Renal alterations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) worsen their prognosis and quality of life1 but, advances in last decades have fortunately allowed to better understand and treat acute kidney complications as well as those appear in the course of the disease. However, there is still a considerable number of resistant and recurrent episodes and very disturbing situations such as acute or subacute deterioration of renal function.2 In addition, because of the systemic nature of SLE, the nephrologists should expand their knowledge to extrarenal manifestations.

The Spanish Ministry of Health recently supported the development of a Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) for SLE management. The CPG is part of the Spanish Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment in the National Health System. Novel aspects in areas of uncertainty related to lupus nephritis (LN) and extrarenal manifestations in which nephrologists can be involved are summarized in the present editorial.3

MethodsThe methodology followed to develop this CPG for SLE patients is detailed in the original publication.3 The group conducted a process to identify and prioritize relevant topics to be addressed by the CPG, taking into account the relevant inputs from a Delphi consultation to people affected with SLE in Spain. Each selected clinical question were structured using the PICO format (Patients, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome). A systematic review of evidence was produced for each key question. The methodological quality of previous GPCs was assessed with the AGREE II instrument and included systematic reviews and individual studies were assessed based on the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria. The levels of evidence and grades of recommendations were also set according to SIGN criteria. For important practical aspects without scientific evidence available, good clinical practice recommendations (√) were formulated and agreed by consensus of experts. The expert group consisted of 10–13 professionals based on the nature of each recommendation (rheumatology, internal medicine, hematology, dermatology, immunology, nephrology, gynecology, neurology, nursing and hospital pharmacy) (Fig. 1).

