Antecedentes: La libre elección no es fácil cuando se carece de información adecuada. Para ello son necesarios métodos de evaluación de la calidad asistencial que ofrezcan al paciente una información integral y comprensible de los servicios hospitalarios. Objetivos: Definir una propuesta metodológica para evaluar la calidad asistencial de los servicios hospitalarios, cuyos resultados sirvan para ofrecer una información útil al ciudadano. La propuesta debe fundamentarse en el consenso y en la experiencia de los especialistas médicos y definir complementariamente vías de mejora. Métodos: Estudio Delphi sobre calidad asistencial en Nefrología, estructurado en tres apartados: evaluación de resultados, medios necesarios para la calidad, e importancia del consejo médico y de la encuesta a especialistas. El cuestionario fue cumplimentado por un panel formado por 32 nefrólogos. Resultados: Los nefrólogos aceptaron 55/62 (89 %) de los criterios de resultados en calidad asistencial. También aceptaron 87/92 (95 %) de los medios propuestos para la calidad asistencial. El 81 % de los nefrólogos consideró de actualidad el consejo médico de un especialista a un paciente acerca del servicio donde podrían tratar mejor su enfermedad. Un 86 % creyó oportuno incluir encuestas sobre consejo médico como criterio adicional en la evaluación de la calidad asistencial. Conclusiones: Es posible obtener una propuesta metodológica consensuada para la evaluación y mejora de la calidad asistencial que incluya resultados de calidad asistencial, medios para la calidad asistencial y el consejo médico derivado de encuestas a especialistas para identificar los mejores servicios. Este método podría facilitar una orientación fiable y comprensible para el ciudadano.

Background: Free choice is not easy when there is a lack of information. Methods for evaluating quality of care to provide patients with comprehensive and understandable information on hospital departments are therefore necessary. Objectives: To draft a methodological proposal for evaluating quality of care of hospital departments, the data of which can provide citizens with useful care quality information. The proposal should be based on consensus and on the experience of medical specialists, defining thus complementary paths to improvement. Methods: A Delphi study on the quality of care in Nephrology, comprising three phases: assessment results, necessary means for quality, and importance of medical advice and surveys among specialists. The questionnaire was administered to a panel of 32 nephrologists. Results: The nephrologists accepted the outcome criteria on quality of care 55/62 (89%), as well as the proposed means for quality of care 87/92 (95%). 81% of the nephrologists reported the validity and topicality of providing patients with specialist advice as to the most adequate department to better treat their kidney diseases. 86% of the panellists deemed appropriate to include surveys on medical advice as additional criteria for the evaluation of quality of care. Conclusions: It is possible to obtain a consensus-based methodological proposal for the evaluation and improvement of quality of care which includes results on quality of care, means for quality of care, and medical advice based on surveys carried out among specialists to identify the best Nephrology departments. This method could provide reliable and understandable guidance for citizens.

INTRODUCTION

Spanish Law 41/2002, also known as the Patient Autonomy Law1, defines free choice as the power of the patient or user to choose freely and voluntarily between two or more healthcare alternatives, various doctors and healthcare facilities. It also establishes that patients and National Health System users have the right to receive information on available healthcare departments and units, their quality and access requirements.

However, currently there is not enough information for patients to freely choose between different hospital departments. Therefore, methods are required to assess the quality of care provided by specific hospital departments and generate specific, comprehensive, reliable and easy to understand information for patients.

Hospitals often use different models for managing and improving quality, mainly following the Joint Commission Accreditation Model2, the ISO certification3,4, and the European Foundation for Quality Management Model5. These models are very useful and, both individually and collectively, provide a lot of information on areas for improvement6. Yet, they do not provide data on the specific quality of care provided by each hospital department.

The use of the medical history as a basic source of information may provide data more in line with this aim7. This approach uses indicators provided by the Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS), defined in 1981 for the first time by the European Economic Community, with the support of the World Health Organization and the Hospital Committee of the European Communities. In 1987, the MBDS was endorsed in Spain by the National Health Service Interregional Council and implemented in the different autonomous communities in the early 1990s.

