Antecedentes: El análisis del coste de la enfermedad renal crónica basado en datos individuales, por componentes y modalidades terapéuticas no ha sido publicado en España. Objetivos: a) Estudiar los costes sanitarios de un año de tratamiento con hemodiálisis (HD), trasplante renal (TxR) de cadáver y reno-páncreas (TxRP), y de la enfermedad renal crónica avanzada (ERCA) E4 y E5. b) Evaluar la eventual relación entre disparidad sociocultural, costes y modalidad de tratamiento. Métodos: Estudio observacional de: 1) 81 pacientes con ERCA (53 E4 y 28 E5); 2) 162 con más de 3 meses en HD y 3) 173 con más de 6 meses Tx (140 TxR y 33 TxRP). Los costes se evaluaron en cinco categorías: 1) sesiones de HD, 2) consumo farmacéutico, 3) hospitalizaciones, 4) atención ambulatoria y 5) transporte. Se realizó una encuesta de parámetros sociodemográficos. Resultados: El impacto económico de la HD fue de 47 714 ± 18 360 € (media ± DS), el del Tx de 13 988 ± 9970 €, y el de la ERCA 9654 ± 9412 €. El coste de la HD fue el más elevado en todas las partidas económicas. Los costes fueron similares entre TxR y TxRP. En ERCA, a mayor deterioro renal, mayor coste (E4 7846 ± 8901 frente a E5 13 300 ± 9820, p < 0,01). Los pacientes Tx tenían mejor estatus sociocultural, mientras que los de HD presentaban el peor perfil. No encontramos diferencias en los costes entre los tres grupos socioculturales. Conclusiones: La HD conlleva el mayor impacto económico en todas las partidas, incrementando cinco veces el coste del paciente ERCA y tres veces el del Tx. Optimizar la prevención precoz y el Tx, llegado el caso, deben ser estrategias prioritarias. Este análisis invita a reflexionar acerca de si el estatus sociocultural puede influir en ventajas de oportunidades para el Tx.

Background: The cost analysis of chronic kidney disease based on individual data for treatment methods and components has not been published in Spain. Objectives: a) To study the health costs of a year of treatment with haemodialysis (HD), deceased donor renal transplantation (RTx), renal-pancreas transplantation (RPTx), and S4 and S5 advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) b) Assess the potential relationship between sociocultural diversity, costs and treatment method. Methods: Observational study of: 1) 81 patients with ACKD (53 S4 and 28 S5) 2) 162 with more than 3 months on HD and 3) 173 with a Tx for more than 6 months (140 RTx and 33 RPTx). The costs were assessed in five categories: 1) HD sessions, 2) drug intake, 3) hospitalisation, 4) outpatient care and 5) transportation. We carried out a survey with socio-demographic parameters. Results: The financial impact of HD was €47,714±18,360 (mean±SD), that of Tx €13,988±9970, and that of ACKD €9654±9412. The cost of HD was the highest in all financial items. The costs were similar between RTx and RPTx. In ACKD, the greater the renal deterioration, the greater the cost is (S4 €7846±8901 versus S5 €13,300±9820, P<.01). Tx patients had the best sociocultural status, while HD patients had the worst profile. We did not find differences in costs between the three sociocultural groups. Conclusions: HD has the greatest financial impact in all items, five times higher than the ACKD patient cost and three times than the Tx patient cost. Optimising early prevention and Tx, if appropriate, must be priority strategies. This analysis invites us to think about whether sociocultural status can have an influence on opportunities for Tx.

INTRODUCTION

The population with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who require renal replacement therapy (RRT) is constantly growing1,2. This is fundamentally due to an increase in the elderly and diabetic population3. RRT is a major component of healthcare spending, given that, although the volume of patients is lower than 0.1% of the population, the healthcare budget is 2.5% for this population4. According to data of the EPIRCE (Chronic Renal Failure Epidemiology in Spain) study, the Spanish population that suffers advanced CKD (ACKD) stages (S) 4 and 5 is approximately 0.3% (around 130,000 individuals)2, to which we must add the 50,000 patients who are on RRT: 51% kidney transplant patients (RTx), 44% on haemodialysis and 5% on peritoneal dialysis (PD)5.

In healthcare economics, cost plays an important role, especially in chronic diseases, such as CKD and diabetes, given the ageing population and the progressive number of exposed patients. Therefore, priority must be given to addressing the high social and financial costs of treatment6. However, the information available on a national level is poor and is fundamentally focussed on HD7,8. In any case, it is very difficult to compare studies, since the cost estimation varies depending on whether or not different direct and indirect components are included. Likewise, there is usually wide variability depending on the public or subsidised status of hospitals and the different use of resources. It is even more complicated to compare costs between countries with different healthcare models, both in terms of financing and in the provision of services9-11.

Despite these difficulties, knowledge and analysis of costs is both important and necessary6. With this information we can achieve an overview of the effect of illness on the use of resources. Furthermore, knowledge of the cost distribution between the different components would allow us to identify areas of inefficiency, in order to allocate resources better12.

