Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing global health problem, with projections indicating a significant increase in its prevalence. The kidney failure risk equation (KFRE) has emerged as a valuable predictive tool to assess the risk of kidney failure in patients with CKD stages 3–5.

This narrative review presents a comprehensive analysis of the KFRE's development, validation, and clinical applications, and highlights its role in predicting disease progression, guiding nephrology referrals, and planning vascular access creation.

La enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) constituye un problema de salud global en aumento, con proyecciones que indican un incremento significativo en su prevalencia. La Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) ha surgido como una herramienta predictive valiosa para evaluar el riesgo de insuficiencia renal en pacientes con ERC en estadios 3 a 5.

Esta revisión narrativa presenta un análisis exhaustivo sobre el desarrollo, validación y aplicaciones clínicas de la KFRE, y resalta su papel en la predicción de la progresión de la enfermedad, la orientación de las derivaciones a nefrología y la planificación de la creación de accesos vasculares.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health problem which is becoming increasingly prevalent over the years. It is estimated that the global average prevalence of CKD is 13.4%, reflecting its significant impact on the population.1 Recent projections suggest that by 2040, CKD will be the fifth major cause of death globally.2 Additionally, with CKD progression there is a growing need to initiate renal replacement therapy (RRT). In 2005, the number of patients under RRT was 1.9 million, and by 2010, the number had increased to 2618 million patients. These numbers are expected to continue rising, with projections reaching 5439 million patients under RRT by 2030.3,4

Given this data, it is of utmost importance to determine how we can anticipate the progression of CKD and, consequently, adjust the therapy according to each patient's individual risk of progression.

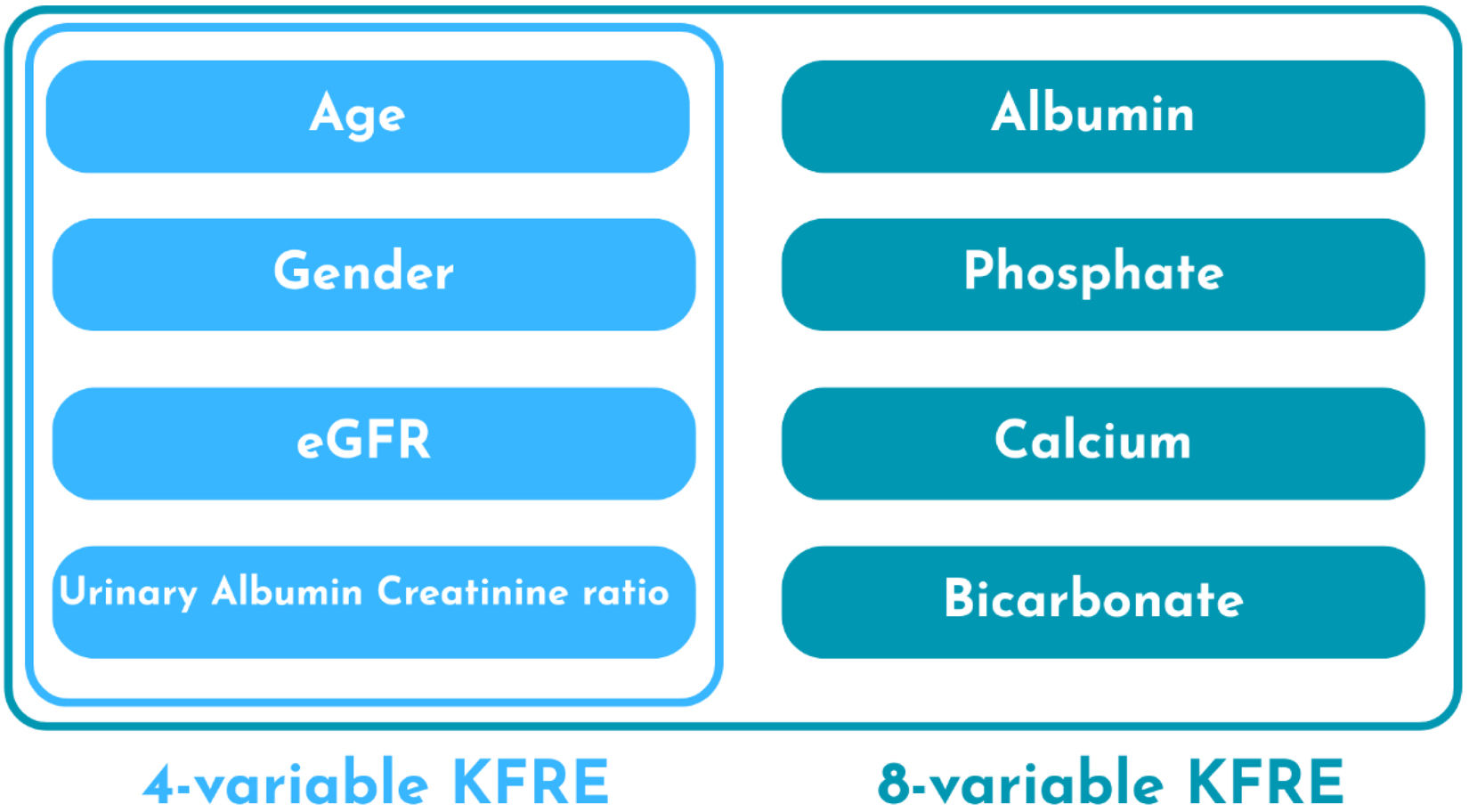

In 2011, the kidney failure risk equation (KFRE) was developed in a retrospective study in Canada.5 It calculates the risk of kidney failure in patients with CKD stages 3–5 and provides a 2- and 5-year risk of kidney failure. The variables used are age, sex, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR). There is also an eight-variable model that incorporates additional laboratory variables, such as serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum bicarbonate, and serum albumin. Subsequently, the KFRE was validated in multiple multinational cohorts, which has contributed to expanding its application in clinical practice.6

The KFRE has been useful to assist in clinical decisions, and the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 guidelines recommend using KFRE not only to guide the referral to nephrology, but also the appropriate timing to start planning for RRT, which includes preparation for vascular access (VA) to haemodialysis (HD) and referral for kidney transplants.7

This narrative review aims to provide a comprehensive summary of the available literature regarding the multiple clinical applications and utility of the KFRE in current medical practice.

