To the Editor,

Infections continue to be the main problem in peritoneal dialysis (PD). The percentage of gram-positive peritonitis has decreased in recent years as the connection systems have improved. However, gram-negative peritonitis has not changed. Preventing exit site infections (ESI) is crucially important for preventing this type of complication.1

There are studies that show that topical gentamicin is more effective than mupirocin at reducing Pseudomonas infections, and as effective at reducing Staphylococcus aureus infections. Furthermore, there are studies that warn us about mupirocin-resistant S. aureus developing.2

Topical gentamicin does not have many secondary effects. The most important ones are Candida infections, which are generally resolved with oral antifungal treatment with no major consequences.3 Meanwhile, systemic absorption of topical gentamicin at 0.1% is 2% or less.4

We conducted a retrospective study of all types of peritonitis and ESI that occurred in our unit from January 2008 to June 2011.

In January 2009 we decided to change the protocol for treating peritoneal catheter ESI, applying topical gentamicin once a day, with the aim of reducing the incidence of gram-negative peritonitis.

Before changing the protocol, samples were taken from the exudate at the catheter exit site of 44 patients, but no acute infection data were presented. Fourteen percent of the cases were colonised due to a gram-negative bacterium.

Percentages of peritonitis infections were:

In 2008 (51 patients): 33 episodes, 51% gram-positive bacteria, 40% gram-negative and 9% negative culture.

In 2009 (49 patients): 32 episodes, 71% gram-positive bacteria, 22% gram-negative and 8% negative culture.

In 2010 (43 patients): 24 episodes, 58% gram-positive, 29% gram-negative and 13% negative culture.

In 2011 (43 patients), 5-month follow-up: 11 episodes, 90% gram-positive and 10% gram-negative.

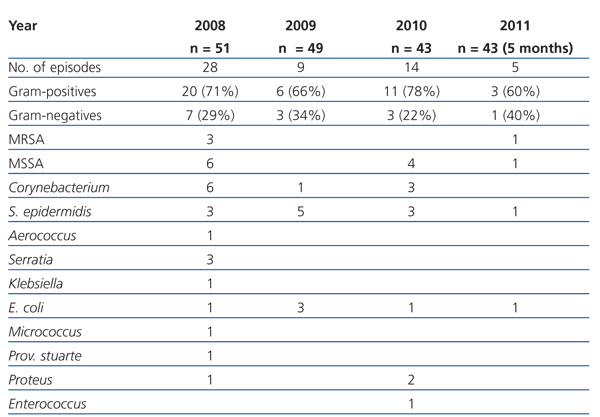

The percentages and bacteria responsible for ESI are shown in Table 1.

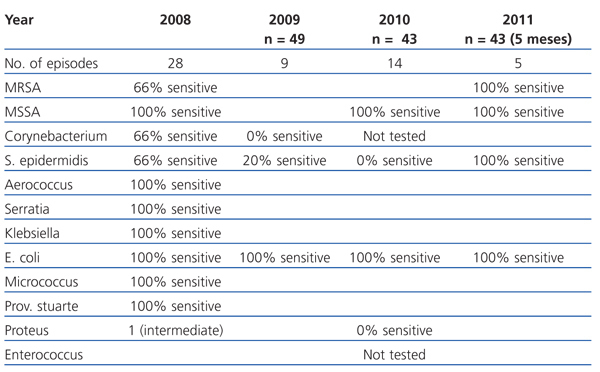

We assessed the gentamicin-sensitivity of bacteria responsible for ESI during the study period. The results are shown in Table 2.

None of the patients presented with fungal infections in the exit site or any other effect that was secondary to topical treatment during the study period.

The percentage of gram-negative peritonitis reduced considerably once the protocol had changed to treat the exit site. Gentamicin probably does not influence the incidence of gram-negative peritonitis whose source is intestinal contamination, but it is related with pericatheter contamination.

The percentage of gram-negative infections did not decrease after changing the protocol, but the overall incidence of ESI did. We should point out that a significant percentage of gram-negative ESI were because a patient did not regularly treat the exit site.

During the study period, we did not observe a significant increase in bacteria being resistant to gentamicin, except in the case of S.epidermidis, which presented an elevated resistance during 2009-2010. Only one case occurred due to this bacterium in 2011, which was sensitive to said antibiotics.

To conclude, the use of topical gentamicin to treat the peritoneal catheter exit site could be a good therapeutic measure to prevent ESI and peritonitis. Furthermore, in our sample it was not associated with increased resistance during a 29-month follow-up period, or with any other secondary effect.

Table 1. Evolution of bacteria causing exit site infections

Table 2. Sensitivity of infection-causing bacteria to treatment prescribed