Many studies have shown that RTx and PD are considerably cost-effective when compared with HD13-16. In our setting, we have heterogeneous information about the cost of HD and PD; however, the cost of ACKD patient treatment has not been analysed in our country and we do not have detailed data on patients who have received transplants.

Our objective was to study the financial impact of treatment with HD, deceased donor RTx and renal-pancreas transplantation (RPTx), and the management of S4 and S5 ACKD (not yet on dialysis). A secondary objective was to investigate the demographic and sociocultural profile of this population and its possible association with cost and method of treatment.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Design

Observational study of direct healthcare costs during one year of treatment for patients affected by ACKD and on RRT with HD, RTx and RPTx. The study population comprised the Northern Health Area of the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, and the reference hospital was the Hospital Universitario de Canarias (HUC). This region has a population of approximately 400,000 inhabitants.

Study subjects

We evaluated three populations, who were initially surveyed between November 2009 and December 2009, and we finished collecting data in December 2011. Patients who completed at least six months of follow-up were included in the final analysis and the cost allocation was extrapolated to one year. Those who were not followed up for six months were excluded due to the study period being considered to be too short. Likewise, exclusion criteria included the following: 1) patients whose circumstances or illness may have interfered with the study (for example, drug users and individuals with cognitive deficiencies or disorders); 2) when informed consent could not be obtained or was not given; 3) a lack of adherence to medical recommendations or a lack of collaboration from the patient or their responsible family member.

The final study included:

In the HUC’s ACKD clinic follow-up: 81 patients, 53 S4 and 28 S5.

HD patients who had spent at least three months on this form of RRT: 85 HUC patients and 77 patients from the Hospital Tamaragua. These are two subsidised hospitals with a dialysis cost established in an agreement.

Patients followed up in the HUC’s RTx clinic who had received their transplant at least six months before: 140 patients with RTx and 33 with RPTx.

Healthcare costs

We defined “cost” as the consumption of goods and services valued in monetary terms, to achieve a certain objective or obtain a certain product. In order to estimate the cost, we used the prevalence cost method, i.e., the direct healthcare costs attributable to the illness in the study year17. These were organised into five main categories: 1) HD sessions, 2) medication use, 3) hospitalisation, 4) outpatient care in clinics, emergency departments and complementary tests and examinations, and 5) transportation use.

Haemodialysis sessions

For the specific cost of HD sessions, there are different models depending on the country. The model applied in our setting is the one most commonly used in Europe, i.e., a fixed amount per dialysis session, which is adjusted to a protocol of action. In the Official Canary Gazette18, for this method, there is just one activity that is charged: the HD session, with certain variability depending on the hospital and the services. The cost of HD in accordance with the agreement established included the cost of consumables, with a supplement for special membranes accepted for 10% of patients, repayment of non-disposable material, staff and medication administered during the HD session, with the exception of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA). As such, we applied €146 for the HUC outpatient unit and €158 for the Hospital Tamaragua. There was no difference in reimbursement depending on the number of hours per session or the method of treatment. Regular examinations that were carried out on these patients were included in the dialysis reimbursement, and as such, they were not included under a different heading. The normal HD regimen in all hospitals was four hours, three times a week.

Medication expenses

Information on the consumption of medications and diagnosis material for self-monitoring was taken from clinical databases and from surveys carried out on patients and/or their family members. The cost was obtained by calculating the price of each unit in euros and multiplying it by the dose. The costs were obtained from different sources, such as the Pharmaceutical College Medications Database. This expense was expressed in euros/patient/day or year, as appropriate, in the presentation of results. In this study, we did not consider the discounts offered by many pharmaceutical companies in a different format.

Hospitalisation

The volume of hospital admissions was obtained from the two hospitals where the patients were admitted. We recorded the total number of admissions over the study period and applied the attributable fractions of morbidity for each diagnosis code of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) and their subsequent processing by diagnosis-related group (DRG). DRG, as a patient risk-adjusted system, incorporate a cost estimator, which is a measure of the mean complexity of the patients, and the “relative weight”, or level of resource consumption attributable to each patient type or group19. The mean cost of each DRG was obtained from the Ministry of Health and Consumption’s Health Information System.

Outpatient care

Outpatient care includes hospital or primary care centre consultations, vascular access for HD carried out in an outpatient setting, and complementary and imaging studies. Information on the use of these healthcare resources was obtained from three sources: a review of clinical records, a review of digital hospital records and a review of the survey carried out on patients and/or their family members. To allocate the cost of consultations and complementary studies, we used the HUC invoicing tables, the reimbursement tables established by the Canary Health System (SCS) and the allocations for procedures published in the Official Canary Gazette18.

Transportation

We must add the cost for use of transportation to hospitals to that of the HD sessions. This expense was obtained from the reimbursement tables established by the SCS for the use of private cars, taxis, health buses, non-emergency ambulances and emergency ambulances. We also recorded the possible use of transport for travel to clinics or for imaging tests.