Spain has recently approved the minimum data set for clinical reports8, which, along with the audits on the quality of clinical coding of diagnoses and procedures, will contribute to greater homogeneity of MBDS-based indicators9 and will likely increase the reliability of comparative studies between hospitals.

Examples of these indicators are some of those defined and used by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality10, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development11, the Spanish Society of Healthcare Quality12, the Ministry of Health13 and the autonomous communities14,15. However, in terms of free choice of specific healthcare departments and units, this great abundance of indicators does not provide enough information on differences between specialties nor provide an overview of the quality of the different healthcare activities carried out in each hospital department.

The main objective of this project was to develop a methodology for assessing the quality of healthcare in specific hospital departments, in order to provide high quality and easy to understand information that allows patients to freely choose specific hospital departments. A second objective was to define means and channels for improving the quality of healthcare. This method had to be supported by the knowledge and experience of those who know best the quality of care in their departments, that is, medical specialists. Our approach was to define and structure a model for assessing and improving the quality of healthcare16 and subsequently submit it to specialists for their opinion. We were also motivated by a desire for agreement and consensus, as the only way to achieve stable and lasting paths to improvement.

The recommendations of the Institute of Medicine for redesigning healthcare systems17, especially those related to improved quality and transparency, also encouraged us to work along these lines.

With this in mind, we considered an assessment method that included two complementary systems, one that assessed the quality of healthcare provided by hospital departments through outcome results and a survey asking medical specialists for the expert opinion on the best hospital departments in each field of medicine. We suggested the survey based on our belief that specialists’ opinions should be a new component of quality assessment models, since many patients with serious illnesses ask medical specialists where they can be treated with the best chance of being cured18. We also wanted a useful model so we established the complementary requirement of seeking avenues for improving the quality of hospital departments, not only for assessing them. We thought that the usual absence of indicators on structural, human and organisational resources prevented each hospital department from clearly seeing what it should or could do and the path it should follow to improve its quality of healthcare.

To achieve our objectives, we proposed a Delphi study19-23, since we were seeking first-hand, freely expressed information, and a consensus that could not be interfered with leaders stating their opinion. We started the project with a pilot study in two specialties: one medical (Nephrology) and the other surgical (Otolaryngology).

In this paper, we present the results obtained in the specialty of Nephrology. It is important to highlight the interesting studies published on this specialty24-26 and specifically on the quality of healthcare in Nephrology27-32, which were very useful in developing our project.

Amongst the results obtained, we highlight the high rate of participation of the nephrologists involved in the study, which was higher than expected for this type of studies33,34. This may reflect a desire to define new methods to assess and improve the quality of healthcare in Nephrology. We also highlight the large number of agreements obtained on indicators for assessing and means for improving the quality of healthcare. Acceptance of the web platform was an essential study tool since it was a major communication facilitator. Its use made defining and reviewing the model easier. Both the expert opinion of specialists on the validity of medical advice on the best Nephrology departments for treating different diseases and the agreement obtained on the existing relationship between image or prestige and quality of healthcare, were also significant results.

The most important conclusions were: first, the possibility of obtaining, by consensus, a basic methodological proposal for assessing and improving healthcare quality; and second, the validity of expert opinion by specialists to identify the best Nephrology departments for specific kidney diseases.

METHOD

Study design

A questionnaire was developed to be assessed in a Delphi study by a panel of experts in Nephrology from around Spain. The research team defined and structured a conceptual methodological proposal for assessing and improving the quality of healthcare in Nephrology11-16,27-32. The questionnaire was developed over several meetings in which the model and structure were defined, criteria and indicators were selected, the requirements necessary to form part of the expert panel were agreed upon and the minimum consensus for the acceptance of each proposal was established. The study was carried out in two rounds, with a four-week interval, in May and June 2012. The first round included 242 questions grouped into different areas of criteria, of which 203 were multiple-choice. The second round included all of the multiple-choice questions. In the second round, before answering each question, the panellists saw the group response percentages of the first round, as well as their own response, with the aim of facilitating the review of all their responses.