MethodsA comprehensive literature search was performed in June 2025 using the PubMed database with the following key concepts: (“Kidney Failure Risk Equation” OR “KFRE” OR “kidney failure prediction model”) AND (“chronic kidney disease” OR “CKD” OR “renal insufficiency” OR “end-stage renal disease” OR “ESRD” OR “kidney failure” OR “renal failure”) AND “development” AND (“validation” OR “external validation”) AND “CKD etiology” AND (“nephrology referral” OR “primary care”) AND (“risk based approach” OR “personalized medicine”) AND (“dialysis planning” OR “vascular access”) AND (“kidney transplant patients” OR “kidney transplant recipients”) AND (“healthcare costs” OR “cost of care”). The search was restricted to observational studies published between 2011 and 2025.

Development of an accurate predictive modelGiven the increasing prevalence of CKD and variability of disease progression, it was crucial to develop an accurate prediction model for the progression to kidney failure.

The KFRE was developed in 2011 through a retrospective study conducted in Canada. The authors aimed to develop and validate a predictive model for CKD progression with routinely measured and easily available variables, to facilitate the implementation of this model in clinical practice. The development and validation populations were defined, both including patients with CKD stages 3–5 at the time of initial referral. The parameters used to create different models included demographic variables (age and sex), physical examination variables (blood pressure and weight), comorbidities (diabetes and hypertension), and laboratory variables (eGFR, serum creatinine, serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum albumin, serum bicarbonate, urine albumin–creatinine ratio). The outcome of interest was kidney failure, defined by the initiation of dialysis or kidney transplantation. Seven predictive models were developed with different conjugations of the variables and ultimately found that the models with four (age, sex, eGFR and ACR) and eight variables (adds serum albumin, serum phosphate, serum calcium and serum bicarbonate) achieved the best results. The four-variable model achieved a high C statistic of 0.910 (95% CI 0.894–0.926) in the development cohort and 0.835 (95% CI 0.819–0.851) in the validation cohort, indicating excellent discriminatory ability. The eight-variable model yielded an even higher C statistic of 0.917 (95% CI 0.901–0.933) in development and 0.841 (95% CI 0.825–0.857) in validation.5 Variables required for calculation of four and eight variables KFRE are depicted in Fig. 1.

The KFRE would be useful throughout CKD progression to individualize patient care. In patients with CKD stage 3, the KFRE can distinguish low-risk patients, who can be managed by primary care, from high-risk patients, who would require nephrology appointments and more intensive intervention.8 In CKD stage 4 patients, the KFRE is useful to indicate the appropriate timing for pre-dialysis interventions, such as dialysis modality education, VA creation, and pre-emptive transplantation. Additionally, in high-risk patients, this tool can also be used to enrol patients in clinical trials. However, despite external validation, the KFRE could not be generalized to all CKD patients worldwide and the authors recommended external validation in diverse CKD cohorts and clinical trials to further evaluate the findings.5

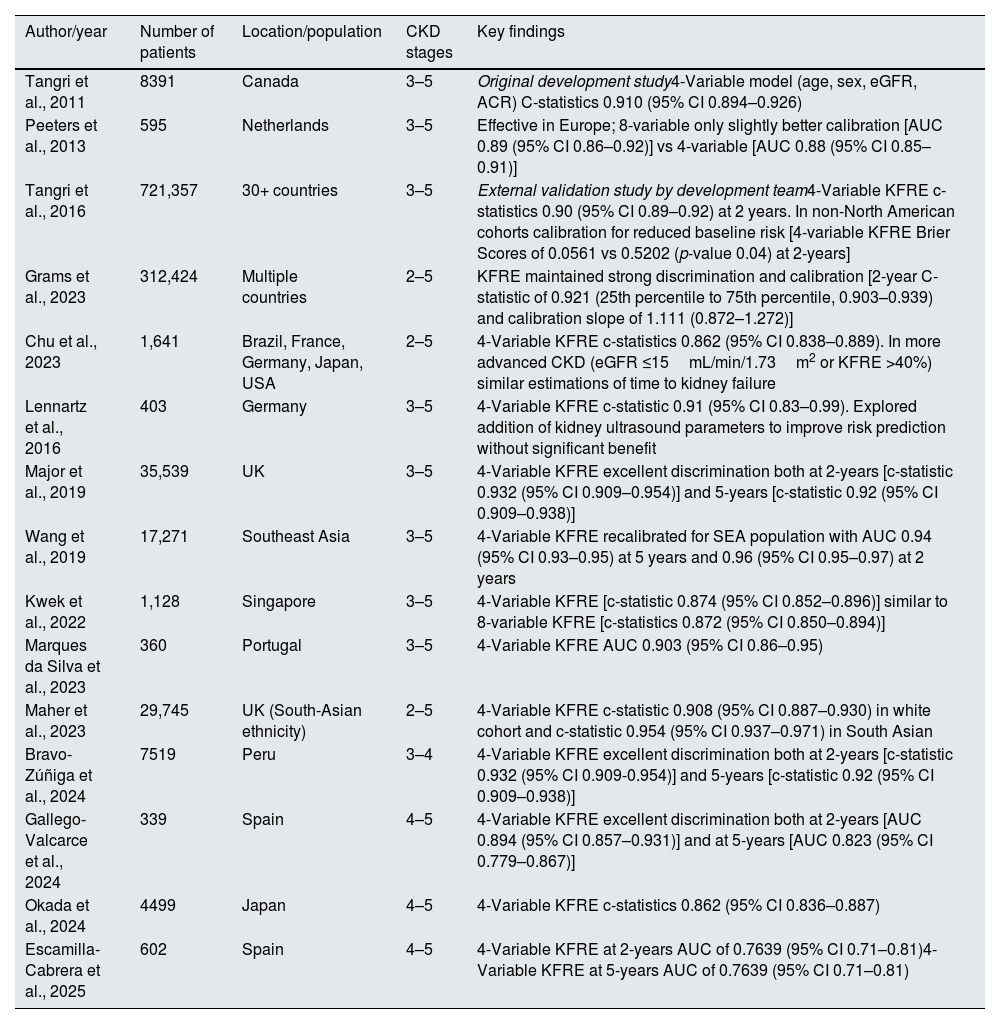

Subsequent validation studies have evaluated the applicability of the KFRE in diverse patient populations, as described in Table 1.