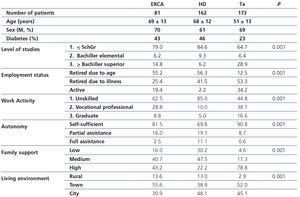

Sociodemographic variables

We carried out a generic survey on patients and/or a relative, according to the individual circumstances. The following data were collected: age, sex, underlying disease, educational level, employment status and work activity, autonomy, family support, living environment (urban, rural). Subsequently and with the aim of simplifying the analysis, we summarised and grouped the scores in accordance with the level of studies and work activity. In this manner, patients were classified into three groups of sociocultural status: 2 points: lower, 3 points: lower-middle, >3 points: middle-upper.

Data analysis

The results of this study are fundamentally descriptive, and as such, we have exclusively used basic statistics tests. Given that the cost values were extreme in some patients, there was an asymmetric distribution towards high values. This is highlighted because the mean was higher than the median, particularly for the expenses of hospitalisation and consultation, not used in many cases. For these types of data with many extreme values, the median must be considered to be a stronger comparison parameter; however, the arithmetic mean is considered to be more informative of the total cost for decision-making about health policies20-24. Finally, we presented the results in both formats, mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (interquartile range [IR]). The statistical analyses were carried out with the SPSS 17.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, ILL).

RESULTS

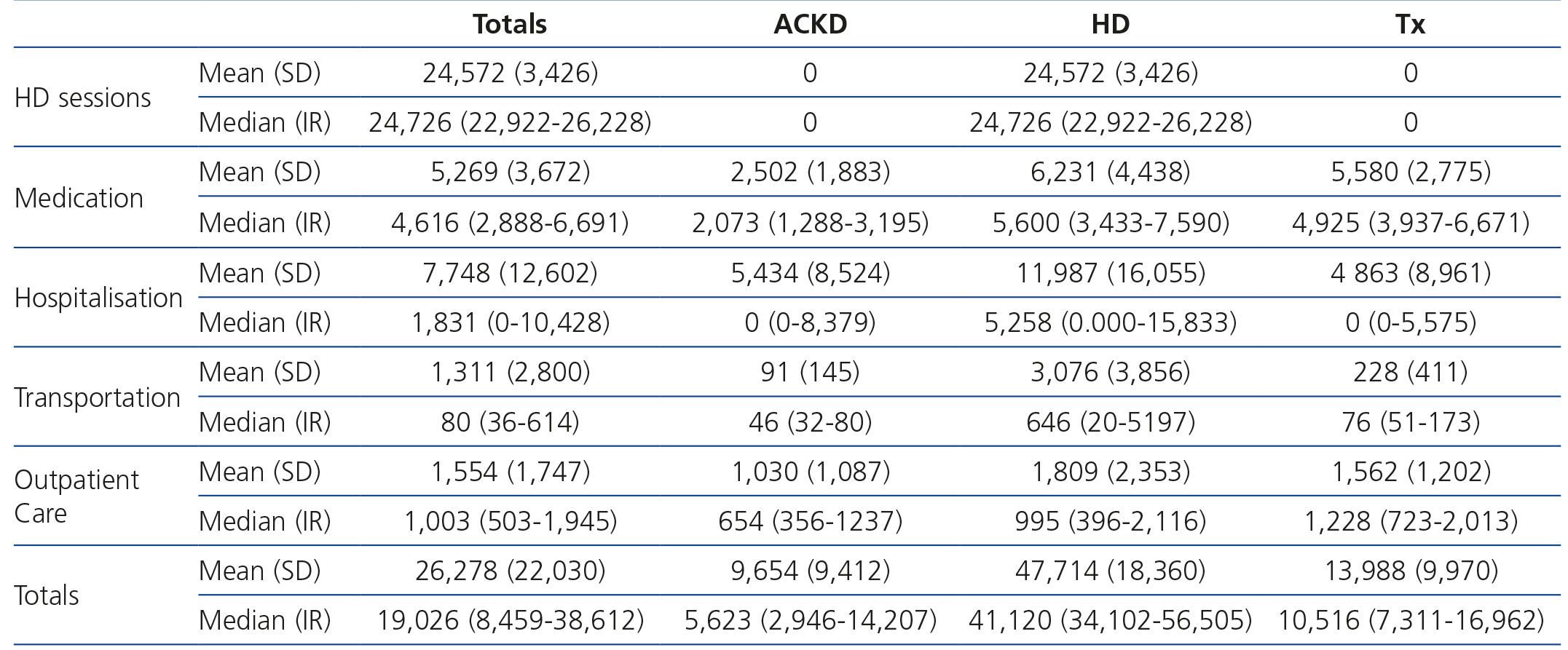

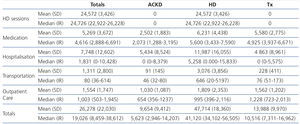

When we analysed the annual cost by treatment method, we found that the greatest financial impact was made by HD, which was more than three times the cost of treatment for transplant patients and almost five times that of ACKD patients. The explanation seems simple: the higher cost is represented by the HD technique, which is not used in transplant patients or ACKD patients. In any case, the cost in HD patients is higher in all financial items. Table 1 displays the mean (SD) and median (IR) of the detailed costs by financial item and treatment method.

