Dear Editor,

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is characterised by the presence of nephrotic syndrome, hypertension and progressive deterioration of kidney function. Although in many cases its aetiology is unknown, it has been associated with inherited disorders, viral infections, induced by toxic substances and with hyperfiltration situations.1

Polycythaemia vera (PV) is a myeloproliferative disorder of unknown aetiology characterised by excessive production of normal erythrocytes, leukocytes and platelets.2

Glomerular involvement in PV is rare. We present a patient diagnosed with PV with nephrotic syndrome secondary to GSF and progressive kidney disease.

An 83 year-old woman, diagnosed with PV 4 years earlier, was admitted for the study of nephrotic syndrome and kidney disease of 2 years evolution.

There was no family history of polycythaemia. Among her background was: left nephrectomy due to hypernephroma at 63 years, bronchiectasis with recurrent bacterial superinfections, hypertension controlled with medication and celiac disease well controlled through diet. Four years earlier she was diagnosed with PV after a bone marrow biopsy, including details of polycythaemia and thrombocytosis, well controlled with hydroxyurea treatment (500mg/day).

In March 2007, she began with nephrotic range proteinuria (4.2g/day) with Crs 1.1mg/dL; antiproteinuric treatment was started with telmisartan 80mg/day and spironolactone 50mg/day. A month later the proteinuria dropped to 1.2g/day with no change in the creatinine. She was admitted to hospital in June 2007 for severe hyponatraemia (107mEq/L), symptomatic, with hyperkalaemia (5.7mEq/L) and metabolic acidosis (pH 7.34) secondary to treatment with spironolactone. Due to the persistence of nephrotic proteinuria and her history of bronchiectasis, a biopsy of rectal and abdominal fat was performed which discarded the existence of amyloidosis. Throughout its evolution, the proteinuria varied between 4-10g/day and started with lower limb oedema, decreased total protein and albumin (5.4/2.7g/dL) and a progressive decline in the glomerular filtration rate (Crs 1.6-1.7mg/dL).

In May 2009 she was admitted to hospital due to a deterioration in her general condition, oedema, Crs 3.6mg/dL and proteinuria 8.4g/day despite treatment with ARB. On admission, her blood pressure was 137/82mmHg; in the physical examination her systolic ejection murmur was heard II/VI in the left sternal border, and she had bilateral pitting oedema up to the root of her thigh. CBC: haemoglobin 16.8g/dL, haematocrit 56%, RBC 6,750,000/µL, 11,690/µl leukocytes with normal formula and platelets 460,000/µl. Crs 4.3, urea 102 (mg/dL). Total protein 5.9, albumin 2.5g/dL, cholesterol 188, triglycerides 260, uric acid 9.8mg/dL. Proteinuria 6.9g/d; 1.4 sediment erythrocytes/field and 5-10 leukocytes/field. Immunology: ANA, anti-DNA, ENA, ANCA and anti-GBM negative. Complement: C3 79, C4 30mg/dL. CRP 0.37mg/dL. Rheumatoid factor negative. IgG 820, IgA 185, IgM 188mg/dL. Kappa 635, lambda 515mg/dL. Kidney biopsy was performed with 8 glomeruli of which two were completely sclerosed, and the remaining six, one global mesangial expansion with increased mesangial cells could be seen and the other five had segmental proliferative lesions without necrosis accompanied by moderate epithelial proliferation. The interstitium showed moderate fibrosis with tubular atrophy and occasional chronic inflammatory infiltrates. Arterial and arteriolar vessels with hyperplastic lesions with occasional hyaline lesions. These findings were indicative of cellular variant segmental proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Treatment was initiated with three shocks of 125mg of 6-methylprednisolone followed by prednisone (1mg/kg/day) and mycophenolate mofetil (360mg/12 hours). No evidence of a decrease in proteinuria was seen and kidney function deteriorated progressively with clinical uraemia. So it was decided to make the right jugular catheter permanent and initiate treatment with periodic haemodialysis. A progressive improvement in the symptoms was seen. Treatment with mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued and prednisone was gradually withdrawn.

The patient developed a nephrotic syndrome secondary to FSGS 4 years after detection of the polycythaemia. It met the WHO criteria for diagnosis of PV2 (Hb greater than 16.5g/dL in women, no cases of secondary polycythaemia, decreased EPO levels, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis > 400,000/µl and leukocytosis > 12,000/µL). Despite good control of the PV with hydroxyurea and treatment with high dose steroids and immunosuppressive agents, the nephrotic syndrome did not improve, and was accompanied by a progressive deterioration of kidney function with uremic symptoms and initiation of replacement therapy.

The kidney biopsy showed the existence of a focal segmental glomerulosclerosis cell variant that had a worse prognosis than the other FSGS (perihilar hyalinosis, tip variant and classical variant) and better than collapsing variant.3

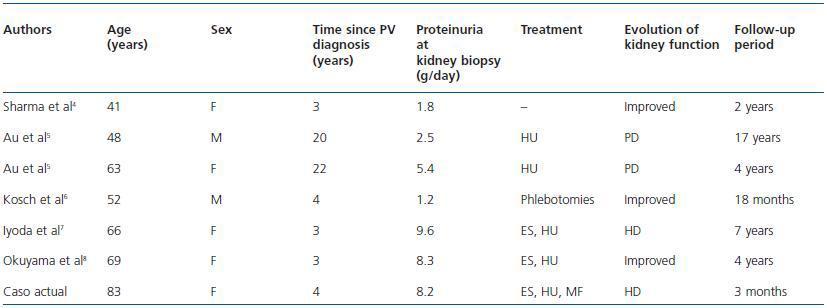

The joint presence of FSGS and PV is a rare combination. There have only been 6 published cases confirmed histologically in the literature.4-8 Table 1 summarises the clinical data of the 6 cases reported and of the current one.

From this we can get some interesting data. The average age at the time of kidney biopsy was 60.3 years (range 41-83). FSGS was diagnosed up to 4 years after the detection of polycythaemia in 5 of the 7 cases (71.4%). Four patients (57.1%) developed nephrotic range proteinuria, 3 patients were treated with steroids and immunosuppressive agents, of whom only one had improvement of kidney function. The other two were given haemodialysis due to progressive deterioration of plasma creatinine with onset or worsening of uremic symptoms.

The presence of FSGS in these patients could be directly related to the PV. As noted by Sharma et al,4 the haemodynamic changes in the PV, as well as kidney vasodilation and increased effective kidney blood flow could trigger kidney glomerulosclerosis. Ferrario et al9 suggested that the haemodynamic glomerular injury induces the activation of the mesangial cells, leading to overproduction of extracellular matrix. Furthermore, damaged endothelial cells facilitate platelet activation by releasing platelet activating factor, which induces proliferation of endothelial and mesangial cells. These alterations may contribute to the development of glomerular sclerotic changes.

To summarise, we recommend regular testing for the presence of kidney damage in patients with PV. Ifthese patients develop proteinuria, association with FSGS could be considered as a possible complication, although it is rare. The combination of steroids and immunosuppressive drugs administered early in patients with nephrotic range proteinuria may slow the progression of kidney damage.

Table 1. GSF cases associated with PV