In the field of solid organ transplantation (SOT), the xtracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) is a type of apheresis which is indicated in the treatment of lung, heart and liver rejection.1,2 Debate continues over its usefulness in renal transplantation (RT) due to the lack of studies on the safety and effectiveness of the technique.3–5

ECP is an immunomodulatory therapy, combining leukapheresis with phototherapy in the treatment of leucocytes with 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP) and ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation.2 It consists of three phases6: (1) collection, by separating the mononuclear cells from the rest of the components of the blood by means of centrifugation; (2) photoactivation, by adding 8-MOP and subsequent radiation with UVA; and (3) re-infusion of the photoactivated material into the patient.

The mechanism of action of ECP is not fully understood, and different pathways have been suggested7,8: (1) after inducing apoptosis of lymphocytes and being re-infused, they are recognised by dendritic cells (DC) whose interaction inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines and promotes anti-inflammatory factors7; (2) monocytes activated in the extracorporeal system and re-infused are differentiated into immature DC capable of capturing peptides released by the alloimmune T lymphocyte and triggering a clone-specific cytotoxic response against it8; and (3) it induces the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), with a key role in immune tolerance.8

We present the following retrospective descriptive study with our initial experience of ECP in RT. We included all RT patients from our centre with histological diagnosis of graft rejection who had been treated with ECP from 2013 to 2018, in order to describe the demographic and clinical variables and their outcomes.

During the study period, a total of eight patients were treated. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. In terms of treatment, the indication for ECP was contraindication to conventional therapy (n = 4), mainly due to concomitant infection (50%), or being refractory (n = 4) to the treatment prescribed in each case (see Table 1). The initial regimen was two consecutive sessions a week for five weeks, with additional sessions depending on the progress on completing the first round. The majority of the patients were able to finish the scheduled sessions (n = 5). The three reasons for discontinuation were lack of treatment response, hospital admission and arteriovenous fistula (AVF) thrombosis.

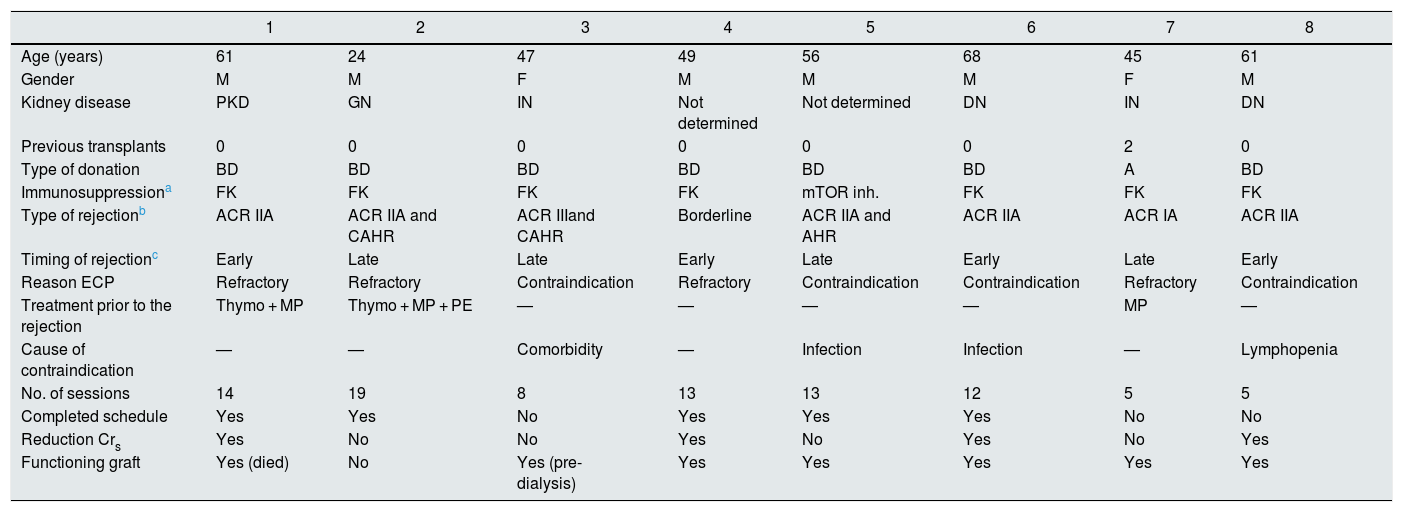

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with kidney graft rejection treated with ECP.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 | 24 | 47 | 49 | 56 | 68 | 45 | 61 |