Cost of haemodialysis sessions

With the model adopted, the cost of HD sessions was practically identical for all patients according to the subsidised hospital, independently of comorbidity, sociocultural status or location of residence. Differences were only observed in the small proportion of patients who received more than three sessions per week. This cost, as we have mentioned before, is combined in a reimbursement stipulated by the SCS. The average patient/year cost was almost €25,000 (Table 1).

Medication costs

The medication costs by treatment method also showed the highest expense to be in HD, followed very closely by transplantation, while this financial item in ACKD is less than half the cost of that of the other methods (Table 1).

Hospitalisation costs

The financial impact of hospitalisation is less that it may have seemed a priori. This is due to the considerable proportion of patients not being admitted, which thus reduces the mean cost. Again, the highest financial impact was caused by HD, which on average was double the cost of that of patients with ACKD or transplant patients (Table 1). The proportion of patients who were admitted at least once was also maintained according to methods: 68% of HD patients were admitted one or more times, while this was only true of 41% and 40% of patients with ACKD and transplant patients, respectively. If we only consider the costs of those who were hospitalised at least once, the financial impact per treatment method is considerably diminished: ACKD €13,339±€8,539, HD €17,655±€16,726 and transplantation €12,193±€10,604.

Outpatient care

Costs for outpatient care are not very high and not as disparate between methods, representing an average of €1,000-€1,800 per year per patient.

Transportation

The financial impact of transportation is minimal in ACKD and transplant patients, while it is €3,000 in HD, since these patients need to travel three times a week. This amount represents 6% of the total cost of treatment and 12.5% of the cost of HD.

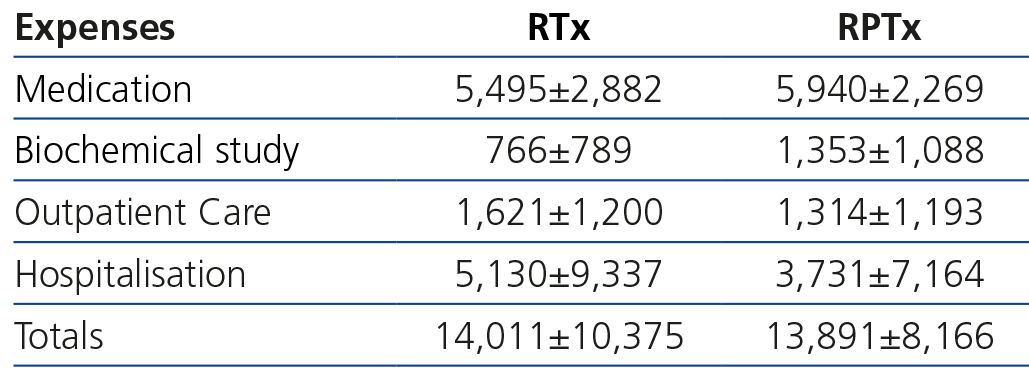

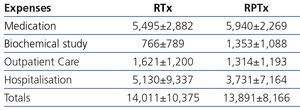

Costs by renal transplantation method

Table 2 shows that the overall and detailed costs of a year of treatment, from six months after transplantation onwards, were not significantly different between RTx and RPTx.

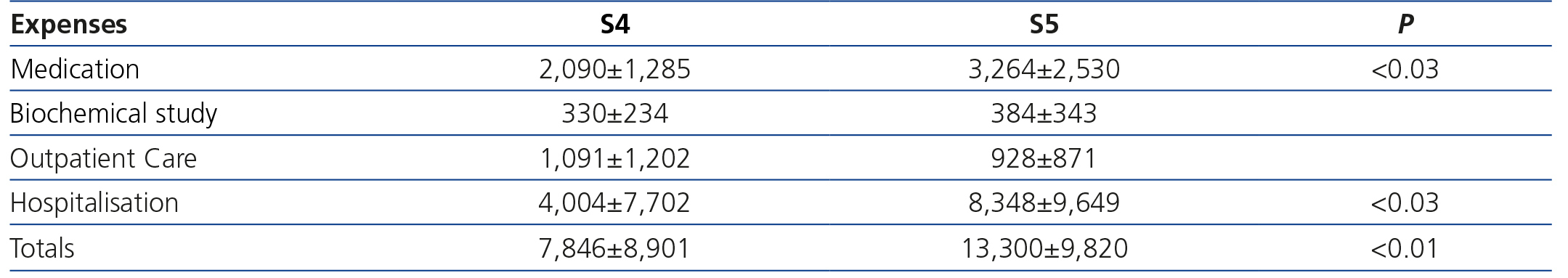

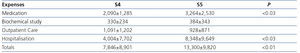

Costs by advanced chronic kidney disease stage

In this section, we observed major differences in terms of costs and the degree of renal damage (Table 3). Expenses for S5 patients were significantly higher than those for S4 patients, particularly in terms of medication and hospitalisation. That said, they continue to be around 30% lower than those observed in HD, and similar to those attributed to transplant patients.