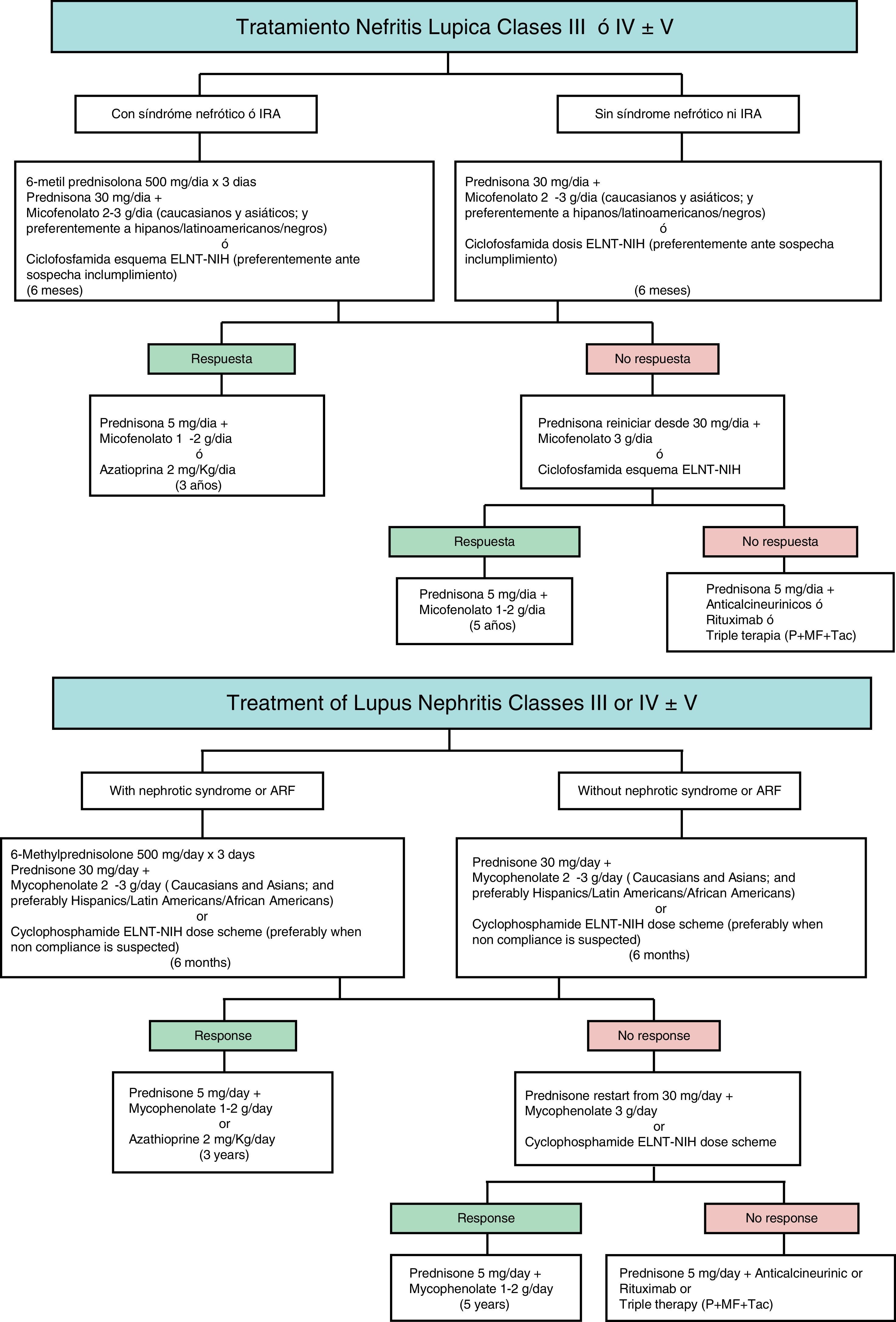

Therapeutic algorithm for severe lupus nephritis [classes III–V]. The choice of immunosuppressive agents should be adapted to the activity and chronicity indices of biopsy, clinical parameters at presentation, ethnicity and involvement of organs different from kidney. Abbreviations: ARF: acute renal failure. MF: mycophenolate. Tac: tacrolimus. P: prednisone. ELNT: Eurolupus Nephritis Trial. NIH: National Institute of Health.

This guideline addresses the following principal questions regarding LN:

Question n° 1. What dose of steroids would be more appropriate for the induction treatment? Under what conditions mycophenolate (MF) would provide advantages over other drugs?Summary of evidence:

- -

Methylprednisolone pulse therapy at a dose of 0.5–0.75g/day in three batches has shown similar effectiveness and fewer side effects than higher doses.4Level of evidence (LE) 3.

- -

Initial doses of prednisone not exceeding 30mg/day combined with hydroxychloroquine, immunosuppressants and/or methylprednisolone pulses lead to response rates at least similar to regimens with higher doses.5,6LE 1−/2+.

- -

The accumulated dose and the number of weeks with prednisone dose>5mg/day are associated with an increased toxicity.6LE 2+.

- -

Adverse effects of cyclophosphamide (CF) have led to the search for lower doses and alternative drugs with at least the same effectiveness. An accumulated dose of CF higher than 8g increases the risk of ovarian failure. For older patients, the safety dose is reduced up to approximately 5g.7LE 2+.

- -

For Hispanics/Latin Americans and African Americans, MF has shown to be more effective than CF.8LE 1+. For induction therapy, the most commonly used dose of mycophenolate mofetil (MFM) in high quality studies is 2g/day for mild to moderate NL in Europe and 3g/day for more severe ones in North America.9,10LE 2+.

Recommendations:

- -

Pulse therapy with methylprednisolone is suggested in the more severe cases, with nephrotic syndrome and/or renal failure. It's also suggested as oral prednisone saver. Grade of Recommendation (GR):√

- -

It is suggested to start with doses of oral prednisone not higher than 30mg/day. GR:C

- -

The decrease in prednisone dosages should be quick till ≤5mg/day. Reaching 5mg/day around 3 months and not later than 6 months is recommended. GR:C

- -

In women older than 30 years or at risk of ovarian failure, the use of low dose of cyclophosphamide (Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial [ELNT] pattern) or choose mycophenolate for both induction and maintenance treatment is suggested. GR:C

- -

In women of childbearing age who have received cyclophosphamide, reaching a cumulative dose higher than 8g (or 5g if older than 30 years), mycophenolate (or azathioprine) is suggested as first-line maintenance treatment in the current episode and as induction and maintenance treatment in successive episodes. GR:C

- -

If therapeutic non-compliance is suspected, cyclophosphamide instead of mycophenolate is suggested. GR:√

- -

In Hispanic patients from Latin America and African Americans, the administration of mycophenolate is suggested. GR:C

- -

The recommended dose of MFM in induction treatment is 2–3g/day or equivalent doses of sodium MF. GR:B

Summary of evidence: Overall, acute renal failure (ARF) is considered when an increment of serum creatinine >1.5-fold from baseline or an increment of 0.3mg/dl within 48h with or without oliguria is produced.11

- -

The incidence of ARF is probably low but unknown or undetermined since most large studies have excluded these patients. Only case studies, case series and retrospective cohorts are available. ARF is associated with worse prognosis for long-term renal survival.11,12LE 2+.

- -

The most common causes of ARF among people with NL, in addition to traditional ones in general population, are: extracapillary proliferation, necrotizing vasculitis (ANCA+), thrombotic microangiopathy and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. Authors who have described the presence of positive ANCAs in NL associated with necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis have used prednisolone and CF for induction treatment.13LE 2+.

- -

In patients with mild to moderate ARF (GRF<60ml/min/1.73m2), the MFM has shown to be as effective as in patients with normal GFR.14,15LE 2+.

