Acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy is a type of renal injury characterized by the presence of inflammatory infiltrates, edema, and tubulitis in the interstitial compartment, and it is often accompanied by acute failure.1 It represents the third most frequent cause of acute renal function impairment in hospitalized patients,2 with an incidence of 5–27% in renal biopsies performed for diagnosis of acute renal failure.3,4 Its course may be subclinical or it may present progressive deterioration evolving into chronic renal failure. Its etiology is diverse, with immunoallergic reaction to drugs being the most frequent cause, with a prevalence of approximately 60–70%.5

We present the clinical case of a patient with a pathological diagnosis of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis with hyaline arteriopathy secondary to treatment with statins.

The patient is a 69-year-old woman with a personal history of vascular risk factors: high blood pressure, mixed dyslipidemia on treatment with pravastatin, and ischemic heart disease that require a stent. She came to the emergency room with symptoms of asthenia, vomiting, and low blood pressure. These symptoms were accompanied by foamy urine with preserved diuresis, without dark urine or hematuria, of approximately two months' duration. Laboratory tests showed acute deterioration of renal function with creatinine 6.82 mg/dl (previously preserved renal function), metabolic acidosis (pH 7.28 with HCO3 15.5 mmol/l), hemoglobin 9.1 g/dl, and eosinophilia 7.2%. Finally, it was decided to admit her to the Nephrology department for study due to non-oliguric acute renal failure refractory to initial medical treatment and observation.