Summary of studies of KFRE development and validation.

| Author/year | Number of patients | Location/population | CKD stages | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangri et al., 2011 | 8391 | Canada | 3–5 | Original development study4-Variable model (age, sex, eGFR, ACR) C-statistics 0.910 (95% CI 0.894–0.926) |

| Peeters et al., 2013 | 595 | Netherlands | 3–5 | Effective in Europe; 8-variable only slightly better calibration [AUC 0.89 (95% CI 0.86–0.92)] vs 4-variable [AUC 0.88 (95% CI 0.85–0.91)] |

| Tangri et al., 2016 | 721,357 | 30+ countries | 3–5 | External validation study by development team4-Variable KFRE c-statistics 0.90 (95% CI 0.89–0.92) at 2 years. In non-North American cohorts calibration for reduced baseline risk [4-variable KFRE Brier Scores of 0.0561 vs 0.5202 (p-value 0.04) at 2-years] |

| Grams et al., 2023 | 312,424 | Multiple countries | 2–5 | KFRE maintained strong discrimination and calibration [2-year C-statistic of 0.921 (25th percentile to 75th percentile, 0.903–0.939) and calibration slope of 1.111 (0.872–1.272)] |

| Chu et al., 2023 | 1,641 | Brazil, France, Germany, Japan, USA | 2–5 | 4-Variable KFRE c-statistics 0.862 (95% CI 0.838–0.889). In more advanced CKD (eGFR ≤15mL/min/1.73m2 or KFRE >40%) similar estimations of time to kidney failure |

| Lennartz et al., 2016 | 403 | Germany | 3–5 | 4-Variable KFRE c-statistic 0.91 (95% CI 0.83–0.99). Explored addition of kidney ultrasound parameters to improve risk prediction without significant benefit |

| Major et al., 2019 | 35,539 | UK | 3–5 | 4-Variable KFRE excellent discrimination both at 2-years [c-statistic 0.932 (95% CI 0.909–0.954)] and 5-years [c-statistic 0.92 (95% CI 0.909–0.938)] |

| Wang et al., 2019 | 17,271 | Southeast Asia | 3–5 | 4-Variable KFRE recalibrated for SEA population with AUC 0.94 (95% CI 0.93–0.95) at 5 years and 0.96 (95% CI 0.95–0.97) at 2 years |

| Kwek et al., 2022 | 1,128 | Singapore | 3–5 | 4-Variable KFRE [c-statistic 0.874 (95% CI 0.852–0.896)] similar to 8-variable KFRE [c-statistics 0.872 (95% CI 0.850–0.894)] |

| Marques da Silva et al., 2023 | 360 | Portugal | 3–5 | 4-Variable KFRE AUC 0.903 (95% CI 0.86–0.95) |

| Maher et al., 2023 | 29,745 | UK (South-Asian ethnicity) | 2–5 | 4-Variable KFRE c-statistic 0.908 (95% CI 0.887–0.930) in white cohort and c-statistic 0.954 (95% CI 0.937–0.971) in South Asian |

| Bravo-Zúñiga et al., 2024 | 7519 | Peru | 3–4 | 4-Variable KFRE excellent discrimination both at 2-years [c-statistic 0.932 (95% CI 0.909-0.954)] and 5-years [c-statistic 0.92 (95% CI 0.909–0.938)] |

| Gallego-Valcarce et al., 2024 | 339 | Spain | 4–5 | 4-Variable KFRE excellent discrimination both at 2-years [AUC 0.894 (95% CI 0.857–0.931)] and at 5-years [AUC 0.823 (95% CI 0.779–0.867)] |

| Okada et al., 2024 | 4499 | Japan | 4–5 | 4-Variable KFRE c-statistics 0.862 (95% CI 0.836–0.887) |

| Escamilla-Cabrera et al., 2025 | 602 | Spain | 4–5 | 4-Variable KFRE at 2-years AUC of 0.7639 (95% CI 0.71–0.81)4-Variable KFRE at 5-years AUC of 0.7639 (95% CI 0.71–0.81) |

UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America.

A European study examined the performance of the three-variable, four-variable, and eight-variable KFRE models in individuals with CKD stages 3–5, finding that the KFRE effectively predicted kidney failure in this cohort. Notably, the eight-variable model exhibited only slightly improved calibration [AUC 0.89 (95% CI 0.86–0.92)] compared to the simpler models [4-variable AUC 0.88 (95% CI 0.85–0.91) and 3-variable 0.88 (95% CI 0.85–0.92)].9

A large multinational validation study assessed the KFRE's performance across 31 cohorts from over 30 countries, involving 721,357 participants with CKD stages 3–5. This analysis revealed that the 4-variable KFRE maintained good discriminatory ability [c-statistics 0.90 (95% CI 0.89–0.92) at 2 years and 0.88 (95% CI 0.86–0.90) at 5 years]. However, the model tended to overestimate risk in some non-North American populations. Subsequent adjustments to the calibration factors, reducing the baseline risk at 2 and 5 years, improved the KFRE's performance in these non-North American settings [4-variable KFRE Brier Scores of 0.0561 vs 0.5202 (p-value 0.04) at 2-years and 0.08935 vs 0.08263 (p-value 0.01) at 5-years].6

Despite the slightly better performance of the eight-variable KFRE, the four-variable model is effective and easier to implement in clinical practice.6,9

Advanced CKD is of particular interest since these are the patients who will need more guidance in terms of therapeutic decisions. Therefore, it is essential to understand how KFRE performs within this population.

