Introduction: Measurement of dialysis dose by methods based on urea kinetics (Kt/VUREA) are hardly applicable to critical ill patients with acute renal failure (ARF). However, it is the base of the ADQI consensus recommendation for the target minimum dose. Objetive: To evaluate the usefulness of the real-time measurement of delivered dialysis dose (Kt) by means of the ionic dialysance (KtID) in the critically ill patient and to compare adequacy of dialysis dose between KtID and traditional Kt/VUREA. Material and methods: Prospective observational study in 17 critically ill patients with ARF requiring acute hemodialysis with a predefined prescription for the study (51 measures). Results: The mean delivered Kt/VUREA was 1.19 ± 0.14, with 59% of the sessions with values equal or above the ADQI recommendation. On the contrary, the mean KtID values obtained was 37.6 ± 1 l, with only 29.4% of the sessions being equal or greater than the recommended values. Conclusions: Dialysis dose monitoring by means of KtID reveals a lower degree of adequacy as compared to the traditional Kt/VUREA method. The dynamic character of KtID monitoring can allow the adaptation of each dialysis sessions («K» and/or «t») in order to achieve the recommended dose.

Introducción: La medida de la dosis de hemodiálisis basada en la cinética de la urea (Kt/VUREA) adolece de problemas de aplicabilidad en el paciente crítico con insuficiencia renal aguda (IRA). No obstante, las recomendaciones de consenso sobre la dosis se basan en el Kt/VUREA. Objetivo: Evaluar la utilidad de la medida en tiempo real de la dosis de diálisis suministrada (Kt) mediante dialisancia iónica (KtDI) en el paciente crítico y el grado de adecuación de la dosis en comparación con la medida estándar del Kt/VUREA. Material y métodos: Estudio prospectivo observacional de medida de dosis en 17 pacientes críticos con IRA sometidos a 3 sesiones de diálisis intermitente con prescripción predefinida para este estudio (en total 51 medidas). Resultados: El Kt/VUREA medio suministrado por sesión fue de 1,19 ± 0,14, con un 59% de sesiones consideradas adecuadas por lo recomendado por la ADQI. Por el contrario, la media de KtDI obtenida fue de 37,6 ± 1 l, con sólo un 29,4% igual o por encima del valor mínimo recomendado. Conclusiones: La monitorización de la dosis mediante KtDI revela un menor grado de adecuación en comparación con el Kt/VUREA. El carácter dinámico de la medida de KtDI puede permitir la adaptación de cada sesión de diálisis («K» y/o «t») con el fin de lograr el objetivo de dosis mínima.

INTRODUCTION

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a frequent complication in critical patients (with an incidence rate of between 5 and 25%), and it increases mortality significantly, particularly in cases that require renal replacement therapy, for which mortality can reach rates between 50 and 70%.1 There is no agreement whether the intermittent haemodialysis (IHD) dose for ARF in the critical patient is positively linked to survival. A study published in 2002 indicated that daily dialysis improved survival and accelerated renal recovery,2 although this idea was refuted in a very large study published recently.3 One of the criticisms of the first study was that mean Kt/VUREA supplied per session was only 0.94, compared with 1.3 in the second study. From these studies and others, we deduce that there is a minimum effective dose that should be reached, and that a regimen based on IHD lasting four to five hours on alternate days has a similar mortality to regimens with a higher frequency, provided that the dose administered per session is appropriate. The problem with calculating the dialysis dose in a critical patient is that no method has been validated to date. VUREA is difficult to estimate in acute patients, and therefore Kt/VUREA, which has been thoroughly validated for calculating IHD doses in ARF patients, should not be used for patients in critical condition. Although this is well-known, the ADQI (Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative) recommendations are based on the Kt/VUREA 4 method, which is used in most important studies.2,3 In recent years, one method for measuring IHD dose, ionic dialysance (ID) has been validated for CRF.5 The study is based on continuous monitoring of the dialysate conductivity which some haemodialysis monitors measure automatically. Recently, one study used this method in critical patients with ARF and compared it with the gold standard method of fractional dialysate sampling, which showed excellent correlation (0.96) between KtID and Ktdialysate. 6 The main objective of the present study was to evaluate application of the KtID measurement in normal clinical practice and compare it with the Kt/VUREA method, thus evaluating the prevalence of adequate dialysis in critical patients with ARF.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This prospective observational study was carried out in Hospital Clínic of Barcelona between September 2007 and June 2009. It includes all critical patients with ARF on renal replacement therapy with intermittent haemodialysis in a standard regimen of sessions lasting at least three hours every 48 hours who were treated by our service during that period. Vascular access consisted of a percutaneous 11.5 F catheter that was either femoral (24cm long) or jugular (15 or 20cm long depending on whether it was on the right or left, respectively). The dialysis characteristics were identical in all patients and similar to the treatment systematically applied in our centre: Fresenius 4008S monitor, frequency of every 48 hours, duration four hours, FX 60 membrane (Fresenius, surface area 1.4m2 ), blood flow of 250ml/min, dialysate flow 500ml/min, conductivity value of 14.5mS/cm and dialysate temperature of 35-36º C. In all dialysis sessions, Kt was determined using ID (KtID) and during the first three IHD sessions indicated in each patient, we determined Kt/VUREA by the Daugirdas7 method. In addition, we registered several variables that may affect the administered dialysis dose, such as the need for vasoactive drugs, mechanical ventilation, septic shock, catheter dysfunction requiring reversal of the arterial and venous lines, and episodes of hypotension during the session defined as a drop of 20mmHg in systolic pressure after beginning the dialysis or a need to increase the dose of vasoactive drugs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 15.0 (Chicago, USA). Values are expressed as a mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparison of means was performed using Student’s t-test or nonparametric tests for variables without a normal distribution. Qualitative variables were compared using Chi-squared test. Statistical significance was established for p-values < 0.05.