The questionnaire was administered to the experts through a web platform specifically designed for the study, with 24-hour open access. In this questionnaire, we requested the opinions and degree of agreement of the panellists with different statements in relation to the assessment and improvement of healthcare quality in Nephrology. The estimated time for completing the questionnaire was 2-3 hours in each round.

Participants

The expert panel consisted of nephrologists, since they were considered to be the professionals who have the best knowledge of the healthcare situation in Nephrology Departments. Panellists were selected using the following criteria: representative of the different Nephrology subspecialties, having at least ten years’ experience as a specialist, geographical diversity within Spain and a solid professional image for each expert in their main area of subspecialisation. The selection was carried out with the collaboration of the Spanish Society of Nephrology (S.E.N.), which conducted a pre-selection of experts who met the abovementioned criteria. Each expert who agreed to participate did so individually and did not know the composition of the rest of the panel.

Sample size

We initially planned for a minimum of 20 experts to participate. The S.E.N. provided a list of 40 nephrologists. Once we verified that they met the requirements established, we contacted them via post and e-mail, with 37 agreeing to participate. Of these 37, 32 started the questionnaire (86.5%). The study was completed by 32 experts (100% of those starting the questionnaire).

Context of the questionnaire

The questionnaire had three parts. The first two parts were presented as a “management game”. The experts were placed in a hypothetical situation. They became the new Heads of the Nephrology Department in a Hospital of medium/high complexity with the objective of improving the quality of healthcare while maintaining the previous year’s budget. Firstly, as Heads of the Nephrology Department, they were asked to analyse the quality of care delivered by the Department. For this purpose they were given the outcome results of the previous few years. Next, they prepared a scorecard with the indicators they deemed to be most important. Secondly, they were asked by the Hospital Administration to improve the quality of care. Since the outcome results provided information on past performance, the Heads of the Nephrology Department had to prepare a new scorecard with information on the resources available (structural, human and organisational resources). In this manner, they could manage existing resources better and request or implement those of a low cost that did not exist and thereby attempt to improve the quality of healthcare without changing the budget, in accordance with the Hospital Administration’s objectives.

The third part of the questionnaire was unrelated to the two previous parts. The experts were presented with another theoretical scenario: one of their relatives had been diagnosed with a nephrological disease and had asked the experts for their advice on the best Nephrology Department to treat their specific disease. This question was repeated for different kidney diseases.

Structure of the questionnaire

The questionnaire was divided into three sections: Section A focussed on healthcare quality outcome results, Section B on healthcare quality resources, and Section C on expert opinion regarding medical advice to select the best Nephrology Departments to treat specific kidney diseases.

In Section A (Healthcare quality results) we included criteria and indicators, or groups of indicators, divided under the following headings: Health results (mortality, complications, re-admissions and patient safety), Process management results (length of hospitalisation stay , outliers with regard to length of hospitalisation stay, delays in care and management of arteriovenous fistulas), Economic results (costs, productivity and work attendance rates), Perceived quality results (satisfaction survey and claims) and Scorecard of healthcare quality results (degree of updating, transparency, standards and weighting of criteria).

In Section B(Healthcare quality resources) we included criteria and indicators divided under the following headings: Structural resources (healthcare structuring, technology and techniques, use of medication, medical history, complementary healthcare activities, educational programmes, healthcare support and non-healthcare support within the hospital, and information technology (IT) and telemedicine), Human resources (doctors, nursing and assistant staff, dieticians and nutritionists), Organisational resources (department organisation standards, methods and assessment of healthcare quality for improvement) and Scorecard of resources for healthcare quality (need, degree of updating, transparency and weighting of criteria).

In Section C (Expert opinion on medical advice and the ability to select the best departments) different questions were asked about the ability of the expert to provide advice on the Nephrology departments where they thought the quality of care for specific diseases would be best, as well as the potential relationship between the image or prestige of a Nephrology department and the quality of its healthcare. Various questions were also included to determine the feasibility and relevance of a future survey to nephrologists about the image/prestige/quality of Nephrology departments.

