Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, life-threatening condition, secondary to an overwhelming inflammatory process. When associated to rheumatic disorders, it can be called as macrophage activation syndrome.1 The main manifestations are unremitting fever, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly and multisystem organ failure. Unfortunately, there is no pathognomonic test, making the diagnosis hard to reach.2 It can be triggered by infection, malignancy, auto-inflammatory disease and immunosuppression associated with solid organ transplantation. Kidney transplant recipients are, particularly, at risk, and in most cases, infection is the identified trigger.3

We present a case of a 42-year-old woman with long standing Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and stage 4 chronic kidney disease (CKD), that following a cholecystitis complicated with cholangitis plus pancreatitis, presented with persistent fever accompanied by refractory anemia, despite laparoscopic cholecystectomy and combined large spectrum antibiotics having been performed. Concomitantly, her renal function declined, requiring hemodialysis initiation. During this period, she was under erythropoietin 30,000U per week and she received a total of 6 red cell units.

Laboratory investigation showed thrombocytopenia, anemia, with low reticulocyte production index, high lactate dehydrogenase, but normal haptoglobin. Folate and vitamin B12 were normal. Iron kinetics revealed low serum iron, normal transferrin saturation and an extremely high ferritin. Other inflammatory markers as leucocytes, C-reactive protein and procalcitonin were markedly elevated. She evolved with hepatic cytolysis and cholestasis, with normal bilirubin levels, normal lipase and slightly high amylase (104U/L). Lipid profile showed hypertriglyceridemia. Imaging studies exhibited hepatosplenomegaly and excluded biliary obstruction. No coagulopathy was found.

In the presence of bicytopenia, extremely high ferritin, increased liver enzymes, hypertriglyceridemia and hepatosplenomegaly, MAS was suspected. Bone marrow biopsy was not contributive for the diagnosis, and it was found an increase of serum soluble IL-2 receptor α (sIL-2Rα). After almost two weeks the diagnosis of MAS was made.

As there was strong data indicating a bacterial infectious process ongoing, it was assumed that was the trigger. Immunosuppression was withdrawn and antibiotics were maintained, although no agent was identified. Intravenous human immunoglobulin (IVIg) of 20g (500mg/kg) was administered for three days. She became apyretic and almost all analytical parameters improved (Table 1). However, she remained dependent on dialysis at discharge.

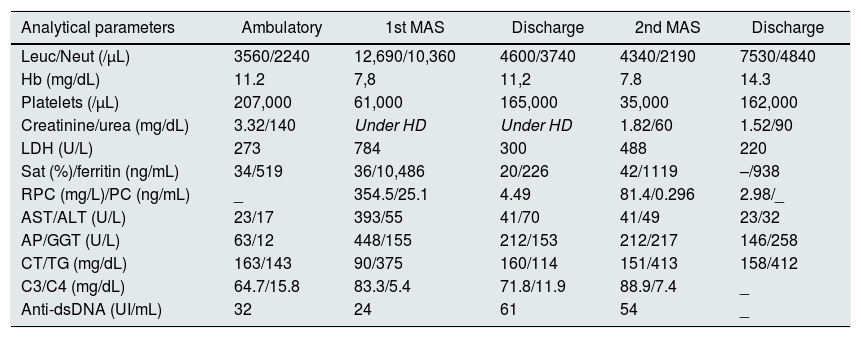

Evolution of analytical parameters.

| Analytical parameters | Ambulatory | 1st MAS | Discharge | 2nd MAS | Discharge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leuc/Neut (/μL) | 3560/2240 | 12,690/10,360 | 4600/3740 | 4340/2190 | 7530/4840 |

