Nosocomial infections are potentially preventable conditions, with a high socioeconomic cost.1 Vascular access for haemodialysis is constantly subjected to manipulation by health personnel, so in these patients the risk of bloodstream infections increases considerably.2

Achromobacter is a non-fermentative, gram-negative aerobic bacillus of the Burkholderiales order, widely distributed in nature.3 It has been obtained from various types of environmental samples from surfaces in hospital units.4 In the context of haemodialysis patients, few cases of infection by this microorganism have been described.5,6 It has been identified in outbreaks in other patient cohorts, and is often associated with medical care or the use of antiseptic solutions.7–10 To date, there have been no epidemic outbreaks associated with this bacterium in any type of patient in Mexico.

We present an outbreak of bacteraemia caused by two species of Achromobacter in haemodialysis patients at a hospital in Guadalajara, Mexico. The objective was to identify the source of infection to establish measures for its control and to characterise the clinical charactreristics of these cases.

The outbreak study was developed between April and July 2019, and all patients assigned to the Haemodialysis Unit (HU) of the hospital were included. Suspected cases were patients who received haemodialysis sessions in the HU during that period and who had a fever or chills after a session. A blood sample was taken from all of them for blood culture.

To identify the source of contagion among the patients, samples were collected from surfaces with potential risk of contamination: sinks, haemodialysis machines and chairs, and antiseptic solutions from the catheter insertion site.

Of the 207 patients assigned to the HU, 34 (16%) presented with symptoms compatible with bacteraemia. In 17 of these patients, the diagnosis of Achromobacter bacteraemia was confirmed, in 10 cases (59%) Achromobacter xylosoxidans was isolated, and in seven (41%) Achromobacter denitrificans was isolated.

All confirmed cases presented chills during the sessions, but in the telephone interview they reported having presented other signs and symptoms. These included fever in six of the cases (35%), tachycardia in 12 (71%), hypotension in four (24%), and tachypnoea in one (6%).

It should be noted that all the cases had a temporary catheter for haemodialysis, and 16 of them (94%) had it for more than six months. The main clinical and demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Main clinical and biochemical characteristics of the cases of bacteraemia due to Achromobacter spp.

| Variable | Cases of bacteraemia due to Achromobacter spp. |

|---|---|

| N | 17 |

| Gender, male/female | 8/9 |

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 52 ± 18 |

| Vascular access, temporary catheter/arteriovenous fistula | 17/0 |

| Months since the placement of the vascular access | 31 ± 33 |

| Temporary catheter for more than 6 months (%) | 16 (94) |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 9 (53) |

| Haemoglobin, g/dl (mean ± SD) | 9 ± 2 |

| Leukocytes, 103/l (mean ± SD) | 7 ± 3 |

| Leukocytosis (%) | 3 (18) |

| Leukopenia (%) | 3 (18) |

| Platelets, 103/l (mean ± SD) | 203 ± 74 |

| Lymphocytes, 104/μl (mean ± SD) | 1 ± 0.6 |

| Monocytes, 104/μl (mean ± SD) | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| Eosinophils, 104/μl (mean ± SD) | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| Neutrophils, 104/μl (mean ± SD) | 5 ± 0.3 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl (mean ± SD) | 9 ± 4 |

| Glucose, mg/dl (mean ± SD) | 102 ± 65.6 |

| Urea, mg/dl (mean ± SD) | 96 ± 50.8 |

SD: standard deviation.

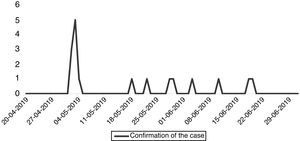

On 5 May, the HU reported to the Epidemiological Surveillance Unit (USE) the presence of several apparently associated cases of bacteraemia. The microbiology laboratory (ML) reported the presence of a previously unreported microorganism on the same day. On 15 May, the USE integrated this information and declared the presence of the outbreak in the HU with nine confirmed cases, for which vigilance of hand hygiene measures was intensified and exhaustive cleaning routines were carried out to contain the outbreak without suspending activities. Fig. 1 shows the epidemic curve, according to the date of confirmation of the cases.

The results of the environmental bacteriological sampling reported the presence of Achromobacter xylosoxidans and Achromobacter denitrificans in the benzalkonium chloride disinfectant solution used, obtained from the bottles used in the haemodialysis area, and in unopened containers from one of the product batches that were found in the unit's warehouse, and the suspension of its use was ordered. In the cultures of the surface samples and other solutions, no growth of any organisms was observed.

The confirmed cases were exclusively concentrated in the haemodialysis area, because the disinfectant solution was used only in this service.

After the withdrawal of the disinfectant solution from the hospital, there were no more cases. The last case was identified on 18 June and the incident was deemed ended on 1 July.

In all cases, the infection was resolved. However, nine patients (53%) were hospitalised to continue with the bacteraemia study protocol, and in three of them the catheter was removed and repositioned the same day. All patients survived the infection and continued with renal replacement therapy without complications.

It was concluded that the benzalkonium chloride solution, contaminated at origin, was responsible for the outbreak. In 2015, this solution from the same brand was associated with an outbreak of Serratia marcescens in another HU of a hospital in the same city.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Vázquez Castellanos JL, Copado Villagrana ED, Torres Mendoza BMG, Gallegos Durazo DL, González Plascencia J, Mejía-Zárate AK. Primer brote de bacteriemia por Achromobacter spp. en pacientes de hemodiálisis en México. Nefrologia. 2022;42:101–103.