A study implemented in a tertiary care centre in Ottawa analysed 1293 patients with advanced CKD – stages 4 and 5 from different aetiologies.10,11 The findings demonstrate that KFRE is a clinically useful prediction tool for progression from CKD to kidney failure [2-year AUC 0.83 (95% CI 0.81–0.85)]. Nevertheless, the predicted risk of kidney failure at 2 and 5 years was slightly higher than the observed risk in all aetiologies except for polycystic kidney disease.11

Further studies backed the clinical usefulness of KFRE in advanced CKD. Two studies compared the performance of eGFR and KFRE in this population. Ali et al., compared the clinical utility of KFRE to eGFR for guiding treatment decisions, such as dialysis planning and transplant preparation. This study revealed that the KFRE had good discrimination [4-variable AUC 0.796 (0.762–0.831)] and provided superior clinical utility compared to multiple eGFR thresholds for identifying patients needing closer monitoring or intervention.10 Chu et al. evaluated the utility of both eGFR and KFRE to estimate the time to kidney failure.12 KFRE had high discrimination [C-statistics 0.862 (95% CI 0.838–0.889)], and higher scores were associated with shorter time to kidney failure. In advanced CKD (eGFR ≤15mL/min/1.73m2 or KFRE >40%), both tools proved similarly consistent time to kidney failure predictions. In a retrospective study, Okada et al. specifically assessed patients with eGFR ≤30mL/min/1.73m2 and demonstrated that adding eGFR slope and changes in urinary proteins could lead to improvement of model discrimination [c-statistics 0.921 (95% CI 0.905–0.938) vs 0.862 (95% CI 0.836–0.887)].13

The influence of age in the KFRE was also considered. A study aimed to assess how age influences the calibration and discrimination of KFRE in patients with advanced CKD and to understand the role of death as a competing risk in prediction accuracy.14 The results showed good discrimination (c-statistics 0.70–0.79) but an overestimation of the risk of kidney failure in patients ≥80 years old compared to other ages.

A more recent study also evaluated the KFRE in different age groups and the impact of the competing risk of death. In patients aged over 65 years, overprediction was observed for five-year risk estimates. After incorporating the competing risk of death in the KFRE, calibration was improved in this group of patients despite not improving the overall model performance.15

Indeed, multiple studies have shown a small overestimation of the risk of kidney failure by KFRE in advanced CKD and older age patients.11,14,15 The fact that the KFRE does not account for the competing risk of death is an important limitation of the risk score in these patients. In these subgroups, understanding the competing risk of death can help clinicians with more accurate prognostic information to help in treatment guidance. Thus, in some cases it might be useful to use another predictive model for kidney failure, such as the Grams model, in patients with more advanced CKD, as it accounts for the competing risk of death with a good discrimination [C-statistic of 0.814 (range 0.680–0.972)].16 In particularly high-risk patients prediction models might have poorer performance and competing events must be considered.17,18

Researchers have also explored whether incorporating changes to some variables could change the KFRE's predictive performance. Grams et al. assessed the KFRE's performance using the updated CKD-EPI 2021 eGFR equation, finding that the KFRE maintained strong discrimination and calibration [2-year C-statistic of 0.921 (25th percentile to 75th percentile, 0.903–0.939) and calibration slope of 1.111 (0.872–1.272)].15 Evaluations of other potential inputs, such as historical eGFR averages, eGFR slope, cardiovascular comorbidities and kidney ultrasound markers, did not yield significant improvements, despite increasing the model's complexity.19

The KFRE model has been extensively validated in multiple cohorts from the UK, Germany, Spain, Portugal, and South Asia, among other places.19–27

Predicting CKD progression in different CKD aetiologiesCKD has a variety of possible aetiologies, and its progression may differ depending on the underlying disease mechanism.

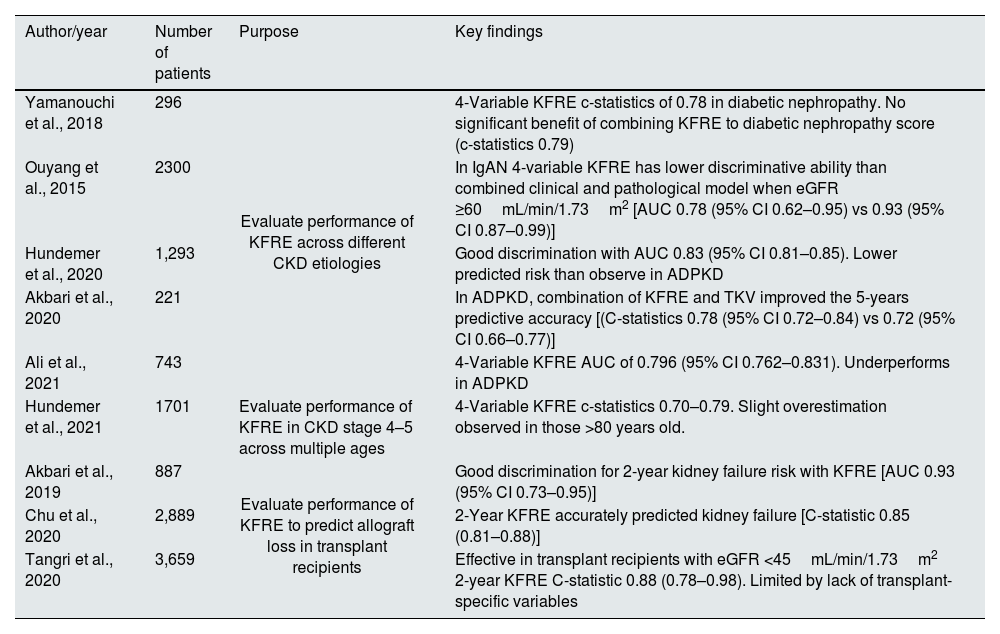

Multiple studies have demonstrated that the KFRE performed well in most disease aetiologies of CKD, including diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive nephropathy, glomerulonephritis, and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), as shown in Table 2.10,11,14