Association between cost and sociocultural parameters

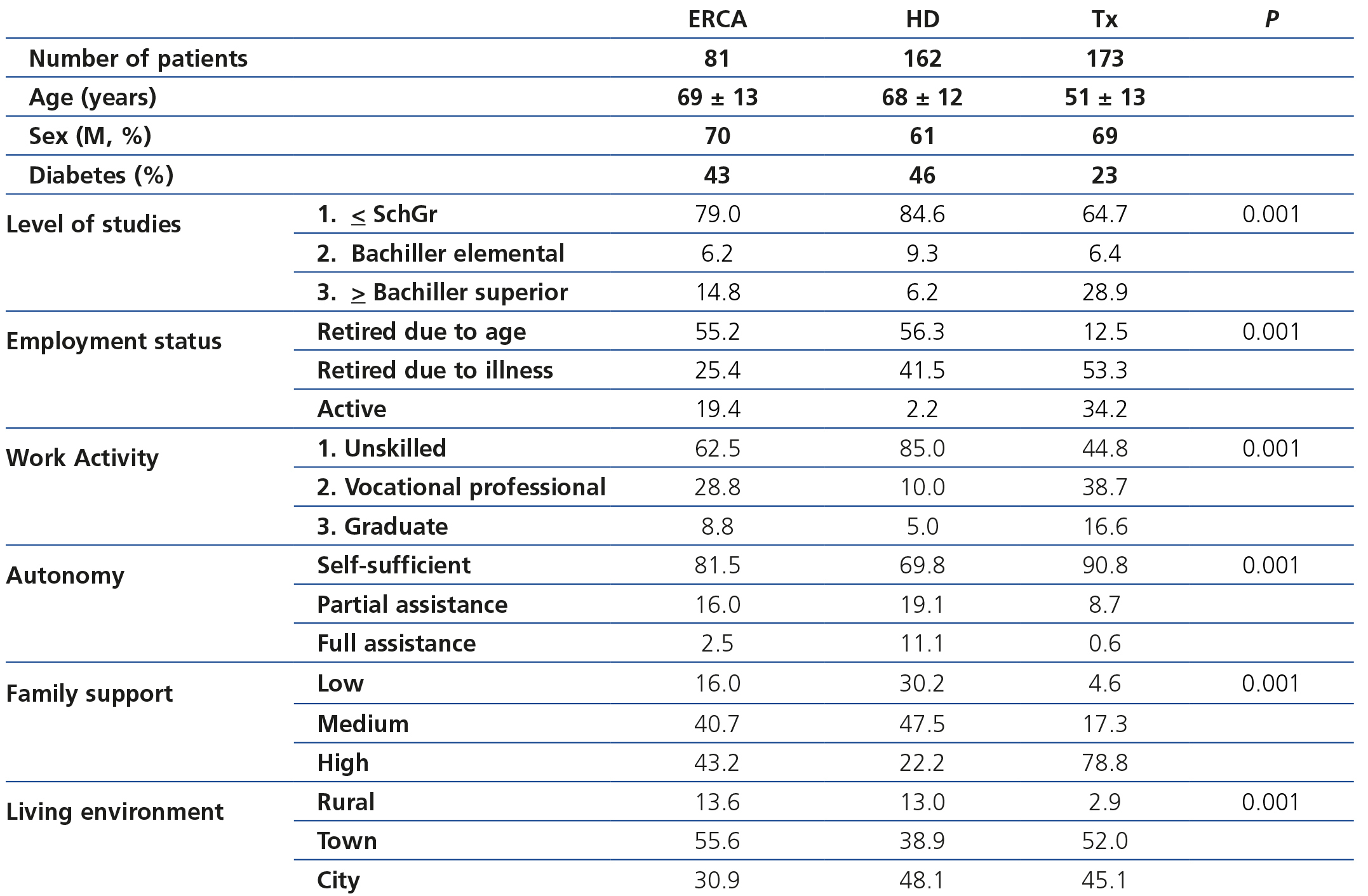

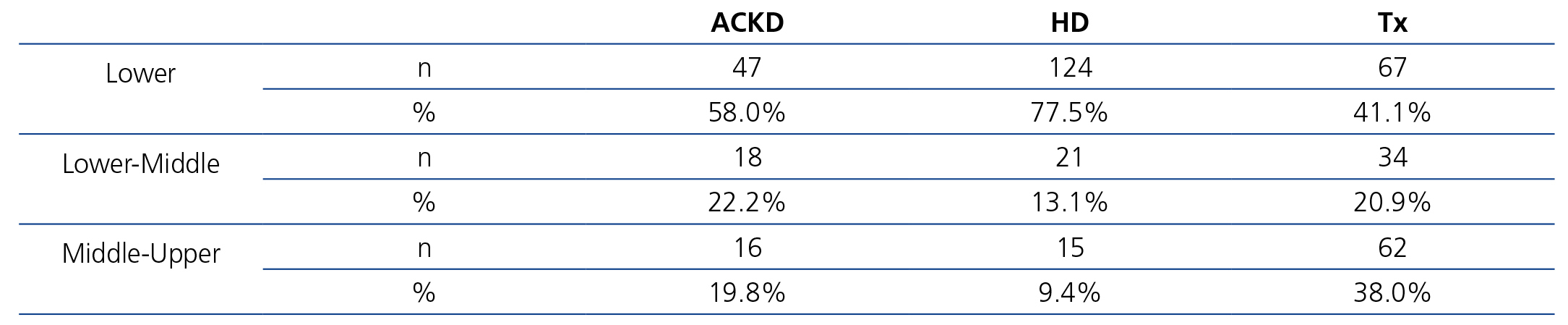

Table 4 displays sociodemographic data by treatment method. It shows that the degree of sociocultural deprivation is considerable; this is defined as the group of circumstances that are an obstacle to normal access to healthcare for people who live in cultural and material poverty.

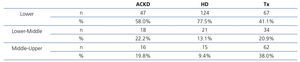

As such, we observed that transplant patients had a better sociocultural position, while those on HD had a worse profile. Around 85% of HD patients had not graduated from school and had an unskilled job. Likewise, this analysis also showed that autonomy and family support are parallel to sociocultural level and, thus, they were higher in the transplant population. In any case, in the transplant population, 65% of patients had not graduated from school (Table 5). The ACKD population had an intermediate profile. Overall, the lower sociocultural profile, as can be imagined, was more apparent in rural areas or towns.

When we analysed the detailed costs in the three sociocultural groups, no relevant differences were found, even when they were classified by treatment method. The transportation expense was lower in patients of a higher sociocultural level, which shows that they more frequently use their own means.

DISCUSSION

In this study, for the first time, we analysed the costs of treatment of patients with S4 and S5 ACKD and RTx and RPTx patients for a specific region, using individual data and not overall budgets. As authors, we are aware that the allocations to the different financial items are difficult to extrapolate given variations in cost in the different regions and the sudden budgetary changes that occur. However, the proportional analysis of each item and each treatment method may be useful.

The greatest obstacle in carrying out the study was the impossibility of including PD, with the latter being a cost-effective alternative for the sustainability of RRT21-23. At the start of the study, the number of patients in our hospital was low and although the incident rate grew, we quickly lost the technique due to transplantation or due to the temporary or definitive change to HD. Since we were not able to increase the number of patients followed-up in time, we ceased to analyse this treatment method. In general, the European series estimate that the cost of PD is between the wide range of 30%-70% less than that of HD13,22,24, which means that it is close to RTx costs. However, a recent article by Lamas Barreiro25 questions the allocation of costs, reopening the debate on the financial advantages of PD. In fact, the incorporation of biocompatible supplements, polyglucose or automation raises its price even above that of HD4.