RESULTS

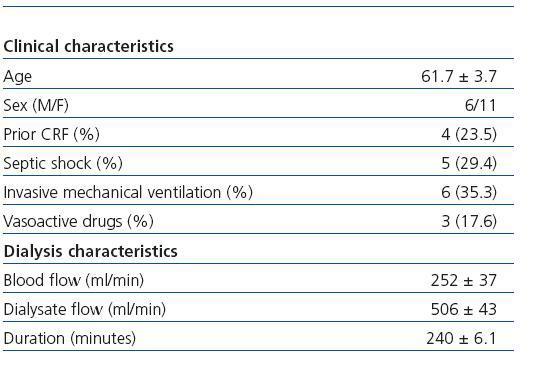

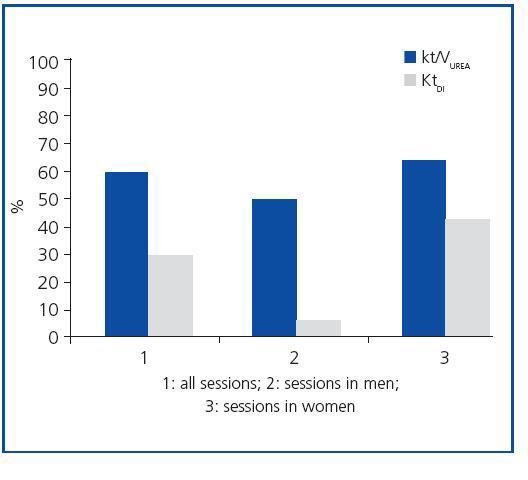

The study included 17 critical patients with ARF (six men and eleven women) with a mean age of 61.7 ± 3.7 years. Five of them were admitted to the ICU due to septic shock. Six patients were treated with invasive mechanical ventilation, and three required treatment with vasoactive drugs (noradrenaline or dopamine) in low doses (table 1). The characteristics of the dialysis sessions corresponded with the guidelines for the present study (table 1). The mean Kt/VUREA per session was 1.19 ± 0.14; 59% of the sessions had a value higher than that recommended by ADQI (1.2 or higher, regardless of sex), with 50% of men and 63.3% of women receiving the minimum required dose (figure 1). Meanwhile, the mean KtID was 37.6 ± 1L, and the minimum recommended KtID was reached in only 29.48 of the sessions (40L for women and 45L for men). Mean KtID values were 37.5 ± 1.5L for men and 37.6 ± 1.3L in women. If we consider the KtID values recommended for patients with chronic renal failure (CRF) according to Lowrie et al8 (KtID between 45 and 50L for men and KtID between 40 and 45L for women), recommendations were only met in 42.4% of all sessions for women and 5.6% of sessions for men (figure 1). There were no significant differences in the mean Kt/VUREA or mean KtID among patients grouped according to sex, need for vasoactive drugs, presence of septic shock, prior history of CRF, need for mechanical ventilation or hypotension episodes (data not shown). In sessions in which catheter dysfunction led to line reversal, values of KT/VUREA (0.84 ± 0.27 compared to 1.27 ± 0.16) and KtID (32 ± 1 compared to 37 ± 1.8) were numerically lower, but the difference did not reach a statistically significant level (p = 0.28 and p = 0.22, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the dialysis dose administered to a group of ARF patients in critical condition and compared the dialysis adequacy between direct measurement using KtID and Kt/VUREA, the classical method which is still being recommended. We observed that use of KtID can identify the patient subgroup which appears to receive an adequate dose of dialysis according to the Kt/VUREAmeasurement, but which could be considered as underdialysed. This observation concurs with that of a recent study of CRF patients in which the KtID value identified between 30 and 40% of the patients as underdialysed, although they met the minimum dosage of 1.3 recommended for CRF according to the Kt/VUREA measurement.9 Furthermore, among the ARF patients we see a low percentages of compliance with one method or another, which points to the need to focus our efforts on using a reliable, easy method for calculating the proper dose in these patients whose mortality rate is high. Although there have recently been doubts about the correlation between dialysis doses and survival in ARF,2,3 it is true that there is a minimum dialysis dose in this patient group, established as a Kt/VUREA level of 1.2 which is partly based on recommendations for CRF patients.4,10 However, specific studies in ARF patients will be necessary in order to determine the minimum effective dose. In any case, we know that this measurement is not transferrable to this type of patients who are not in a state of metabolic equilibrium and have an elevated protein catabolism, changing volaemic states, possible residual renal function, and in whom the estimated urea distribution