Summary of studies of KFRE use in particular clinical situations.

| Author/year | Number of patients | Purpose | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yamanouchi et al., 2018 | 296 | Evaluate performance of KFRE across different CKD etiologies | 4-Variable KFRE c-statistics of 0.78 in diabetic nephropathy. No significant benefit of combining KFRE to diabetic nephropathy score (c-statistics 0.79) |

| Ouyang et al., 2015 | 2300 | In IgAN 4-variable KFRE has lower discriminative ability than combined clinical and pathological model when eGFR ≥60mL/min/1.73m2 [AUC 0.78 (95% CI 0.62–0.95) vs 0.93 (95% CI 0.87–0.99)] | |

| Hundemer et al., 2020 | 1,293 | Good discrimination with AUC 0.83 (95% CI 0.81–0.85). Lower predicted risk than observe in ADPKD | |

| Akbari et al., 2020 | 221 | In ADPKD, combination of KFRE and TKV improved the 5-years predictive accuracy [(C-statistics 0.78 (95% CI 0.72–0.84) vs 0.72 (95% CI 0.66–0.77)] | |

| Ali et al., 2021 | 743 | 4-Variable KFRE AUC of 0.796 (95% CI 0.762–0.831). Underperforms in ADPKD | |

| Hundemer et al., 2021 | 1701 | Evaluate performance of KFRE in CKD stage 4–5 across multiple ages | 4-Variable KFRE c-statistics 0.70–0.79. Slight overestimation observed in those >80 years old. |

| Akbari et al., 2019 | 887 | Evaluate performance of KFRE to predict allograft loss in transplant recipients | Good discrimination for 2-year kidney failure risk with KFRE [AUC 0.93 (95% CI 0.73–0.95)] |

| Chu et al., 2020 | 2,889 | 2-Year KFRE accurately predicted kidney failure [C-statistic 0.85 (0.81–0.88)] | |

| Tangri et al., 2020 | 3,659 | Effective in transplant recipients with eGFR <45mL/min/1.73m2 2-year KFRE C-statistic 0.88 (0.78–0.98). Limited by lack of transplant-specific variables |

ADPKD: autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; IgAN: IgA nephropathy; TKV: total kidney volume.

Hundemer et al., demonstrated good discrimination across multiple aetiologies [2-year AUC 0.83 (95% CI 0.81–0.85)] in a cohort of 1293 advanced CKD patients. However, in ADPKD, the observed risk of kidney failure was higher than the predicted risk (42% vs 36%, p-value=0.07).11 In another study of 743 CKD patients with different disease aetiologies, KFRE showed good discrimination across the whole cohort [2-year AUC of 0.796 (95% CI 0.76–0.83)], but it also underestimated the risk in patients with ADPKD (63% vs 21%). This discrepancy may be attributed to the unique pathophysiology of ADPKD, which is more closely associated with cyst growth and total kidney volume than the variables included in the KFRE.10

A separate study explored the utility of incorporating total kidney volume (TKV) from ultrasound measurements to the KFRE for ADPKD patients to predict an eGFR decline of >30% or need for renal replacement therapy. The findings indicated that the combination of KFRE and TKV improved the 5-years predictive accuracy [(C-statistics 0.78 (95% CI 0.72–0.84) vs 0.72 (95% CI 0.66–0.77)]. Patients at higher risk demonstrating greater probabilities of adverse outcomes, such as lower baseline eGFR, larger TKV, and a higher prevalence of comorbidities.28

In a cohort of patients with diabetic nephropathy, Yamanouchi et al. found no significant benefit of combining diabetic nephropathy score of kidney biopsies and KFRE compared to KFRE alone for improving predictions of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) (c-statistics 0.79 vs 0.78, p=0.83).29

In a comparative study of risk prediction tools in immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN), in a cohort of 2300 Chinese patients, the KFRE had a similar discriminative ability compared to models incorporating clinical and pathological variables when eGFR <60mL/min/1.73m2 [AUC 0.90 (95% CI 0.79–0.88) vs 0.85 (95% CI 0.81–0.89)]. However in low-risk patients (eGFR ≥60mL/min/1.73m2), KFRE performed significantly worse than the model including kidney biopsy parameters [AUC 0.78 (95% CI 0.62–0.95) vs 0.93 (95% CI 0.87–0.99)].30

The KDIGO 2024 guidelines recommend using disease-specific and externally validated prediction equations in patients with ADPKD and IgAN, over more general CKD models such as KFRE.7