Cost of renal replacement therapy by treatment methods

Table 1 highlights that HD patients cost was almost five times greater than that of ACKD and more than three times greater than that of transplantation. A more detailed analysis by financial items showed us that HD is mainly more expensive due to the cost of HD sessions, but it is also more expensive in all financial items, particularly that of hospitalisation, in which it is double the costs of the other two methods. However, the hospitalisation cost of transplant patients is very similar to that of ACKD patients.

Classically, RTx has been described as the most efficient treatment option with the lowest cost from the second year onwards. However, our data show that the financial advantages of transplantation are detected at least after six months. Haller et al.13 recently published a cost analysis in Austria that was similar to ours. Despite being countries with different structures and socioeconomic circumstances, the costs during the second year of treatment were slightly lower than in our study for HD (mean±SD: 40,000±10,900 vs. 47,700±18,400) and somewhat higher for RTx (17,200±13,000 vs. 14,000±10,000).

In the transplantation section, the costs between the two methods (RTx and RPTx) were not majorly different, suggesting that RPTx does not entail a higher cost from the sixth month onwards. Unfortunately, there are no other studies that allow us to make comparisons.

With regard to ACKD patients in Spain, no data have been published, and as such, ours may be a new precedent for epidemiological estimation of this cost. According to the results of the Spanish EPIRCE study2, S4 and S5 CKD prevalence is 0.27% (118,800 individuals) and 0.03% (13,200 individuals), respectively. Given these data and the annual cost taken from our study, we can infer that, in the event that all of these patients were detected and monitored in an ACKD clinic, the annual financial amount for managing this population in Spain would be no less than 1108 million euros. Recently in the United States, Honeycutt et al.26 carried out a macroepidemiological ACKD cost analysis. Annual costs were $1,700 for patients in S2, $3,500 for S3 patients and $12,700 (around €10,000) for S4 patients, which demonstrates the major increase in cost as the disease worsens. In our series we also confirmed that, the greater the renal damage, the greater the expense. The cost increased 59% between S4 and S5 (from €7,846 to €13,300), and the greatest increase was observed in medication and hospitalisation costs. It is notable that, in spite of the enormous disparity between health systems, the S4 cost in our series was only 20% higher than that published by Honeycutt et al.26.

