To the Editor:

The genital oedema is a common complication in peritoneal dialysis that occurs due to the passing of dialysis fluid outside the abdominal cavity through inguinal hernias, persistent peritoneovaginal duct, lower abdominal wall defects, etc. Its association with persistent patent peritoneovaginal duct is widely described in literature1 but its relationship with polycystic kidney disease is not very well known. Below, we describe two cases of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) secondary to adult polycystic kidney and liver disease. After initiation of peritoneal dialysis, they developed fluid leakage to genitals, secondary to persistence of said patent duct.

CASE REPORT 1

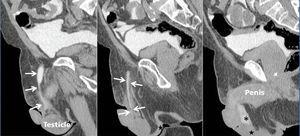

A 76-year-old male with stage 4 CKD secondary to polycystic kidney and liver disease with a long history of high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperuricaemia, dyslipidaemia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Given the situation of advanced CKD and after explaining the different dialysis techniques, a straight, non-self-locating 1 cuff peritoneal catheter was inserted by open surgery without immediate incidents, functioning well during the training period. A month after catheter placement, home continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) was started with a prescription of 3 exchanges of 2 litres of 1.5% dextrose, initially with neutral or negative balances of 200-300ml. After 4 days of treatment at home, he came to the Peritoneal Dialysis Unit complaining of genital oedema without other associated symptoms. Having performed a testicular ultrasound, pathology was ruled out at this level. On suspicion of leakage, CT peritoneography was carried out, after the administration of 100ml of hypoosmolar iodinated contrast (Optiray® 300mg/ml) by catheter, confirming the passage of peritoneal contrast material through the spermatic cord to the scrotum due to the presence of a non-dilated patent peritoneovaginal duct (Figure 1). Similarly, we observed the existence of a left ipsilateral indirect inguinal hernia with a sac up to 58mm in diameter (Figure 2). Given these findings, peritoneal rest is decided and surgery is indicated for correction of inguinal hernia and closure of the peritoneovaginal duct. With these measures, and after restarting low-volume peritoneal dialysis, no leakage was observed a month after reintervention.

CASE REPORT 2

A 45-year-old male with stage 5 CKD secondary to polycystic kidney liver disease with a history of high blood pressure and hyperuricaemia. Given the progressive deterioration of renal function requiring renal replacement therapy, and after explaining the different techniques, a straight, non-self-locating, 1 cuff peritoneal catheter is inserted. A month after starting CAPD at home with 4 exchanges of 2 litres of 1.36% glucose, the patient came to the Peritoneal Dialysis Unit complaining of inguinoscrotal oedema lasting 48 hours. After discarding orchiepididymitis, CT peritoneography was performed as in the previous case, confirming the passage of contrast to the testicles through a patent peritoneovaginal duct. Peritoneal rest was decided and the patient was transferred to haemodialysis. A month later, surgical closure of the peritoneovaginal duct was carried out and CAPD restarted in June 2009 without incident or recurrence of the leakage.

DISCUSSION

Patients on peritoneal dialysis have an increased risk of both incisional and inguinal hernias. This is especially true in certain risk populations (multiparous women, the elderly and children).2,3 These hernias induce peritoneal fluid leakage, with one of the most common clinical manifestations being scrotal oedema.4,5 There are, however, other causes of peritoneal fluid leakage which produce scrotal oedema but which must also be taken into account, such as patent peritoneovaginal duct. The peritoneovaginal duct is patent in 90% of infants at birth, but it closes in the first year of life, and as such, only about 15% of adult men have a patent duct, which is generally asymptomatic. In children, the incidence of indirect inguinal hernia due to a patent peritoneovaginal duct seems to be higher. In fact, peritoneography has been suggested during the insertion of the catheter for the closure of the deep inguinal ring, in the event of peritoneovaginal duct persistence.6 Although not widely reported in literature, it seems to be that, as in the cases we reported, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is associated with a greater presence of patent peritoneovaginal duct. It is for this reason that, with the appearance of scrotal oedema in patients on peritoneal dialysis for adult polycystic kidney liver disease, we must suspect and confirm the presence of patent peritoneovaginal duct by CT peritoneography or scintography. Also, in this patient population, it would be advisable to consider prior peritoneography in order that, if there is patent peritoneovaginal duct, it will be closed directly, thereby preventing leakage and its potential closure in a second operation as well as the carrying out of radiating tests for its diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. CT peritoneography

Figure 2. CT peritoneography