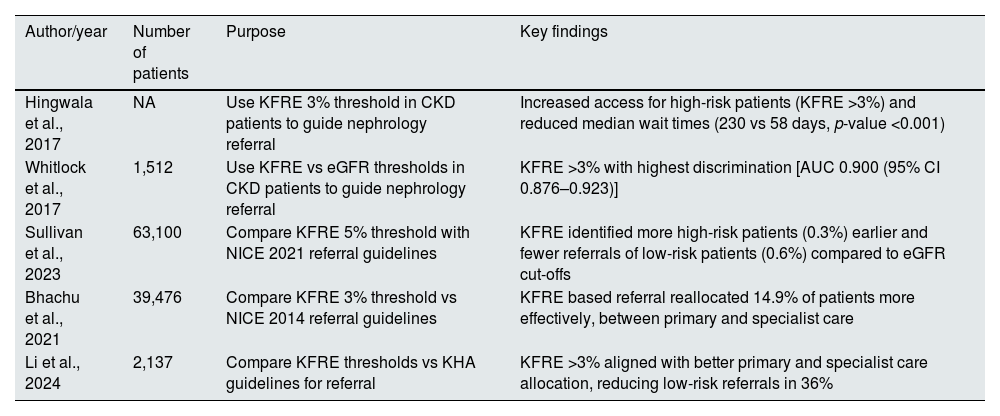

KFRE for nephrology referralIt was uncertain whether the KFRE could be effectively applied to CKD population to guide referrals to nephrology care. To address this, a validation study of the KFRE was conducted in a non-referred population in Manitoba, Canada. This study validated and compared KFRE risk thresholds of 3% and 10% with eGFR criteria (<45 and <30mL/min/1.73m2) and physician decisions for nephrology referral. The 3% threshold demonstrated higher discrimination [AUC 0.900 (95% CI 0.876–0.923)] than both eGFR thresholds [AUC 0.784 (95% CI 0.742–0.826)] and physician judgment [AUC 0.712 (95% CI 0.677–0.747)].31 These findings suggest that KFRE is highly effective in identifying patients at risk of progressing to kidney failure within five years, outperforming traditional eGFR measures and referral practices. Additionally, a retrospective evaluation was conducted on patients who started dialysis, focusing on their laboratory measurements of eGFR and ACR during the five years leading up to kidney failure. The results indicated that more than 94% of these patients had a predicted risk that exceeded the 3% risk threshold calculated by KFRE. The authors concluded that KFRE could be integrated into surveillance systems to identify patients with a high risk of progression. Particularly, a risk-based cutoff of 3% (sensitivity 97% and specificity 62%) could serve as a criterion for referrals to nephrology.

The KFRE was also evaluated as a part of a triage process for new nephrology referrals for patients with CKD stages 3–5.8 The four-variable KFRE was calculated for each referral and, if there were no other reasons that justified the referral, patients with KFRE <3% were classified as low-risk and returned to primary care. In contrast, patients with a KFRE >3% were classified as high-risk and scheduled for nephrology follow-up. This triage process was implemented in 2012. A comparison between the post-triage period (2013) and the pre-triage period (2011) showed an increase in the number of referrals. However, 34% of referrals in the post-triage period were not booked and were returned to primary care. Furthermore, median wait times improved significantly, from an average of 230 days in the pre-triage period to 58 days in the post-triage period (p-value <0.001). This demonstrates that applying the KFRE in a triage process can improve wait times, allowing patients at a higher risk for kidney failure to access specialized nephrology care more promptly.

Another study aimed to compare the guidelines of referral criteria with the KFRE thresholds. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2014 CKD guidelines and a KFRE threshold of more than 3% risk of ESRD at five years were applied to patients with CKD stages 3–5. The use of KFRE instead of NICE guidelines proved to reallocate almost 15% of CKD patients between primary and specialist care, favouring high-risk patients. The study also highlighted that about 40% of high-risk patients identified by the KFRE would not be referred using NICE 2014 CKD guidelines and 31.5% of low-risk patients would be unnecessarily referred. It translates into an increase of 11.1% in patients eligible for referral using KFRE, as a result of more high-risk patients being referred.32

A retrospective study in Australia examined whether the KFRE could more effectively guide the timing and appropriateness of CKD referrals compared to the Kidney Health Australia (KHA) guidelines. The results are consistent with those found in other studies, suggesting that a KFRE risk threshold of over 3% over a five-year period could reduce the number of specialist referrals by 36%, particularly in low-risk patients.

Furthermore, 76% of patients meeting KFRE criteria remained in follow-up, with only 8% being discharged, suggesting that these patients were more likely to maintain follow-up.33

These studies demonstrated that a KFRE threshold of greater than 3% over five years can be useful for referral to specialised nephrology care (Table 3). Therefore a risk-based approach can be better at identify high-risk patients who require specialized care and reduce unnecessary referrals of low-risk patients.

Summary of studies of KFRE use in guiding nephrology referral.

| Author/year | Number of patients | Purpose | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hingwala et al., 2017 | NA | Use KFRE 3% threshold in CKD patients to guide nephrology referral | Increased access for high-risk patients (KFRE >3%) and reduced median wait times (230 vs 58 days, p-value <0.001) |

| Whitlock et al., 2017 | 1,512 | Use KFRE vs eGFR thresholds in CKD patients to guide nephrology referral | KFRE >3% with highest discrimination [AUC 0.900 (95% CI 0.876–0.923)] |

| Sullivan et al., 2023 | 63,100 | Compare KFRE 5% threshold with NICE 2021 referral guidelines | KFRE identified more high-risk patients (0.3%) earlier and fewer referrals of low-risk patients (0.6%) compared to eGFR cut-offs |

| Bhachu et al., 2021 | 39,476 | Compare KFRE 3% threshold vs NICE 2014 referral guidelines | KFRE based referral reallocated 14.9% of patients more effectively, between primary and specialist care |

| Li et al., 2024 | 2,137 | Compare KFRE thresholds vs KHA guidelines for referral | KFRE >3% aligned with better primary and specialist care allocation, reducing low-risk referrals in 36% |

KHA: Kidney Health Australia; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

The NICE 2021 guidelines recommend using the four-variable KFRE for referring patients to nephrology, considering a threshold greater than 5% over five years.34 In a retrospective study of 160,000 patients with CKD, the KFRE was able to detect high-risk patients who did not meet other referral criteria (0.3% patients), and to recognize fewer low-risk referrals (0.6% patients) compared to using an eGFR threshold of less than 30mL/min/1.73m2.35

In accordance with these findings, the KDIGO 2024 CKD guidelines suggest that a five-year KFRE between 3% and 5% can be useful in determining the need for nephrology referral. As the KFRE is not validated for eGFR >60mL/min/1.73m2 it should not be used as a referral criterion to nephrology in these patients.7

Further research comparing KFRE thresholds of 3% and 5% could help determine which is the most appropriate threshold for referral. However, the implementation of KFRE is limited by the absence of routine urinary ACR testing.31,35,36 Therefore, enhancing ACR testing is vital for the broader application of KFRE and to allow for risk prediction tools to be automatically incorporated in reporting systems, particularly in primary care.37 While the KFRE can be a valuable tool for nephrology referrals, it should not be the sole criterion. Other indications for referral, such as rapid decline in eGFR, electrolyte abnormalities, refractory hypertension, haematuria and structural kidney diseases, must also be accounted for as indications for nephrology assessment.