The costs of the lower financial impact sections (transportation and outpatient care) were also greater for HD patients. The only clear difference between transplant and ACKD patients was in the medication section, where the transplant patient costs were double the ACKD patient costs.

Treatment with haemodialysis

Allocating expenses attributable to HD is a complicated issue. Most countries with structured public health services pay HD costs, with a standard price per session being assigned and minimum quality criteria being imposed. In general, Spanish health services have adopted this model, including the SCS. However, even within this model there is variability in the options, depending on the hospital and the type of subsidising4.

Some Spanish studies have gone further in addressing the cost of HD, demonstrating that, although they were carried out more than a decade ago, the costs did not differ significantly from current costs27,28. In 2008, Parra Moncasi et al.8 carried out a detailed study on the cost of HD in public and subsidised hospitals. The subsidised hospital cost was €32,872-€35,294, and it was 23% higher in public centres. These costs are approximately 33% higher than those reimbursed by the SCS, but they include expenses that we allocate to other areas (dialysis and outpatient medication, imaging diagnostics and transportation), which represent 40% of the cost in the study by Parra Moncasi8. Therefore, we must assume that the reimbursement by the SCS for HD is quite close to the real costs obtained by these authors8.

Outside our country, a Canadian study10 published in 2002 reported an overall annual HD cost in hospitals of €43,528 (95% confidence interval [CI] €40,528-€46,600) (dollar-euro conversion: €0.85 = 1 American dollar). The cost analysis was carried out with categories that were similar to our own, although the price of the doctor was included under a different heading. Specifically, the cost of HD was €22,688. In spite of the innumerable differences between healthcare models and structures, the specific cost of HD and its proportion of the overall cost of treatment were similar to our study. Moreover, other European studies, methodologically different, reported an HD treatment cost that covered a wide range between €20,000-€80,000/patient/year29,30. Our costs are somewhere near the middle of this range, but unfortunately a more in-depth comparison is impossible with the information available to us. More recently, Icks et al.31 published a study on the overall cost of HD in 2006 in a region of Germany, analysing similar cost components to ours. The overall mean cost was €54,777/patient/year, that is, 15% higher than in our study, fundamentally due to the HD procedure (€30,029/patient/year).

Hospital HD may considerably increase the cost, with around €200 being allocated per session32, which results in an even greater increase in the HD patient cost.

Medication expenses

The medication expenses item was the third largest by percentage, representing 13% of the total. We must highlight that the medication expense has fallen significantly in the last few years, because of cuts generated by the financial crisis in Spain. In our previous study7 the mean HD cost was €12,000 and in the current study, it is €6,000, i.e., half that of the previous study. ESA account for 35% the medication expense in HD. In the previous study, we allocated a cost of around €11 for every 1,000 units of erythropoietin, whereas in the current study, it was €2.4, and it has subsequently continued to decrease. Given that their use is almost universal and the doses are within a narrow range for most patients, the medication expense is quite homogenous in the HD population.

The medication expense in ACKD was less than half that in HD or transplantation. In 2002, Pons et al.30 published a study of the medication costs in HD patients. The expense per patient/year was €3,084 for S4 patients and up to €4,224 for S5 patients, with ESA being responsible for 46.5% of these costs. These values are clearly higher than those recorded in the study that we carried out seven years later: €2,090 and €3,264, respectively, which illustrates the downward adjustment of the prices in recent years. The decrease in the cost of ESA is also explained mainly by the decreased medication cost in this population.

In contrast to the decreased medication cost, particularly due to the lowering of ESA prices, medication expense has probably been the item with the greatest annual increase on previous years, due to the incorporation into the market of more expensive drugs, all related to mineral metabolism: new phosphate binders, vitamin D receptor activators, calcimimetics, etc. A patient who received three of these products with a mean dose may account for an expense of €25-30/day, i.e., an approximate increase of 70%-80% on the overall daily medication cost.

Unfortunately, these financial approximations do not help us much in carrying out future estimations for medication. The imminent arrival of generic drugs to manage mineral metabolism, the continuous downward re-negotiation of prices and reductions or extensive regional competition result in a margin of uncertainty that is impossible to predict.

Hospitalisation expenses

As with our previous publication7, we used the concept of DRG to report hospitalisation costs. This tool should be used as a reference and comparison framework in evaluating the quality of healthcare and the use of services provided by the hospitals. This system was developed by the government in order to establish a payment system for hospitals in the United States. It is based on a fixed quantity according to the specific DRG for each patient treated. The classification was carried out using international classification of disease codes (ICD-10)19. The aim of this classification was to group diseases in order to assign a monetary value to each one, with the objective of improving hospital expense management.