- -

In a post hoc analysis of a clinical trial (CT), patients with GRF<30ml/min responded favorably and without differences between MFM and CF.16LE 2+.

- -

The treatment with CF was effective in patients with GFR between 25 and 80ml/min/1.73m2 although the recovery of renal function was limited at medium-term.17LE 1+.

- -

The pulse steroid therapy has been used in severe cases of NL with ARF. Doses of 500mg for three days may be sufficient.18LE 3.

Recommendations:

- -

The use of CF or MFM is suggested as induction immunosuppressive agent both in cases of mild to moderate IRA (GFR>30ml/min/1.73m2) and severe (GFR<30ml/min/1.73m2). GR:C

- -

Unless contraindication exists, the treatment with pulse steroid therapy is suggested in all cases of NL with ARF. GR:√

- -

In patients with NL and ARF with vasculitis/necrotizing glomerulonephritis injuries, the induction treatment with CF is suggested when ANCAs are positive. GR:D

Summary of evidence: Clinical trials and cohort studies in which the minimum duration of therapy was 24–36 months have shown that the incidence of renal flare in NL despite the immunosuppressive treatment is high, ranging from 12 to 45% in the first 2–5 years. From five years, the occurrence of renal flares would be progressively smaller and unusual after 10 years of remisión.19–22LE 1++/1+/2+.

- -

In proliferative LN, the occurrence of a renal flare is associated with a worse renal and patient survival.22 Nephritic type is associated with worse renal survival than nephrotic type.19,23–25 However, in the membranous class, renal flare does not seem to influence renal survival.25LE 2+.

- -

Extend the duration of maintenance treatment up to 30 months reduces the risk of early relapse and increases renal and patient survival.20,26 However, there are no clinical trials directly comparing longer or shorter treatment periods using the same therapeutic regimen. LE 1+/2+.

- -

The lupus nephritis activity is usually minimal in advanced stages of chronic renal failure over 12–24 months.22LE 3.

- -

Hydroxychloroquine therapy helps to maintain remission of LN and slows the progression of kidney failure.27LE 2+.

- -

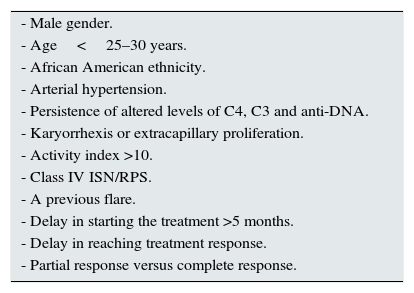

In patients with prolonged referral interval and without risk factors for recurrence (Table 1), it seems justified to consider the withdrawal of maintenance treatment.21,28LE 2+.

Table 1.Risk factors for renal recurrence described in different studies.21,25,27

- Male gender. - Age<25–30 years. - African American ethnicity. - Arterial hypertension. - Persistence of altered levels of C4, C3 and anti-DNA. - Karyorrhexis or extracapillary proliferation. - Activity index >10. - Class IV ISN/RPS. - A previous flare. - Delay in starting the treatment >5 months. - Delay in reaching treatment response. - Partial response versus complete response. - -

In patients at high risk of relapse (Table 1), an extension of the treatment for more than five years or even indefinitely is proposed unless it's contraindicated.29LE 4.

- -

Before considering treatment withdrawal, it seems justified to complete a minimum of 12 months of quiescence.21,28,30LE 2+.

- -

The termination of therapy must be very slowly.21,30 A close monitoring during the first five years, allowing early detection and treatment of renal flares, is associated to better long-term survival.23,31LE 2+.

Recommendations:

- -

Maintenance therapy is recommended for all patients who have achieved at least a partial response to induction. GR:A

- -

It is recommended to extend this maintenance therapy for at least 2–3 years. GR:B

- -

In patients with frequent recurrences without justifiable cause or risk factors for renal recurrence, it is suggested to extend maintenance therapy for at least five years. GR:√

- -

When considering the total withdrawal of immunosuppressive maintenance treatment, it should not be done before a period of clinical analytic quiescence shorter than 12 months. GR:C

- -

The total suspension of maintenance immunosuppressive therapy should be carried out slowly and progressively. GR:C

- -

Maintaining the long-term treatment with hydroxychloroquine is suggested, provided there are no contraindications or side effects for it. GR:C

Summary of evidence: There is no standard definition for refractoriness. However, considering the prognostic significance of not getting a reduction of baseline proteinuria of more than 50% at six months or a total proteinuria 1g/24h, the absence of at least partial remission after six months of treatment has been proposed as the main criterion of inefficiency. Refractoriness is therefore defined as the absence of at least partial remission after six months of treatment.32,33LE 4.