| Hb (mg/dL) | 11.2 | 7,8 | 11,2 | 7.8 | 14.3 |

| Platelets (/μL) | 207,000 | 61,000 | 165,000 | 35,000 | 162,000 |

| Creatinine/urea (mg/dL) | 3.32/140 | Under HD | Under HD | 1.82/60 | 1.52/90 |

| LDH (U/L) | 273 | 784 | 300 | 488 | 220 |

| Sat (%)/ferritin (ng/mL) | 34/519 | 36/10,486 | 20/226 | 42/1119 | –/938 |

| RPC (mg/L)/PC (ng/mL) | _ | 354.5/25.1 | 4.49 | 81.4/0.296 | 2.98/_ |

| AST/ALT (U/L) | 23/17 | 393/55 | 41/70 | 41/49 | 23/32 |

| AP/GGT (U/L) | 63/12 | 448/155 | 212/153 | 212/217 | 146/258 |

| CT/TG (mg/dL) | 163/143 | 90/375 | 160/114 | 151/413 | 158/412 |

| C3/C4 (mg/dL) | 64.7/15.8 | 83.3/5.4 | 71.8/11.9 | 88.9/7.4 | _ |

| Anti-dsDNA (UI/mL) | 32 | 24 | 61 | 54 | _ |

Leuc – leucocytes; Neut – neutrophils; Hb – hemoglobin; HD – hemodialysis; LDH – lactate dehydrogenase; Sat – transferrin saturation; RPC – reactive protein C; PC – prolcalcitonine; AST – aspartate aminotransferase; ALT – alanine aminotransferase; AP – alkaline phosphatase; GGT – gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; CT – cholesterol; TG – triglycerides.

During hemodialysis, no significant medical episodes were registered, and patient's hemoglobin levels were within the target, between 10 and 12g/dL, with an average of 100U/kg/week of erythropoietin.

Sixteen months after dialysis start, a living-donor kidney transplant from her brother was performed, and five days after, in the setting of a respiratory infection, she developed de novo persistent fever, bicytopenia, high ferritin, elevated DHL, hepatic cytolysis, cholestasis, hepatosplenomegaly and hypertriglyceridemia. This time sIL-2Rα was not above the cut-off, but still there were enough criteria for the diagnosis of recurrent MAS. Besides antibiotics and IVIg, corticosteroids dose was increased, tacrolimus maintained, and mycophenolate was withdrawn. Again, no microbiologic agent was identified, after an extended investigation, including bacterial cultures, large panel of virus and mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clinical and analytical improvement was rapidly registered (Table 1).

MAS has been associated to SLE since 1991, when it was first described by Wong et al.4 The reason why this association occurs is yet to be explained. The challenge is that signs and symptoms as fever, cytopenia and splenomegaly, present in MAS, can easily be part of a SLE flare-up.