Although this method provides interesting information, unfortunately we do not have comparative data in the national setting for any RRT method, and we cannot guarantee that the coding of data taken from medical records is accurate to the real situation. We are only capable of carrying out comparisons in terms of hospitalisation rates and HD. The study published by Ploth et al.11 shows hospitalisation rates that are almost equivalent to ours: 32% of patients did not require hospitalisation during the study year. However, hospitalisation days vary a lot between different series: the shortest average was reported by Ploth et al.11: 5.7 days; in the series by Sehgal et al.33, it increases to two weeks per patient per year; while in our study it was 18.7 days. However, there is nothing to indicate that these may be reference parameters, given the variability in circumstances that influence healthcare in each region or hospital. In fact, we did not observe a relationship between expenses, time and days hospitalised and initial patient comorbidity and this was probably due to socio-family circumstances or those related to different kinds of health deficiencies that lead to admissions or extended hospitalisation not explained strictly by medical reasons.

Outpatient care

The poor representation of outpatient costs reflects the lead role that nephrologists play in overall patient care, basically becoming the patients’ GPs. Furthermore, analysis of this aspect (consultations, complementary tests) shows enormous variability, given the social and health insecurity of patients in our setting, along with the alarming delays in appointments for studies and consultations, added to the difficulty of travel and family support, etc.

The relationship between the cost of treatment, sociocultural factors and equal opportunities

The association between sociocultural factors and cost is very difficult to establish, particularly in a chronic disease population that is elderly and has major comorbidities. In previous studies7,35, the cost of treatment was not clearly associated with comorbidity ranges or with the group of variables associated with sociocultural deprivation. This is not surprising given that elderly patients, almost all of whom retired early, not having attended school and having worked in unskilled jobs had the most precarious health. But we must insist that, contrarily to what was expected (at least by the authors), none of these factors were associated with the cost of treatment. However, this statement warrants a response: the study population was very homogeneous in terms of sociocultural parameters, including comorbidity. Table 4 eloquently illustrates that more than two thirds of patients did not complete school and their work activity was unskilled. This may explain the lack of association between these parameters and cost. Very extensive series may be required, which include a more diverse population, in order to observe the effect of sociocultural deprivation on costs; although in studies carried out in the United States, we observed that the association between sociocultural factors and costs was weak in dialysis patients36.

With regard to sociocultural status and access to transplantation, two extensive North American studies37,38 reported that the most disadvantaged minorities had fewer opportunities to receive a transplant, with a certain inequality being observed in access to these programmes. In our case, we also observed that patients who received a transplant had the best sociocultural profile and that those who were on HD had the worst profile, with the profile being intermediate in ACKD patients.

A priori, we must explain that patients on the transplant waiting list were younger and had better economic and cultural opportunities. With the aim of explaining this aspect, we carried out a logistic regression using sociocultural status as a dependent variable in a dichotomous format (sociocultural level: lower and middle-upper) and adjusting for age. It is interesting that the relative risk of the HD group was (odds ratio [95% CI]) 3.4 (2.0-6.1), p=.002 times greater than in the transplant group. When we created a matrix table that only included patients younger than 65 years of age (to homogenise the age of the groups), we also observed that transplant patients had a better sociocultural environment than HD patients of a similar age segment (X=19.2, p<.001).

Study limitations

Our study has limitations that we cannot avoid. Firstly, the data obtained from interviews are not strictly accurate or verifiable. Assuming this limitation, the surveys employed were validated and used previously35,39, although with slight modifications in order to adapt them to the situation of HD patients. The study population was not necessarily representative of the national mean; although in age and distribution by sex it was similar, the proportion of diabetic patients was significantly higher and the sociocultural environment probably has considerable interregional differences.

The information obtained about the cost of treatment will be difficult to extrapolate to other regions and populations in absolute terms. The costs assigned to the different expense sections undoubtedly vary between health services and there is enormous variability in the allocation of expenses in different hospitals. Furthermore, we should bear in mind the cost reduction that there has been in some budgetary items, particularly in medication. But it continues to be very useful to have information about the costs between treatment methods or between different budget allocation items. In fact, we consider that the detailed information by cost component may be used as a reference for future studies or to carry out epidemiological estimations.

PD, despite its limitations, has demonstrated cost-effective advantages compared to HD21,23. Unfortunately, in our study, we did not manage to recruit a minimum number of patients to include this group.

CONCLUSIONS

We proved that the HD method is the most expensive procedure in all financial items, whereas the cost of ACKD patients and transplant patients is substantially lower. The similar cost between RTx and RPTx is notable. Unfortunately, the increase in age of the population that develops end-stage renal disease is a definitive limitation for access to transplantation. With these premises in mind, action at an earlier age is vital for preventing prolonged exposure to the adverse effects of chronic diseases, particularly diabetes40,41. In this regard, we should aim to save financially by preventing kidney disease, both in primary care and in specific ACKD clinics. When patients reach advanced stages of the disease, early transplantation, giving full prominence to the living donor programme, must be an initiative that we must drive forward. Lastly, in spite of the health system in Spain being universal and supposedly egalitarian, this analysis invites us to think about whether a lower sociocultural status may undermine opportunities for access to renal transplantation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Detailed costs by financial item and treatment method

Table 2. Detailed costs by financial item and type of transplantation

Table 3. Detailed costs by financial item and advanced chronic kidney disease stage

Table 4. Sociodemographic data by treatment method

Table 5. Renal replacement therapy method and sociocultural status.