Assessment scales

In the questionnaire, different assessment scales were used in accordance with the type of questions. Likert-type scales with five categories were used for most of the questions. We decided that for Section A the response categories would be “Essential, Important, Unnecessary, Leads to confusion and I don’t know”. No intermediate option between “Important” and “Unnecessary” was provided, since a questionnaire to decide on criteria/indicators that are necessary for knowing the quality of care provided by a department did not accept this intermediate option. For the analysis, these categories were grouped in order to perceive the results more clearly. There were specific scales for some questions because as the use of generic scales was inadequate for their content. In only a small number of questions more than one choice was possible. In all of the multiple-choice questions, we included a section for comments from the panellists. Some questions were answered solely by comment.

Statistical methods

We agreed that, as a minimum, any criteria or proposal should obtain the support of 70% of the experts in order to be included in the new method to assess quality of care.

In each multiple-choice question in which only one response was allowed, we obtained the percentage of responses in each category. For those in which more than one answer was permitted, we obtained the percentage of panellists who selected each category.

At the end of Sections A and B, the panellists gave a score between 0 and 10 to each group of criteria, according to whether they thought that there was a lower or higher relationship between these criteria and the quality of healthcare. The results were summarised using means and medians.

RESULTS

The study was completed by all 32 nephrologists who started it. After concluding the two rounds of the Delphi questionnaire, each panellist individually accepted that their name would be amongst those of the experts who had participated in the study. The composition of the panel was not made public on this occasion either.

In the first round, the response rate was 99.9% for the questions of Section A, 99.7% for those of Section B and 99.6% for those of Section C. In the second round, 26 experts (81.3%) changed some of their answers while 6 did not change anything. The percentage of multiple-choice answers changed in the second round was 7%, since there were 453 changes in a total of 6496 questions (203 multiple-choice questions given to 32 experts). That is a mean of 14.2 changes for each of the 32 panellists (median 13.5).

The overall results of the study are presented in this paper.

Section A (Healthcare quality results)

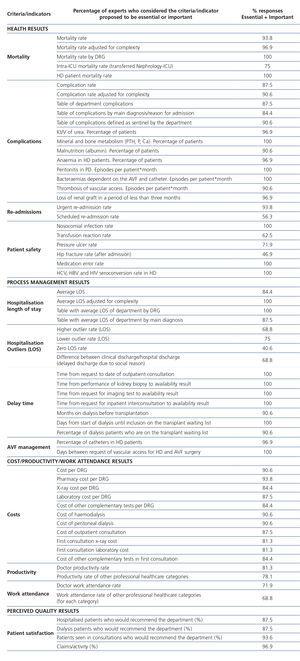

To perceive the results more clearly, we grouped the five response categories in this section, “Essential, Important, Unnecessary, Leads to confusion and I don’t know”, as follows: the percentage of “Essential + Important”, the percentage of “Unnecessary + Leads to confusion” and the percentage of the response “I don’t know”. The experts accepted 55 of the 62 criteria/indicators, considering them essential or important, with a mean acceptance percentage of 91.3%. Seven criteria/indicators were not considered essential or important by 70% of the experts. The results in this part of the study are summarised in Table 1 and in more detail in Addendum 1.

With respect to the transparency of the results Scorecard, 100% of the experts believed that it was essential or important that all doctors in the department had access to this information. 90.6% believed that it should also be available for the rest of the hospital departments. In terms of access of citizens to healthcare quality results, 62.5% thought it was essential or important. There was an agreement of 71.9% when we proposed that the indicators for citizens would reflect the same reality, but in a more positive manner. For example, the percentage of patients treated without complications, compared with the percentage of patients treated with complications. 75% of the experts considered that it would be sufficient to update this Scorecard every three months.

Finally, in this part of the questionnaire, we asked the experts to score the different groups of criteria assessed in Section A, assigning each group a value (between 0 and 10) in accordance with a lesser or greater conceptual relationship with healthcare quality within their specialty (Table 2).