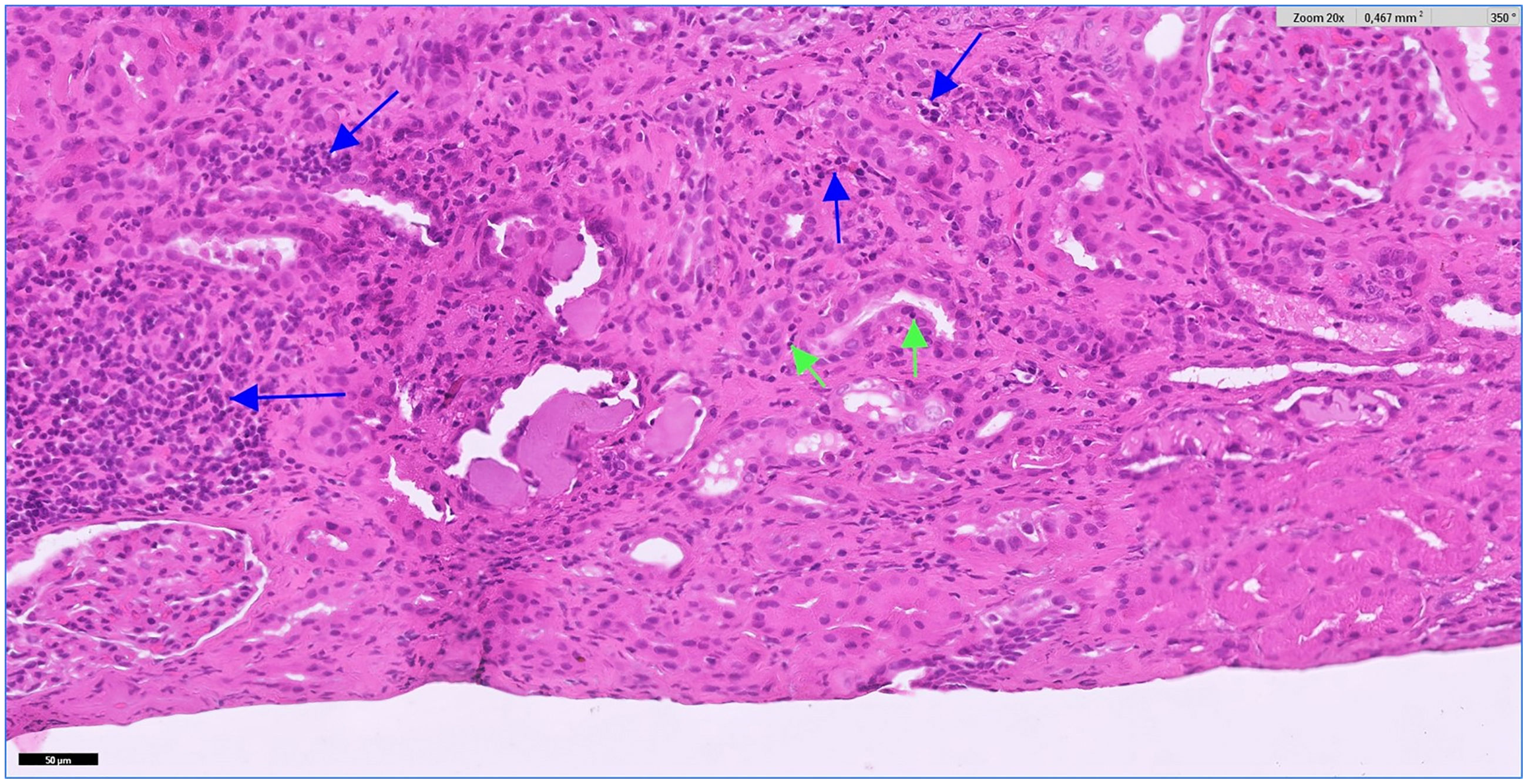

Due to the suspicion of a possible systemic disease with renal involvement, a study of secondary causes was performed, highlighting a normal autoimmune profile except for the presence of positive ANA values (ANA 1/320, homogeneous pattern). Regarding the rest of the complementary tests, the proteinogram, immunoglobulins and complement were within normal range, as well as negative viral serologies. A renal ultrasound was performed, which reported normal-sized kidneys with preserved cortical thickness without urinary tract dilation. It was decided to administer 3 boluses of methylprednisolone 250 mg for the treatment of a probable acute interstitial nephropathy, with adequate renal response in the first 48 h after starting corticosteroid treatment (creatinine 4.42 mg/dl). Finally, an ultrasound-guided percutaneous renal biopsy was performed with a pathological result (Fig. 1) of evolving tubulointerstitial nephritis (cytoplasmic acidophilia, nuclear pyknosis, loss of the brush border, flattening and detachment of the tubular epithelium) with moderate hyaline arteriopathy. The patient was subsequently discharged with follow-up by Nephrology, presenting stable renal function with creatinine of 3 mg/dl.

Foci of inflammatory infiltrate are observed in the cortex, forming patches and also arranged in a dispersed manner. It is mainly composed of lymphocytes (blue arrows). Focally, the infiltrate affects the tubules (tubulitis) (green arrows). Hematoxylin-eosin ×20. The color of the figures can only be seen in the electronic version of the article.

