved.

On the other hand, this type of program can have certain adverse effects in the short term that are related to the possible work overload of health professionals who coordinate the selection of mentors and logistics in each centre. Furthermore, there is a risk that not all selected mentors can finally end up "acting" as such. In our experience, only one mentor had to leave the program since during the training sessions the teacher detected that his coping with the disease was too rooted in the "fighting spirit".

In conclusion, the research team highlights the following:

The involvement and motivation that all participants have shown during the training sessions (expressing their points of view, expressing doubts and openly participating in the exercises that the teacher raised) is a clear indicator of success.

- •

The implementation of a patient-led mentoring program increases the sensitivity of professionals to the promotion of self-care and emotional support. The enormous satisfaction of the professionals involved is noteworthy.

- •

As for the participants, the high levels of satisfaction (mean = 9.4) reveals to us that both the mentor patients and the patients who attended the groups have found the activity very adequate.

- •

Attendees said that the program covered a need that is not usually met, which are the emotional aspects: the possibility of sharing with others their difficulties and venting their concerns has been highlighted as a great help in a disease involving such complex coping as this.

- •

Related to the above, some participants stated that they face the future with more optimism. This result alone, and what that means, makes incorporating such programs into daily clinical practice a challenge in the future.

- •

Attendees state that the number of sessions, and their duration, were not enough.

- •

An unexpected result, but very satisfactory, is that participation has brought professionals and patients closer, facilitating communication between them, making it more conciliatory and comprehensive (the latter was highly emphasized by professionals).

- •

Regarding the mentors, the vast majority have expressed their satisfaction for being able to help and the desire to repeat it.

- •

All the mentors highlighted the importance of this project and the help it can provide to people with CKD. They believe that it would have helped them to have had a resource of this type.

Taking into account that this was a pilot program, of which a guide aimed at professionals was created in order to replicate it,11 we would like to conclude that it is an action that enriches all those involved, and also provides effective and necessary help to patients with CKD by providing them with a space to share and learn to face a disease as challenging as the one they are facing.

Conflict of interestsThis study has been promoted and funded by Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal (VFMCRP). Vifor Group. VFMCRP has participated in this study in the design and implementation of logistical aspects along with the coordinating team. Gemma Oliveras has a financial interest as an employee of the company. The authors Dr H. García-Llana, Dr M.D. del Pino declare a conflict of interest having received fees as expert consultants on the advisory board of the study. All the authors reviewed the manuscript. The design, data collection, statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript were carried out by the Instituto ANTAE of Applied Psychology and Counselling Madrid, Spain.

Dr M. Auxiliadora Bajo Rubio. Nephrology Department. Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid; Dr Guillermina Barril Cuadrado. Nephrologist. Hospital Universitario de La Princesa. Madrid; Dr Fabiola Dapena. Head of the Neurology Department. Consorci Sanitari del Garraf. Barcelona; Dr Luis Miguel Lou Arnal. Nephrologist. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet. Zaragoza; Mrs Graciela Álvarez García Nurse Nephrology. Hospital Universitario de La Princesa. Madrid; Mrs Ana Castillo Plaza. Nurse Nephrology. Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid; Mrs Margarita María Martínez Lacueva. Nurse Nephrology. Consorci Sanitari del Garraf. Barcelona; Mrs Marta Quintela Martínez. Nurse. Dialysis care co-ordinator. Hospital Clínic. Barcelona; Mrs Maria Victoria Sánchez Castro. Nurse Nephrology. Complejo Hospitalario Torrecárdenas. Almería, and Mrs Filomena Trocoli González. Nurse. Supervisor Nephrology Department. Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid.

Los nombres de los componentes del Grupo de Trabajo de Mentoring en Nefrología están relacionados al final del trabajo.

Please cite this article as: García-Llana H, Serrano R, Oliveras G, Pino y Pino MD, Grupo de Trabajo de Mentoring en Nefrología. ¿Cómo diseñar, aplicar y evaluar un programa de Mentoring en enfermedad renal crónica? evaluación narrativa del impacto en 6 centros asistenciales. Nefrologia. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nefro.2019.04.002