Perception of patients and professionals about a risk-based approachA study performed in 2018 by Smekal et al. explored the perceived benefits and challenges of using a risk-based approach to CKD care using the KFRE. The results indicated that the KFRE could improve efficiency and resource allocation by targeting high-risk patients. Nonetheless, concerns were raised about the adequacy of care for lower-risk patients and primary care capacity.38 These findings highlight the importance of balancing efficiency with equitable access to care in CKD management.

Similarly, a subsequent study evaluated the implementation of the KFRE to guide access to multidisciplinary care for CKD patients and demonstrated that the KFRE-based approach successfully directed care toward those at the highest risk, with significant differences in patient care satisfaction related to access to care (p=0.01), caring staff (p=0.02) and safety of care (p=0.03). However, while most providers acknowledged the benefits of targeted care, some still expressed concerns about potential gaps in follow-up for low-risk patients.39

In line with these findings, a retrospective study examined the long-term outcomes of patients discharged from specialised CKD clinics, focusing on mortality and RRT initiation.40 Over a seven-year follow-up period, only 2% of discharged patients required RRT, and 8% were referred to nephrology again, suggesting appropriate discharge decisions. Furthermore, discharged low risk patients had a lower mortality rate compared to those who remained under specialised care [adjusted HR=0.45 [95% CI 0.25–0.78, p=.005)].40 These findings support the feasibility and safety of discharging low-risk CKD patients from nephrology care, reinforcing the effectiveness of risk-based stratification in optimizing healthcare resource allocation.

Another study explored the relationship between the KFRE and CKD care measures, including renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors use, blood pressure control, immunizations for influenza, pneumonia, and hepatitis B, as well as advanced CKD planning. The results highlighted that a higher KFRE is associated higher probability of completing advance directives (OR, 1.52; 95% CI 1.07–2.17) but lower probability of having BP under 140/90mmHg (OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.44–0.88).36 This underscores the need for improved risk-stratified interventions based on the KFRE to enhance CKD management and reduce CKD progression.

Vascular access planning and KFREThe KFRE development study mentioned potential uses for this tool, namely, the timing of appropriate pre-dialysis intervention.5 Different risk thresholds were suggested to guide clinical decisions concerning RRT, such as dialysis modality education, VA creation, and preemptive transplantation.

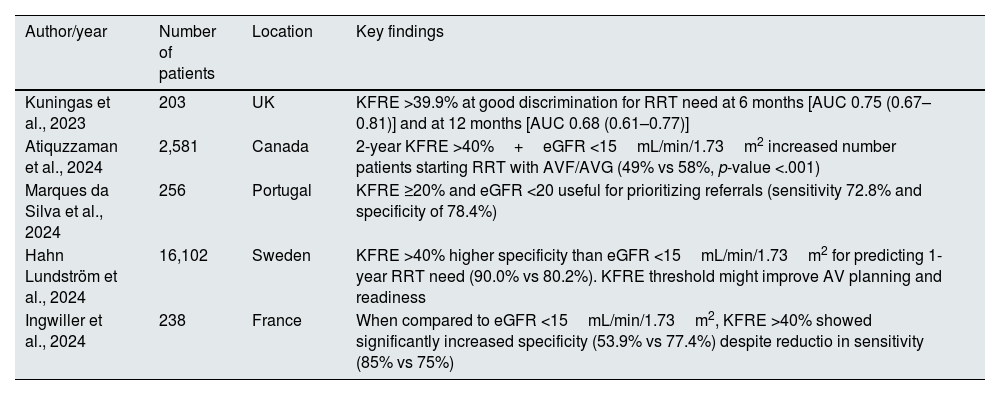

VA planning is particularly important since the most appropriate time to create a functional VA to initiate HD is still controversial. The summary of relevant studies is described in Table 4.

Summary of studies of KFRE in vascular access planning.

| Author/year | Number of patients | Location | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kuningas et al., 2023 | 203 | UK | KFRE >39.9% at good discrimination for RRT need at 6 months [AUC 0.75 (0.67–0.81)] and at 12 months [AUC 0.68 (0.61–0.77)] |

| Atiquzzaman et al., 2024 | 2,581 | Canada | 2-year KFRE >40%+eGFR <15mL/min/1.73m2 increased number patients starting RRT with AVF/AVG (49% vs 58%, p-value <.001) |

| Marques da Silva et al., 2024 | 256 | Portugal | KFRE ≥20% and eGFR <20 useful for prioritizing referrals (sensitivity 72.8% and specificity of 78.4%) |

| Hahn Lundström et al., 2024 | 16,102 | Sweden | KFRE >40% higher specificity than eGFR <15mL/min/1.73m2 for predicting 1-year RRT need (90.0% vs 80.2%). KFRE threshold might improve AV planning and readiness |

| Ingwiller et al., 2024 | 238 | France | When compared to eGFR <15mL/min/1.73m2, KFRE >40% showed significantly increased specificity (53.9% vs 77.4%) despite reductio in sensitivity (85% vs 75%) |

UK: United Kingdom.

In a retrospective analysis of 190 pre-dialysis patients, the use of eGFR resulted in a substantial number of unnecessary fistula creation, since 23.7% of the patients did not use the VA. However, the patients who did not start dialysis had a significantly lower KFRE (37.5%) than those who did start dialysis (57.4%), suggesting that KFRE could have avoided unnecessary arteriovenous fistula (AVF) creation. The optimal cut-off value was a KFRE >39.9% at 6 months [AUC 0.75 (0.67–0.81)] and 12 months [AUC 0.68 (0.61–0.77)].41

A Portuguese cohort demonstrated that a KFRE score ≥20% is considered an optimal threshold for prioritizing VA referrals [HR for starting RRT within 2 years: 9.2 (5.06–16.60); sensitivity 72.8% and specificity of 78.4%].42 The thresholds identified by this study might differ from other due to local practices and timings for VA surgery.