With respect to the comparison standards, both for health criteria/indicators and management and economic criteria/indicators, the experts mainly chose (above 90%) national standards and, in a lower proportion, autonomous community and European standards.

Section B (Healthcare quality resources)

The five response categories in this section “A lot, Quite a lot, Little, Nothing and I don’t know” are grouped in order to perceive as clearly as possible the degree of agreement. We obtained the percentages for “A lot + Quite a lot” and “Little + Nothing” and that of “I don’t know”.

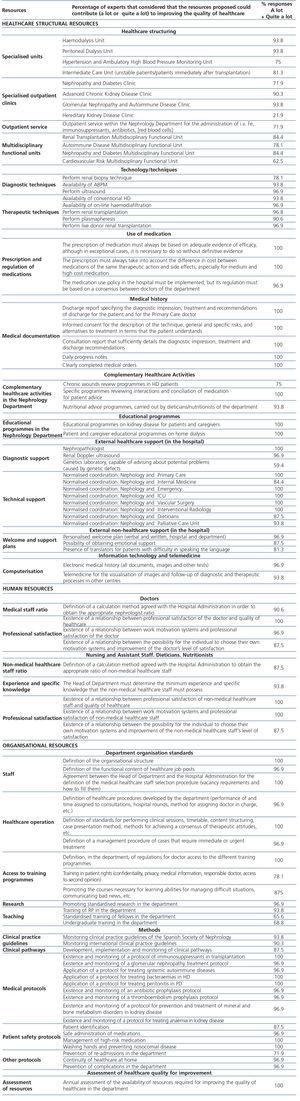

The experts accepted 87 of the 92 resources proposed, since they contributed or potentially contributed a lot or quite a lot to improving the quality of healthcare in Nephrology, with a mean acceptance percentage of 93.6%. In 5 proposals, we did not obtain the minimum support of 70% of the experts. The results are summarised in Tables 3, 4 and 5, and in more detail in Addendum 2.

With respect to obtaining a healthcare quality resources Scorecard, 96.9% of the experts believed that it was necessary to complement the results Scorecard and, of these, 100% believed that it was essential or important that all doctors of the department had access to this information. 78.1% thought that it was also appropriate for the rest of the hospital departments to have access. 75% of the experts considered an annual updating of the resources Scorecard to be sufficient.

At the end of Section B, experts were also requested to score the different areas or groups of criteria assessed and had to assign each area a value (between 0 and 10) in accordance with the lesser or greater conceptual relationship of the resources proposed with the improvement in the quality of healthcare within their specialty (Table 6).

Section C (Expert opinion medical advice and the ability to select the best Nephrology departments)

81.3% of the nephrologists considered that, when a patient has a serious illness, the patient himself or a family member should ask for the advice of a specialist about the department where they can receive the best treatment for their illness. Of these nephrologists, 61.5% believed the reason was that the patient trusted the expert advice more than any other information system, while the rest believed the reason was that no system offered clear information (30.8%) or that information systems were not transparent (7.7%).

All the experts thought that, if they themselves or someone close to them required help, they would ask a colleague in the relevant specialty for expert opinion on the best Hospital department for that problem. 59.4% indicated that they would also use the healthcare quality indicators and publications. None would search only for information, without also asking for advice.

We then asked them if they would be capable of offering advice or recommending a Nephrology information system for different diseases in their specialty (Table 7). We grouped the five response categories for this question “Yes, I think so, I am not sure, No and Any department” in order to facilitate the reading of results. We obtained the percentage of “Yes + I think so”, that of “I am not sure + No” and the percentage of the response “Any department”. We grouped options A and C in the last column, since we understand that both express the possibility of giving advice to the patient, which occurred in a mean of 87.5% cases. Only in Fabry disease and the haemolytic-uraemic syndrome was there a certain degree of difficulty in making a recommendation.

The experts believed that the reason for which an information system was more frequently recommended was mainly direct scientific visibility through conferences and publications (73.8%).

On the appropriateness of administering this type of surveys to nephrologists, 86.2% thought it was appropriate and even include them as additional criteria in the assessment of healthcare quality, since the Image/Prestige concept, according to 87.5% of the experts, was very or quite related to that of healthcare quality.

