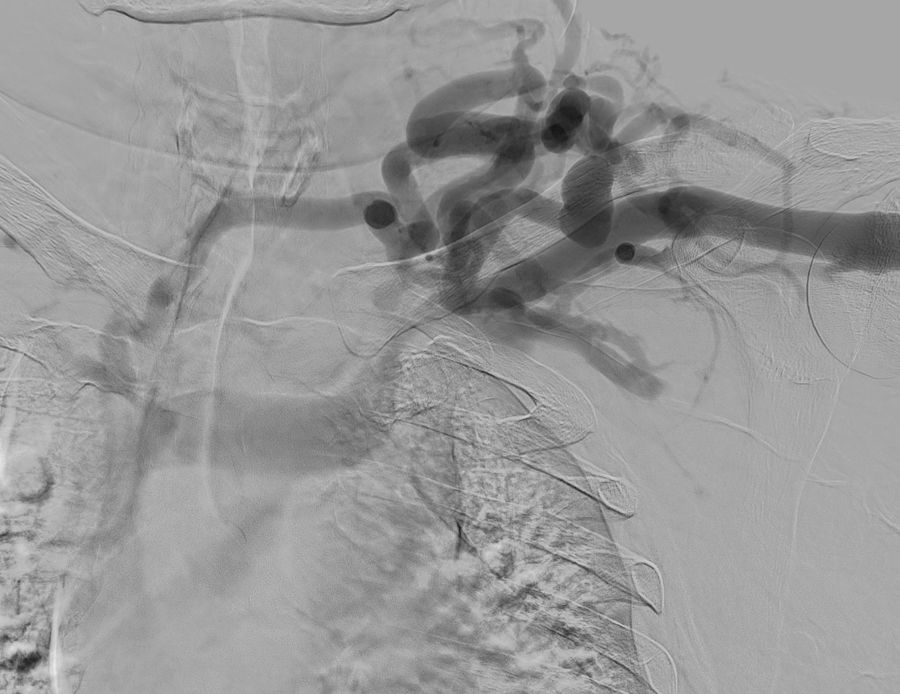

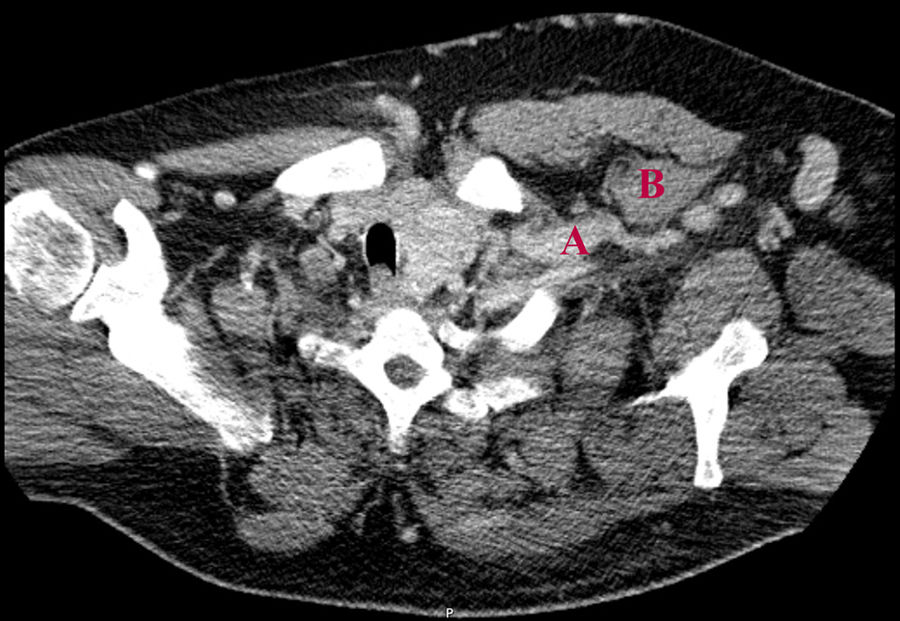

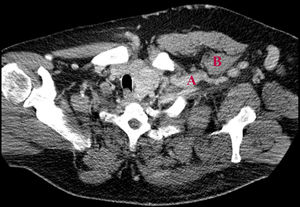

We present the case of a 50-year-old man with a history of chronic kidney disease due to probable glomerulosclerosis secondary to obesity, for years the patients have been on regular haemodialysis through a left humeral-cephalic arteriovenous fistula. He presented with chronic oedema and stasis changes in the left upper arm caused by increased venous pressure in relation with obstruction of the subclavian vein due to thoracic outlet syndrome confirmed by fistulogram (Fig. 1) and CT angiography (Fig. 2).