In a Swedish study of 16,102 patients, a KFRE >40% demonstrated higher specificity than eGFR <15mL/min/1.73m2 for predicting RRT within a year, 90% (89.7–90.3) and 80.2% (79.8–80.5), respectively, suggesting that using KFRE thresholds could increase the proportion of patients initiating HD with a functional AVF or arteriovenous graft (AVG). Additionally, the mean time from referral with a KFRE >40% and RRT initiation was about a year, allowing adequate time for VA maturation. In patients with an increased risk of unnecessary surgery, such as older individuals and patients with comorbidities, using the combination of KFRE >40% and eGFR <15mL/min/1.73m2 is considered preferable.43 This ensures both precision and broader detection, guaranteeing appropriate care while reducing unnecessary surgical interventions.

Similarly, Atiquzzaman et al. demonstrated that the number of patients initiating HD with AVF/AVG increased (49% vs 58%, p-value <.001) when an adjunct 2-year KFRE of >40% was used in addition to eGFR threshold. Moreover, unnecessary VA creation also decreased with combined use of 2-year KFRE and eGFR compared to eGFR alone (31% vs 18%, p-value <0.001). This study also highlighted the importance of correct KFRE thresholds establishment, since an adjunct 2-year KFRE of ≤40% would not have recommended 366 patients for AVF/AVG creation who started HD within 2 years, misclassifying patients as not being referred for VA creation.44

A retrospective French study compared the predictive abilities of the KFRE >40% to an eGFR <15mL/min/1.73m2 and demonstrated that the KFRE has higher specificity (77.4% vs 53.9%,), which translates into a reduced premature AVF creation. However, the KFRE showed a slight reduction in sensitivity compared to eGFR (75% vs 85%).45

Regarding the timing for RRT preparation, KDIGO now suggests using the 2-year KFRE threshold greater than 40%, in addition to eGFR-based criteria and other clinical considerations.7 The use of the KFRE enhances decision making when compared to eGFR alone, as it allows for reducing unnecessary interventions and having more functional AVF/AVG at haemodialysis start. Further research is required to refine KFRE thresholds and referral timing for VA planning, ensuring better adaptation to local clinical practices in VA creation.

Utility of the KFRE in kidney transplant recipientsThe KFRE has been extensively validated in CKD patients stages 3–5, to predict the progression to kidney failure and the need to initiate RRT. However, kidney transplant recipients might also have progressive graft disfunction leading to kidney failure. Studies assessing the discriminative ability of KFRE in kidney transplant patients are presented in Table 2.

In 14-year retrospective study of 887 kidney transplant recipients, Akbari et al. demonstrated that the 4-variable KFRE had reliable accuracy in predicting kidney failure [2-year KFRE AUC 0.93 (95% CI 0.73–0.95)].46

More recent studies exposed that the KFRE accurately predicted allograft failure in those who had their graft for more than 2 years [2-year C-statistic 0.85 (0.81–0.88)] and in patients with an eGFR of less than 45mL/min/1.73m2 [2-year C-statistic 0.88 (0.78–0.98)].47,48 Therefore, the KFRE can be useful for nephrologists since it accurately predicts kidney transplant failure. Nevertheless, the KFRE was not developed to evaluate this population and does not account for important variables used to evaluate kidney transplant patients, such as donor characteristics, histopathology, or immunological parameters. Moreover, the KFRE does not predict all-cause mortality or acute rejection episodes.48

Further research is required to recommend the routine use of the KFRE in this specific population.

Risk prediction and healthcare costsStudies have also examined the influence of the KFRE in predicting healthcare costs associated with CKD. In CKD stage 3 patients, a 1% increase in the 8-variable KFRE corresponded to a 13.5% increase in monthly healthcare costs. A similar increase in the KFRE was linked to a 4.1% rise in costs for CKD stage 4 patients.49

High-risk patients utilize more healthcare resources, with more hospital admissions and physician visits, and hospitalization being the primary cost driver. These findings suggest that identifying high-risk patients is advantageous, as it facilitates the implementation of better care strategies, which can ultimately reduce long-term costs.50

Future directionsAs the use of the KFRE becomes increasingly embedded in nephrology care pathways, several future directions merit attention to enhance its clinical impact. Firstly, broader integration into electronic health record (EHR) systems will be essential for consistent application across diverse healthcare settings, namely with automated calculation and decision support prompts.51 Real-time alerts based on KFRE thresholds could support timely referral, VA planning, or enrolment in multidisciplinary clinics without relying solely on clinician memory or initiative.

Secondly, there is still a lack of evidence on the impact of incorporating the KFRE into shared decision-making tools for patients, particularly those approaching kidney failure, may enhance patient engagement and alignment of care with individual goals and preferences.52 Interactive risk communication platforms which present KFRE results in accessible formats are under development and may facilitate discussions around dialysis initiation, listing for transplantation, conservative management, and advanced care planning.

There is also growing interest in using KFRE to stratify populations for clinical trial enrolment and health system interventions. For example, enrichment strategies based on KFRE thresholds could improve trial efficiency by targeting individuals at highest risk for progression. Similarly, KFRE-based triage models may help prioritize high-risk patients for nephrology access in resource-limited settings.

Finally, as newer biomarkers and machine learning models emerge, the role of the KFRE within evolving risk prediction frameworks will need reassessment. Hybrid approaches combining KFRE with additional clinical and biomarker data may further refine prediction accuracy, although the simplicity and accessibility of the original equation remain major strengths.

ConclusionThe KFRE has evolved from a prognostic research tool into a practical instrument for risk-based and patient-centered care in CKD. Its validated accuracy, simplicity, and adaptability have enabled integration into diverse clinical workflows – from nephrology referral to vascular access planning and conservative care discussions. However, its application must be accompanied by critical awareness of key limitations, such as the competing risk of death, reduced performance in very elderly populations, and the need for local recalibration. Additionally, barriers to implementation persist, particularly in health systems where urinary ACR is not systematically measured. Addressing these challenges transparently will enhance its utility for clinicians. Moving forward, the KFRE offers a strong foundation for personalized CKD care.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNone declared.