volume (VUREA) is uncertain. Therefore, while VUREA may be inferred from total body water volume in healthy individuals or those with CRF, it has been observed between 7 and 50% higher in acute patients.11 Underdialysis is common in ARF. Moreover, a study in ARF patients showed that 70% of the treatments provided a Kt/VUREA value below 1.2, and that patient weight, sex and blood flow affected the resulting dose.12 Various factors are involved in each haemodialysis session, and they may affect dialysis effectiveness. It therefore seems logical that control systems were created to measure the dose the patient receives each session, in real time. At present, different monitors include biosensors that use the machine’s own conductivity probes to provide non-invasive measurements of the effective ionic dialysance, equivalent to urea clearance (K). This enables us to calculate the dialysis dose without a work overload or analytical measurements, and at no additional cost.13-15 Using Kt has its advantages. Both K and t are real measurements from the monitor, cannot be manipulated by the user and may be used in all dialysis sessions. Initial recommendations in 1999 were based on a minimum Kt of 40 to 45L for women and 45 to 50L for men with CRF8. These indications were subsequently validated,16 and it was observed that patient group receiving between 4 and 7 litres less than the prescribed amount experienced a 10% increase in mortality; the group receiving between 7 and 11 litres less experienced a 25% increase; and the group with 11 or more litres less than the prescribed amount experienced a 30% increase. SEN (Spanish Association of Nephrology) guidelines recommend a minimum of 45L of Kt for CRF patients who have ionic dialysance monitors.17,18 There is no minimum recommended dose of KtID in ARF, and no data about its effect on mortality, which is why we have taken the recommendations for CRF in the lowest value in the range. The main advantage of measuring KtID automatically is that it permits us to adapt the conditions of each dialysis session in order to reach the optimal dose. On this topic, a recent study showed that in patients equipped with catheters in the haemodialysis programme, it was necessary to prolong the dialysis session by 30 minutes in order to reach target Kt, compared with patients with an arteriovenous fistula (IAVF).19 Although systematically prolonging dialysis sessions (to five hours, for example) in all acute patients is not an uncommon practice, it is true that this measurement is not always necessary3 and, in this sense, continuous KtID monitoring may help in adapting session length in order to reach the minimum recommended dose. In conclusion, measuring the dialysis dose using the KtID method identifies a higher number of inadequate sessions than the standard Kt/VUREA method does, and the former therefore appears to be a useful method for delivering a minimum dialysis dose in ARF patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Grupo de Trabajo del Enfermo Crítico (Critically Ill Patients Study Group) at Hospital Clínic of Barcelona for its contributions to the completion of this study. The study was funded in part by FIS PI0800140 and ISCIII-Retic-RD06, REDinREN (16/06).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the included patients and haemodialysis sessions.

Figure 1. Percentages of haemodialysis sessions that met the proposed minimum criteria (Kt/VUREA >_40_1.2 for women; KtID >_45 for men).