| Gender | M | M | F | M | M | M | F | M |

| Kidney disease | PKD | GN | IN | Not determined | Not determined | DN | IN | DN |

| Previous transplants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Type of donation | BD | BD | BD | BD | BD | BD | A | BD |

| Immunosuppressiona | FK | FK | FK | FK | mTOR inh. | FK | FK | FK |

| Type of rejectionb | ACR IIA | ACR IIA and CAHR | ACR IIIand CAHR | Borderline | ACR IIA and AHR | ACR IIA | ACR IA | ACR IIA |

| Timing of rejectionc | Early | Late | Late | Early | Late | Early | Late | Early |

| Reason ECP | Refractory | Refractory | Contraindication | Refractory | Contraindication | Contraindication | Refractory | Contraindication |

| Treatment prior to the rejection | Thymo + MP | Thymo + MP + PE | — | — | — | — | MP | — |

| Cause of contraindication | — | — | Comorbidity | — | Infection | Infection | — | Lymphopenia |

| No. of sessions | 14 | 19 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 5 | 5 |

| Completed schedule | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Reduction Crs | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Functioning graft | Yes (died) | No | Yes (pre-dialysis) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

A: asystole; ACR: acute cellular rejection; AHR: acute humoral rejection; BD: brain dead; CAHR: chronic active humoral rejection; Crs: serum creatinine; DN: diabetic nephropathy; ECP: extracorporeal photopheresis; F: female; FK: tacrolimus; GN: glomerulonephritis; IN: interstitial nephropathy; M: male; MP: methylprednisolone; mTOR inh.: mTOR inhibitor; PE: plasma exchange; PKD: polycystic kidney disease; Thymo: thymoglobulin.

