To the Editor,

Haemodialysis patients are more likely to develop infections due to changes in their immune response associated with kidney failure. The use of some immunosuppressor drugs and pathologies such as diabetes also make infections more likely.1-4 In recent years we have witnessed an increase in the incidence of tuberculosis (TB) in the general population, and as a result in the haemodialysis population as well.1 The diagnosis of TB in these patients is hindered by its insidious and unspecific medicial symptoms. Also, some diagnostic tests and screening fail to identify the disease in this group of patients.3,5

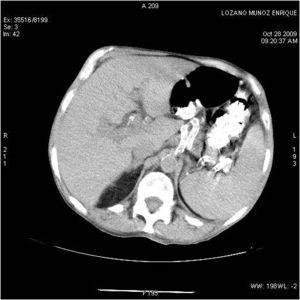

We present the case of a 67-year-old male patient in a haemodialysis program with a history of high blood pressure, a positive blood test for hepatitis C virus, and chronic kidney disease due to nephroangiosclerosis. He began haemodialysis in 1989, had a kidney transplant in 1990; he has post-transplant diabetes mellitus; he began dialysis again in September, 2007. He has been in treatment for 3 months with prednisone at 30 mg/day due to an initial clinical suspicion of kidney graft rejection. He was admitted with week-long fever and night sweats without apparent source. The case history of the patient and physical examination were not specific, only revealing asthenia and weight loss in the last few months. Blood, urine, pleural liquid and sputum cultures were negative, as were x-rays of the chest and abdomen. He began broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. The study was continued to find the source of the fever. The results of transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography were normal. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from only one of the subsequent blood cultures, so the antibiotic treatment was changed and transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiograms were performed again. These ruled out endocarditis. In view of the persistent fever, antifungal treatment was added. Tests revealed: PCR 13 U, total protein 5.1 g/dl, albumin 2.3 g/dl, leukocytes 3600 mm3 (80% neutrophils), Hgb 12.4, hematocrits 37%, platelets 102 000 x 10.9 Abdominal ultrasound showed splenomegaly with multiple small, well-defined hypoechoic areas of up to 1cm in diameter which could correspond to multiple splenic microabscesses. The patient underwent a thoracoabdominal CT scan which showed multiple mediastinal lymphadenopathies of up to 2cm in diameter in the retrocaval-pretracheal, para-aortic, upper and lower right paratracheal, and subcarinal spaces. Bilateral pericardial and pleural effusion. Mosaic attenuation of lung parenchyma. CT scan showed at least 3 pseudonodular focal masses of around 1cm in diameter in a peripheral, subpleural location in an anterior segment of the right upper lobe, and 2 masses in the left upper lobe. Irregular interstitial and acinar infiltrates at the base of the abdomen and pelvis, splenomegaly with multiple undefined hypodense focal areas of less than 1cm compatible with splenic microabscesses; at least 2 small hypodense punctiform masses in the liver (Figure 1). This suggested a differential diagnosis between microcytic pulmonary carcinoma and lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed hypoplasia, with no evidence of neoplastic cells. Gallium-67 scintigraphy revealed no source of inflammatory/infectious activity. PET/CT scan revealed hypermetabolic adenopathies in cervical, supraclavicular, axillary and mediastinal regions, and multiple hypermetabolic lung nodules in subpleural regions. Splenomegaly showed multiple hypermetabolic nodules, and hypermetabolic focal lesions in the C3, C4, and D8 vertebral bodies, and the fourth costal arch. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic and antifungal treatment, the patient still suffered fever spikes with significant constitutional syndrome and weight loss. All the cultures, blood tests, the intradermal PPD test, bacilli sputum cultures, pleural fluid, and urine, as well as pleural fluid adenosine deaminase were repeatedly negative. A mediastinoscopy was performed with biopsies of 2 adenopathies. The pathologic diagnosis was described as necrotic granulomatous lymphadenitis highly indicative of mycobacterial infection. No acid-alcohol-resistant bacilli or fungi were found in the histochemical stains. In view of this, and the patient's symptoms, with a strong suspicion of tuberculosis infection, we decided to begin treatment with tuberculostatic drugs (rifampin, isoniazid, and ethambutol).

The patient then progressed favourably; the fever remitted, his general condition improved and he gained weight, even enabling physiotherapy and mobility. A control CT scan 2 months after beginning treatment showed a significant reduction in the size and number of mediastinal adenopathies, fewer paratracheal adenopathies, a decrease in the size and density of the parenchymal lesions in the lungs, and the disappearance of the splenic masses. Only a hypodense lesion remained at the anterior pole of the spleen which was smaller than in the previous CT scan (Figure 2).

Therefore, the diagnosis was disseminated TB probably due to TB reactivation in the patient in dialysis under chronic corticosteroid treatment. The diagnosis was made using anatomical pathology and the patient’s clinical manifestations. In this type of cases, diagnosing the infection is difficult because the detection and laboratory tests are usually negative. It is also difficult because patients have unspecific clinical symptoms, and due to its extrapulmonary location; thus, the diagnosis and onset of treatment are usually delayed.5 We agree with other authors that levels of suspicion need to be maintained high and early empirical treatment needs to be administered which reduces mortality.

Figure 1. CT scan with contrast at the level of the spleen with multiple lesions

Figure 2. CT scan with contrast at the level of the spleen after 2 months of treatment with tuberculostatic drugs