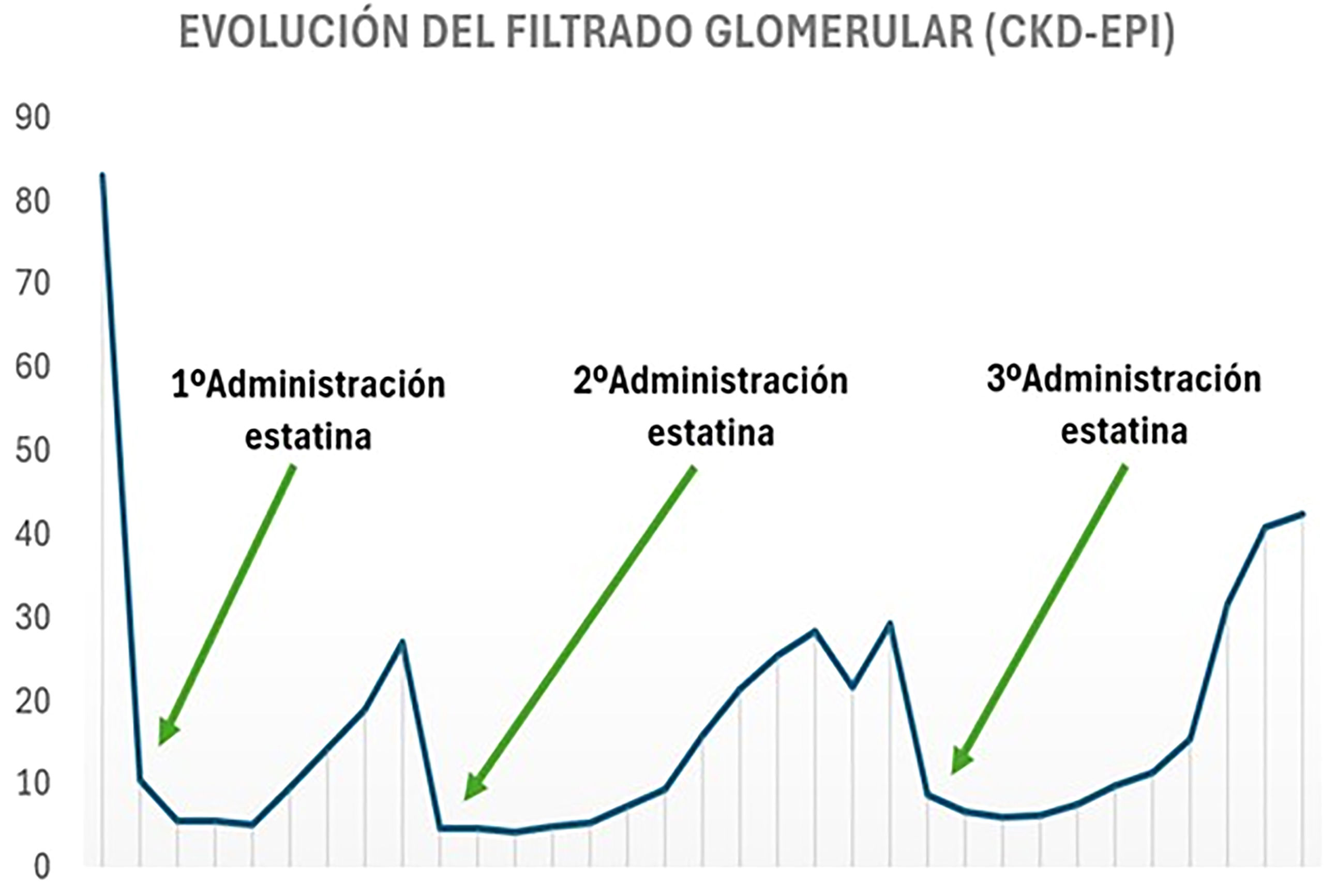

However, the year after hospital admission, the patient again presented two clinical symptoms similar to those of the first admission (Fig. 2). As a novelty, in the second admission she started treatment only with simvastatin/ezetimibe and the third admission she had started treatment with atorvastatin, presenting in addition with the deterioration of renal function a generalized skin rash. Progressive deterioration of renal function was notable (peak creatinine of 8.06 mg/dl). Finally, she responded on all occasions to corticosteroid therapy, thus the cause of acute renal failure in the last two admissions was associated with the use of statins. Allergy study was completed and currently she is being treated with alirocumab, maintaining lipid levels within the range (total cholesterol 145 mg/dl, HDL 49 mg/dl and LDL 38 mg/dl) and the renal function is preserved (creatinine 1.29 mg/dl).

Today, statins are one of the most prescribed drugs for the treatment of dyslipidemia. One of the side effects described in relation to the use of statins is rhabdomyolysis due to myotoxicity in 2–11% of patients,6,7 with the presence of myoglobinuria being attributed to the development of acute interstitial nephritis.8 However, acute interstitial nephropathy is a rare cause of acute renal failure.

The importance of this clinical case lies in the fact that it is essential to ask the patient about the recent medication received, changes in treatment or the introduction of new drugs, since in many cases it is difficult to establish the causal agent of the pathology. It should be taking into account that kidney damage does not always correlate directly with the initiation of the drug and the clinical manifestations can be variable.

Ethical aspectsThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols established in their work center to access the data of the patient's clinical history to be able write this manuscript aiming to be disseminated to the scientific community.

FundingThis research has not received specific financial aid from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.