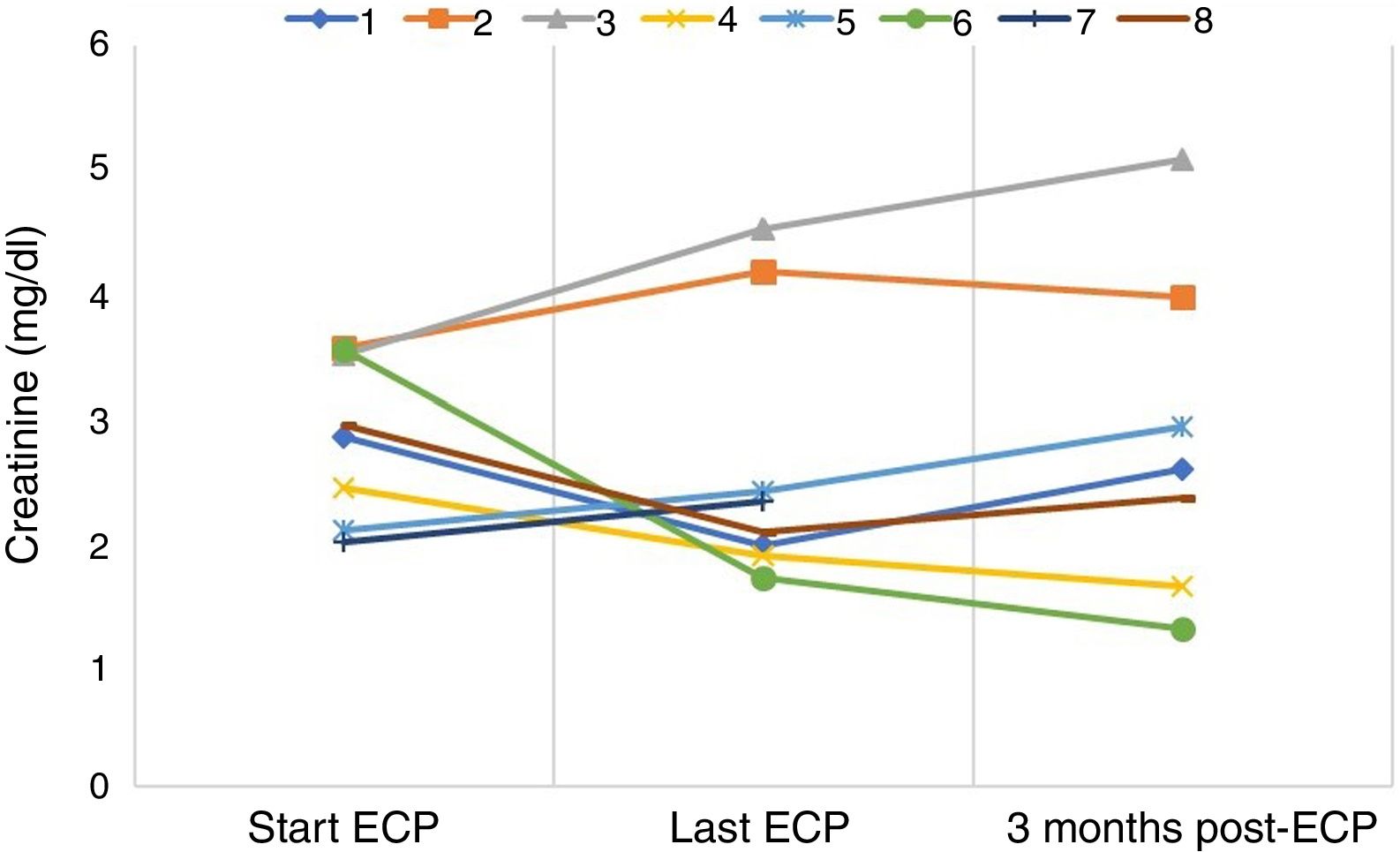

As regards clinical results (Table 1), improvement in graft function in terms of creatinine reduction at the end of therapy (Fig. 1) was found in patients with early acute cellular rejection (ACR) (n = 4) and was sustained three months after finishing treatment. The only late ACR (>3 months post-transplant) was unable to complete the initial regimen. None of the grafts with a humoral component showed improvement in renal function. One patient with chronic active humoral rejection (CAHR) suffered loss of the graft and had to restart dialysis. The other patient with CAHR is in a pre-dialysis situation.

From a technical point of view, a total of 89 procedures were studied, all performed with the THERAKOS® CELLEX® Photopheresis System, with the administration of methoxsalen solution (UVADEX®) and photoactivation with ultraviolet A light. Vascular access per session was AVF (76%) or central venous catheter (CVC) (24%); peripheral access was not used in any of the cases. Each procedure lasted an average of 112.72 ± 13.85 min (range: 86–145). The treatment volume ("buffy coat") was 189.11 ± 28.67 ml per session, and the total volume of fluids administered (NaCl and anticoagulation) was 559.40 ± 41.17 ml.

From a safety perspective, the complications observed during the sessions were fever/low-grade fever (n = 2), thrombosis of the AVF (n = 1), clotting of the extracorporeal system (n = 1) and anaemia (n = 1). Inter-procedurally, there was one case of urinary infection which required hospital admission and discontinuation of therapy. One patient died of cardiovascular disease four years after the therapy with a functioning graft.

From our experience, although limited by the type of study and the lack of a control group, we are able to draw three initial conclusions:

- 1

The utility of ECP seems to be in cases of cellular rejection, probably related to the triggering of a immunomodulatory response of the lymphocytes.

- 2

There is no established treatment regimen in RT, although previous series have shown that regimens with a frequency greater than monthly obtain better results.9

- 3

It can be considered a safe, well tolerated treatment. In our experience, there are few intra-session complications (5 in 89 procedures), and according to the literature, there is no increase in the incidence of infections or malignant tumours.10

Lastly, we would like to highlight two aspects particular to RT patients: on the one hand, being renal patients means the majority have AVF as vascular access, with a lower risk of infection in relation to the technique, unlike patients with non-renal transplants who need to have a CVC for access; while on the other, although no complications due to volume overload have been described, we consider that special care should be taken with patients who require fluid restriction (infusion of 560 ml on average per session).

In conclusion, more studies are needed with a larger number of patients and a control group to be able to confirm the effectiveness and safety of ECP in RT, and to be able to consider it a useful therapeutic tool, as in other SOTs.

Please cite this article as: Fernández Granados S, Fernández Tagarro E, Ramírez Puga A et al. Fotoféresis extracorpórea y trasplante renal. Nefrologia. 2020;40:687–689.