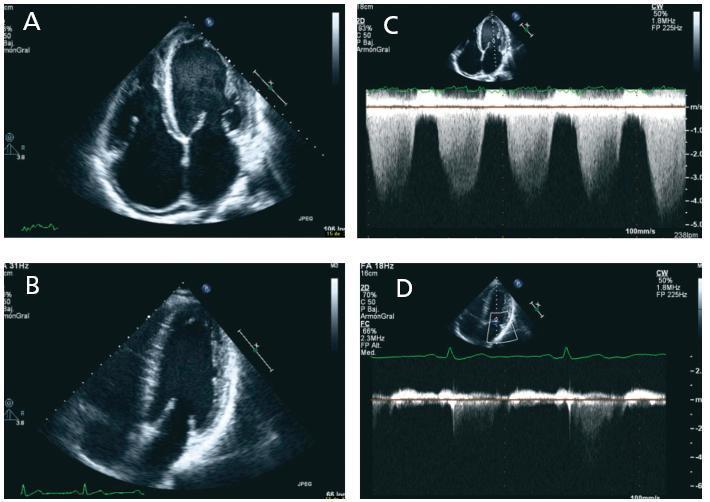

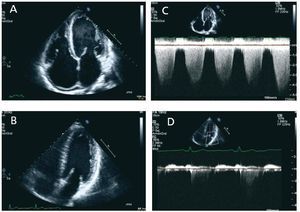

Dear Editor, We present the case of a 36 year old man with chronic renal failure and hypertension secondary to nonbiopsied chronic glomerulonephritis. An arteriovenous fistula (AVF) was created, and six months later in August 2007, the patient had to begin replacement therapy by haemodialysis. The echocardiogram (ECG) taken on 22 August 2007 did not show findings with pathological significance (mild left ventricular hypertrophy, absence of valvular abnormalities, valvular competence and good systolic function with a stress test that was negative for ischaemia). Six months after starting dialysis he began to experience progressive dyspnoea, pressure on the chest and poor tolerance for dialysis, so he was changed to daily haemodialysis. He underwent additional testing including another ECG in February 2008, which showed a systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle (visual ejection fraction [EF] 40%, telediastolic volume [TDV] 157mm, telesystolic volume [TSV] 105mm, a slight dilation of the left atrium with mild to moderate mitral regurgitation and severe pulmonary hypertension. New ECGs were repeated in August and September 2008, and we observed a decrease of up to 25% in systolic function, loss of ventricular configuration with enddiastolic volume increasing to 185ml, severe functional mitral regurgitation with increased atrial dilation and increase in the degree of pulmonary hypertension (figure 1). In November 2008, the patient underwent a kidney transplant with a good recovery, and creatinine level at the time of discharge was 1.5mg/dl. It was decided to close the AVF during the postoperative period. In the months following the transplant the patient remained asymptomatic and the ECG parameters measured in July 2009 are better: mitral regurgitation has disappeared completely, EDV is 129ml and the EF is 45% (figure 1). Congestive heart failure is 12 to 36 times more frequent in patients on dialysis than in the general population. Proper treatment is a topic for debate. It is not clear whether or not the general recommendations for treating heart failure in the general population are equally effective and safe in the population on dialysis. Furthermore, this patient group is at high surgical risk. The lack of evidence on the effect of transplants on perioperative morbidity and mortality means that these patients are often not evaluated for transplant, and when they are, it is often not clear whether or not they should be included on the waiting list. Wali et al.1 evaluated the impact of transplant on 103 patients with chronic heart failure and an EF of less than 40%, and they saw a clear improvement 12 months after the transplant, even in patients whose heart function was affected the most. Kidney transplant should be considered in patients with heart failure, since remaining on dialysis may result in progressive, irreversible myocardial dysfunction. Other studies also indicate that kidney transplant, with all of the physiological changes that it entails and the way it corrects factors arising from uraemia, can decrease and often resolve cardiac abnormalities secondary to chronic renal failure. It reduces hypertrophy and dilation of the left ventricle and improves systolic and diastolic ventricular function.2-4 Therefore, the notable improvement in cardiac function after a kidney transplant reinforces the indication of transplants in these patients.

Figure 1. Two-dimensional echo (A and B), apical two-chamber view, showing the evolution of the different cavities in size and volume. In the Doppler images below (C and D), we observe that mitral regurgitation practically disappears after the kidney transplant is