To the Editor:

Obesity, defined by a body mass index (BMI)> 30 kg/m2, is a global public health problem, on an epidemic scale. The prevalence of obesity in the Spanish adult population (25 years-60 years) is 14.5%, while the figure for overweight is 38.5% and it increases each year. Obesity is associated with other cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure (HBP), insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidaemia and coronary disease, and can lead to progressive renal failure (RF). RF associated with obesity is a glomerulopathy with variable proteinuria and histopathological findings of focal segmental glomerulonephritis.1 Currently, the treatment for obesity includes bariatric surgery when the ponderal target is not achieved with medical treatment, and even in RF associated with obesity. But it is not an innocuous surgical procedure and can cause RF per se.2 We report two cases of acute renal failure (ARF) following bariatric surgery, recorded at our service.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

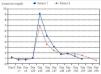

A 60-year-old male with a history of morbid obesity (BMI 47kg/m2), high blood pressure, type 2 DM, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS), hypercholesterolaemia and acute myocardial infarction ischaemic heart disease was treated with 2 stents after percutaneous-stent transluminal coronary angioplasty. He was transferred to the Surgery department for bariatric surgery, using the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy technique. At discharge, he was treated with 10mg/24 hour ramipril, 10/25mg/24 hour bisoprolol/hydrochlorothiazide, 10mg/24 hour atorvastatin, 20mg/24 hour barnidipine and 1/8 hour metformin. After surgery, the patient reported low intake of food and water, occasional episodes of dizziness and loss of 20kg in a month. Given his progressive deteriorating clinical profile and the association with diarrhoea, he was admitted to the Emergency department, where general poor condition, bradypsychia, dry skin, mucous membranes and blood pressure (BP) of 92/65mmHg were observed. Tests were performed: glucose 214mg/dl, urea 403mg/dl, creatinine (Cr) 9.2mg/dl, Na 151mmol/l, Cl 113mmol/l, K 4mmol/l; Complete blood count: haemoglobin (Hb) 15.4g/dl, VH 44.5%, leukocytes 18,800/ul; platelets 287,000/ul; renal function in urine: urea 239mg/dl, Cr 339mg/dl, Na 52mmol/l, K 9.1mmol/l, fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) 0.9%; venous blood gases: pH 7.33, bicarbonate 11.1mmol/l, pCO2 21mmHg. He was transferred to the Nephrology department with the diagnosis of with prerenal ARF, hypernatraemia and urinary tract infection. Antibiotic treatment and controlled electrolyte replacement was initiated with good response, with creatinine levels of 0.86mg/dl at discharge (Figure 1).

Case 2

A 44-year-old woman with the following history: ex-smoker, HBP, type 2 DM, morbid obesity (BMI 59.19kg/m2), cholecystectomy, appendectomy, umbilical hernia and caesarean section. She was referred to General Surgery for bariatric surgery using the Larrad technique. She came to the Emergency department two months after surgery, complaining of repeated postprandial vomiting since discharge and syncope. In the physical examination, poor general condition, signs of salt and water depletion, BP 66/48 and CVP 4 cc H2O were observed. A test was performed: urea 284mg/dl, Cr 6.98mg/dl, Na 119mmol/l, K 2.4mmol/l, Cl 65mmol/l, Pcr 4.8mg/dl, lactate 4.7mmol/l, osmolarity 333mOsm/kg; complete blood count: Hb 14.2g/dl, VH 42%; leukocytes 19,000/ul; platelets 251,000/ul; venous blood gases: pH 7.49, bicarbonate 25.9mmol/l, pCO2 34mmHg; renal function in urine: FENa 0.11%, urea 276mg/dl, Cr 274.8mg/dl, Na 5mmol/l, K 15.4mmol/l. She was admitted to the Nephrology department with diagnosis of prerenal ARF secondary to volume depletion, hyponatraemia and hypokalaemia. She started on salt and water replacement and progressive electrolytic correction with improvement of renal function, until normalisation (Figure 1). During hospitalisation, the patient developed respiratory failure and septic shock secondary to respiratory infection. She was transferred to the intensive care unit and died after two months.

DISCUSSION

The treatment of morbid obesity includes: a) diet and modification of lifestyle, b) pharmacotherapy and c) bariatric surgery.2 Bariatric surgery is indicated in patients with BMI ≥40kg/m2 in whom treatment with diet and exercise, associated or not with drug treatment, is not effective and in patients with BMI>35kg/m2 and obesity-related comorbidities such as HBP, glucose intolerance, DM, dyslipidaemia, or OSAS.

Bariatric surgery has high morbidity and its mean mortality rate at 30 days is 1%. Surgical techniques are divided into restrictive, malabsorptive and mixed. The complications are different according to the surgical technique employed. Early complications of bariatric surgery are bleeding, perforation, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism and pulmonary and cardiovascular complications, while late complications include cholelithiasis, malnutrition and neurological and psychiatric complications. Although bariatric surgery is an effective treatment for obesity and is even one form of treatment for associated RF, it may result in ARF3 and very severe, life-threatening water-electrolyte imbalances, especially when the surgical technique used is the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or a jejunoileal bypass. RF aetiology may be dehydration secondary to diarrhoea and/or vomiting4 or ARF due to intratubular calcium oxalate crystal deposition. ARF usually appears a month after bariatric surgery and is characterised by high creatinine levels in relation to the patient’s weight. The absence of nephrocalcinosis and urolithiasis and the fact that the ARF may have been prerenal and not parenchymal allowed us to rule out the diagnosis of ARF due to intratubular calcium oxalate crystal deposition. The treatment includes progressive hydration and correction of electrolyte abnormalities, haemodialysis in cases of established ARF and even conversion of the surgical technique employed in cases of oxalate-induced nephropathy.3,4

In conclusion, bariatric surgery is part of the therapeutic arsenal for obesity, but it is not without risks. Patients should be followed closely after surgery, with early referral to Nephrology if there is renal function deterioration, since it is a reversible form of RF if treated early, or the appearance of electrolyte disturbances that may put the patient’s life at risk.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Creatinine progression (mg/dl) after bariatric surgery