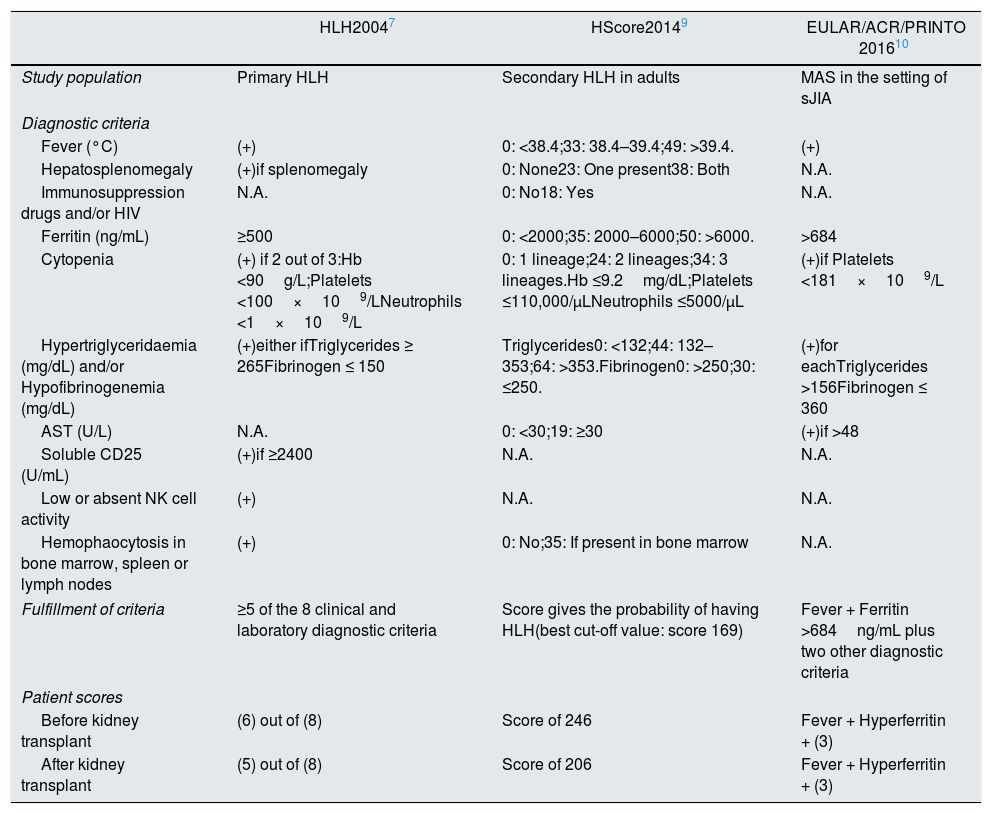

Due to HLH diagnostic complexity, different classifications have been proposed. Table 2 summarizes its characteristics. In each episode, our patient met the criteria in all classifications.

Different types of HLH classification criteria.

| HLH20047 | HScore20149 | EULAR/ACR/PRINTO 201610 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study population | Primary HLH | Secondary HLH in adults | MAS in the setting of sJIA |

| Diagnostic criteria | |||

| Fever (°C) | (+) | 0: <38.4;33: 38.4–39.4;49: >39.4. | (+) |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | (+)if splenomegaly | 0: None23: One present38: Both | N.A. |

| Immunosuppression drugs and/or HIV | N.A. | 0: No18: Yes | N.A. |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | ≥500 | 0: <2000;35: 2000–6000;50: >6000. | >684 |

| Cytopenia | (+) if 2 out of 3:Hb <90g/L;Platelets <100×109/LNeutrophils <1×109/L | 0: 1 lineage;24: 2 lineages;34: 3 lineages.Hb ≤9.2mg/dL;Platelets ≤110,000/μLNeutrophils ≤5000/μL | (+)if Platelets <181×109/L |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia (mg/dL) and/or Hypofibrinogenemia (mg/dL) | (+)either ifTriglycerides ≥ 265Fibrinogen ≤ 150 | Triglycerides0: <132;44: 132–353;64: >353.Fibrinogen0: >250;30: ≤250. | (+)for eachTriglycerides >156Fibrinogen ≤ 360 |

| AST (U/L) | N.A. | 0: <30;19: ≥30 | (+)if >48 |

| Soluble CD25 (U/mL) | (+)if ≥2400 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Low or absent NK cell activity | (+) | N.A. | N.A. |

| Hemophaocytosis in bone marrow, spleen or lymph nodes | (+) | 0: No;35: If present in bone marrow | N.A. |

| Fulfillment of criteria | ≥5 of the 8 clinical and laboratory diagnostic criteria | Score gives the probability of having HLH(best cut-off value: score 169) | Fever + Ferritin >684ng/mL plus two other diagnostic criteria |

| Patient scores | |||

| Before kidney transplant | (6) out of (8) | Score of 246 | Fever + Hyperferritin + (3) |

| After kidney transplant | (5) out of (8) | Score of 206 | Fever + Hyperferritin + (3) |

AST – aspartate aminotransferase; Hb – hemoglobin; HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; HLH – hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; NK – natural killer.

Infections and immunosuppression are frequent reported triggers.3 Both conditions can be present in the context of a solid organ transplantation, as the kidney. To date, HLH has been reported in less than a hundred kidney transplant patients, representing a rare complication.2

Most cases reported were triggered by all-kind infections, viral in its majority.2 More rarely, it can occur in the setting of neoplasms, and there are also some reports associated to allograft rejection.5

Although the best protocol is yet to be established, treatment of HLH should be oriented to the underlying disease and associated trigger. In order to diminish the hyperinflammatory process, high dose of steroids are usually indicated.6 In the setting of kidney transplant, besides steroids, and given the role of cyclosporine described in HLH-2004,7 calcineurin inhibitors should be maintained, and the antimetabolite suspended.2,5 The use of IVIg can be also beneficial and should be considered, especially if rejection is suspected.6,8

In conclusion, HLH is a rare condition and kidney transplants are at risk due to the immunosuppression regimens and susceptibility to infections. A high level of suspicion leads to early recognition and prompt treatment, which can be decisive for patient's prognosis. Due to its rarity, no strong evidence is available to guide therapy and for that reason we should consider each case individually.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.