Renin-angiotensin system inhibition is a commonly used therapeutic measure for slowing the progression of kidney disease in diabetic nephropathy and nephropathies with proteinuria. It has also been established that activation of this system is necessary for maintaining glomerular filtration when renal perfusion is severely impaired, as occurs in ischaemic nephropathy and cases of hypotension and dehydration. In these situations, the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) can deteriorate renal function.

In a recent and very shocking study carried out in patients with advanced chronic renal failure, Ahmed et al showed that halting renin-angiotensin system inhibitor treatment was associated with a relevant and persistent improvement in renal function, with an increase in glomerular filtration rate >25% in 61.5% of cases.1 These results led us to question the adequacy of using these drugs in advanced chronic kidney disease, and we decided to confirm these findings in our own patients.

Between January and June 2011, ACE inhibitors and ARBs were suspended in patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease that were undergoing predialysis programmes at the Hospital Ramón y Cajal Hospital in Madrid. The study included a total of 14 patients (5 women and 9 men) with a mean age of 68±12 years (range: 42-88 years). The aetiologies of the different cases were diabetic nephropathy (5 cases), nephroangiosclerosis (3 cases) polycystic kidney disease (2 cases), and other (4 cases). Eleven patients were receiving ARBs, one received ACE inhibitors, and the other two received both ARBs and ACE inhibitors. These drugs were replaced with calcium channel blockers or beta blockers. When the renin-angiotensin system inhibitor was suspended, all patients were clinically stable, with no signs or symptoms of heart failure, with blood pressure values under control and fractional sodium excretion ranging between 2% and 5.6%.

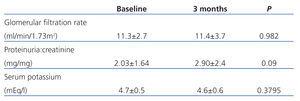

Table 1 summarises the progression of glomerular filtration rate (MDRD-4), proteinuria (proteinuria:creatinine ratio) and serum potassium concentration since the renin-angiotensin system inhibitors were suspended (baseline values) to three months later.

We only observed an increase in glomerular filtration rate >25% in one patient, and this increase was temporary. Overall, the removal of ACE inhibitor and ARB treatment was associated with an almost statistically significant increase in proteinuria. However, in 5 patients, the increase in proteinuria:creatinine ratio in urine samples was greater than 1mg/mg. There were no changes in serum potassium concentrations. We did not found an increase in blood pressure in any patient following the suspension of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors; however, two patients requested reinstatement of treatment, attesting to a better clinical tolerance. No patients suffered cardiovascular events during the follow-up period.

Our results in patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease differ from those published by Ahmed et al. Although these drugs may worsen renal function in cases of compromised renal perfusion, the removal of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors failed to provide any relevant benefits in clinically stable patients without signs of dehydration. Even in these advanced phases of renal failure, ACE inhibitors and ARBs have an antiproteinuric effect. We believe that larger studies are needed in order to clarify whether suspending treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs in advanced chronic kidney disease impacts glomerular filtration rate, and if so, which patients would benefit from this protocol.

Conflicts of interest

The authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Table 1. Evolution of glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria following suspension of ACE inhibitors and ARBs