DISCUSSION

There was a high participation rate and a high degree of involvement in the responses by the experts, who on many occasions expanded on their answers with comments at the end of each question. Their participation and involvement are two of the most valuable aspects, taking into account that both are considered the main difficulties in any Delphi study. The questionnaire’s length did not seem to have a negative influence, which, in our opinion, shows the experts’ high level of commitment to the study.

The web platform also contributed to this study, since it made completing the questionnaire convenient, as it could be done from any location and at any time. The remote interaction between experts facilitated an anonymous, tension-free revision of the ideas as the result of individual reflection on the group’s opinions. We believed it was important that the experts had the chance to address all the issues again in the second round and not only those selected due to a lack of agreement. The changes and clarifications of several questions in the second round confirmed this.

The broad agreement of the experts with most of the criteria and indicators proposed for the assessment and improvement of the quality of healthcare seems to be a consistent and solid basis for a future healthcare in Nephrology assessment and improvement model. It is necessary to highlight the favourable opinion towards the need for better organisation in the departments and the incorporation of internal assessment of healthcare quality with the support of some central departments such as Medical Documentation or Quality or of some Clinical Commissions. Furthermore, we must highlight the desire for better knowledge of the costs as guidance for more efficient processes.

Another important agreement was the validity of the specialist’s expert opinion advice as guidance for the patient on the best departments for different diseases. Most experts related the image or prestige of a department with the quality of healthcare and declared their ability to identify the best departments for the treatment of specific diseases. It should be noted that they considered scientific visibility as the main criterion for selecting the best departments and making a recommendation. The experts demonstrated their support for the future development of surveys for specialists on the image/prestige/healthcare quality of departments, which we considered to be important added value for finding the best departments for treating different diseases.

Finally, the great interest shown by nephrologists in participating in the construction of a methodology for assessing and improving the quality of healthcare, and most probably, its future implementation, suggests that seeking a consensus is a correct approach. The experts have shown their disposal and willingness to build Experience-based Quality together.

This methodology could have the following practical applications: internal assessment of healthcare quality in Nephrology departments, the development of guidelines for improving healthcare quality in each Nephrology department, comparative studies between Nephrology departments of different hospitals, surveys for nephrologists as a complementary method for assessing the quality of healthcare delivered by a department and information for citizens on Nephrology departments.

Study limitations

The results of the study may have limitations in terms of their applicability to other geographical settings and specialties, mainly with regard to the criteria/indicators selected and the structure of the expert panel. Further research is needed on the definition, validation and feasibility of indicators in Nephrology.

CONCLUSIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Marta García, Mercedes Guerra, Caroline Hall, Luis Miguel Molinero and Ricard Rosique for their important work in the different parts of this study. AO belongs to the ISCIII RETIC REDINREN RD012/0021 ERDF funds and has intensified the research activity of the ISCIII.

We are also deeply grateful to the S.E.N. for the scientific support granted to this project and to the nephrologists who took part of the expert panel for their generous participation in the study (Appendix 3).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article. The study was fully financed by the Institute of Health Research of the Jiménez Díaz Foundation (IIS-FJD). The responsibility for the contents of this article corresponds exclusively to its authors.

Table 1. Agreements on criteria/indicators for the assessment of healthcare quality.

Table 2. Weighting of criteria/indicators for the assessment of healthcare quality.

Table 3. Resources that could contribute to improving the quality of healthcare. Structural resources.

Table 4. Resources that could contribute to improving the quality of healthcare. Human resources.

Table 5. Resources that could contribute to improving the quality of healthcare. Organisational resources.

Table 6. Weighting of resource groups for improving the quality of healthcare.

Table 7. Medical advice. Opinion on the specialist¿s ability to give guidance to patients who require treatment for certain nephrological diseases

Healthcare quality results: proposals on Nephrology criteria/indicators.

Resources that could contribute to improving the quality of healthcare.

Expert panel of the Nephrology Delphi Study (in alphabetical order)