- -

Therapeutic non-compliance is one of the first reasons to be discarded before considering a treatment as ineffective. This risk should be discussed with patients in their first visits. A suspected non-compliance may be one of the reasons to assess drug levels or to choose in proliferative classes induction regimens with intravenous CF pulses.33,34LE 4.

- -

In refractory patients to standard immunosuppressive regimens (CF o MFM), tacrolimus monotherapy has been used with success and safety.35 Also in combination with MFM, in a multi-targeted approach that allows increasing overall immunosuppression with fewer individual doses.36,37LE 2−.

- -

In refractory patients to standard immunosuppressive regimens, the rituximab has been successfully used as rescue drug.38,39LE 2+.

- -

Several consensus CPGs, such as EULAR/ERAEDTA, eGEAS-SEMI/SEN and ACR,32,40,41 recommend using rituximab, calcineurin inhibitors, immunoglobulins or drug combinations in cases of refractory NL without satisfactory response to the change of the first-line treatment (MFM and CFM). LE GPC.

Recommendations:

- -

We suggest considering as refractory patients those who do not achieve remission at least partial after six months of treatment. GR:D

- -

As a first step for refractory LN, ensuring a proper therapeutic compliance and verifying that the renal lesions are reversible is suggested. GR:D

- -

In patients with LN refractory to cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate, the change to the other first-line drug (mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide) is suggested. GR:D

- -

The use of rituximab, calcineurin inhibitors or combinations of drugs is suggested in cases of unsatisfactory response to the change in first-line therapy (cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate). GR:D

Jaime Calvo Alen (Servicio de Reumatología, Hospital Sierrallana, Cantabria, España), María M. Trujillo-Martín (Fundación Canaria de INvestigación Sanitaria, La Laguna, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, España; Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas, Madrid, España), Iñigo Rúa-Figueroa Fernández de Larrinoa (Servicio de Reumatología, Hospital Universitario Gran Canarias Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, espala), Guillermo Ruíz-Irastorza (Unidad de Investigación de Enfermedades Autoinmunes, Servicio de Medicina Interna, Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Barakaldo, Vizcaya, España), Jose María Pego-Reinosa (Servicio de Reumatología Hospital Meoxoeiro, Vigo, España), Jose Maria Sabio Sanchez (Servicio de Medicina Interna, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, España), Pedro Serrano-Aguilar (Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas, Madrid, España; Servicio de Evaluación Planificación, Servicio Canario de Salud, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, España), Isidro Jarque Ramos (Servicio de Hematología, Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La F,e, Valencia), M. Teresa Martínez Ibáñez (Unidad Docente de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria, Gran Canaria, España), Pritti M. Melwani (Servicio de Dermatología, Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, España), Noemí Martínez López de Castro (Servicio de Farmacia Hospitalaria, Hospital Meixoeiro, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, Vigo, España), M. José Cuadrado Lozano (Servicio de Reumatología, Saint Thomas Hospital, Londres), Silvia García Díaz (Servicio de Reumatología, Hospital Moisés Broggi, Barcelona, España), Inmaculada Alarcón Torres (Servicio de Analisis Clínicos, Sección de Autoinmunidad, Hospital Universitario de Gran Canarias Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, España), Pilar Pazos Casal (Federación Española de Lupus, Galicia, España), Tasmania m del Pino-Sedeño (Fundaciń Canaria para el Avance de la Biomedicina y la Biotecnología, Islas Canarias, España).

Please cite this article as: Martín-Gómez MA, Rivera Hernández F, Frutos Sanz MA, Trujillo-martín MM. Recomendaciones y sugerencias a 4 preguntas clave en nefropatía lúpica: Extracto de la guía de práctica clínica 2015. Nefrologia. 2016;36:333–338.

![Therapeutic algorithm for severe lupus nephritis [classes III–V]. The choice of immunosuppressive agents should be adapted to the activity and chronicity indices of biopsy, clinical parameters at presentation, ethnicity and involvement of organs different from kidney. Abbreviations: ARF: acute renal failure. MF: mycophenolate. Tac: tacrolimus. P: prednisone. ELNT: Eurolupus Nephritis Trial. NIH: National Institute of Health. Therapeutic algorithm for severe lupus nephritis [classes III–V]. The choice of immunosuppressive agents should be adapted to the activity and chronicity indices of biopsy, clinical parameters at presentation, ethnicity and involvement of organs different from kidney. Abbreviations: ARF: acute renal failure. MF: mycophenolate. Tac: tacrolimus. P: prednisone. ELNT: Eurolupus Nephritis Trial. NIH: National Institute of Health.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/20132514/0000003600000004/v1_201612030031/S2013251416300918/v1_201612030031/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w94GCRvdQBB6xyQjMrWMzrts=)