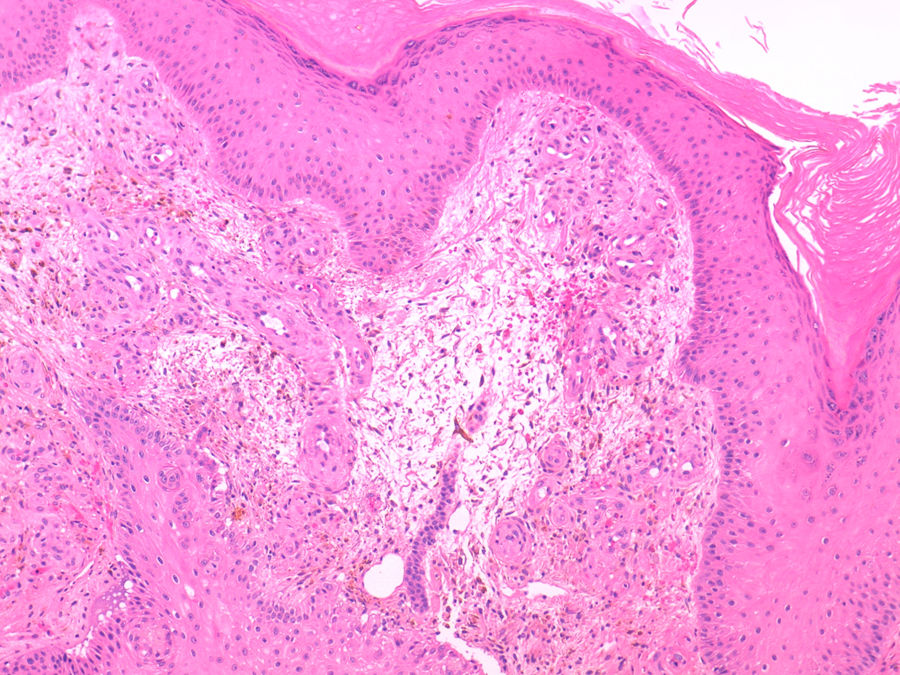

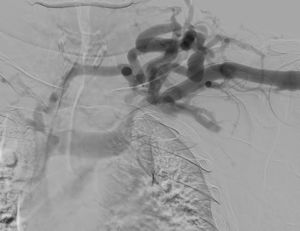

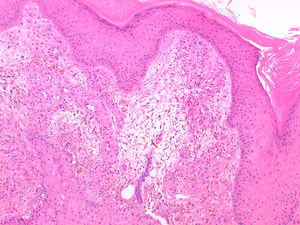

He was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of a plaque with progressive growth on the back of the left hand, with a verrucous appearance, brownish-purple in colour, with central ulceration and well-defined borders (Fig. 3). The histological study showed, in the superficial dermis, multiple thick-walled capillaries lined by endothelial cells without evidence of atypia, as well as extravasation of red blood cells and the presence of haemosiderophages (Fig. 4). The culture of the skin lesion was negative.

The diagnosis of Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome was confirmed. It was decided conservative treatment with serial cures, with the lesion resolving after months of follow-up.

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome is classified, together with acroangiodermatitis of Mali, within the group of clinical conditions known as pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.1

It is a rare disease described mainly in relation to underlying arteriovenous malformations. However, the literature includes cases secondary to iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulas used for treatment with haemodialysis.2 Although its pathogenesis is still unknown, it is considered that the increase in venous pressure and the distal ischaemia produced by the arteriovenous steal syndrome would cause the proliferation of endothelial cells.3

Its clinical presentation is variable, with single or multiple, purplish-brown lesions with progressive growth and the possibility of secondary ulceration. When the disease develops in dialysis patients, the lesions usually appear on an oedematous limb with other ischaemic-stasis skin changes, such as hyperpigmentation or hypertrichosis.1,2

Although the diagnosis is eminently clinical, a histopathological and microbiological study makes it possible to rule out neoplastic processes, such as sarcoma or squamous cell carcinoma, as well as chronic skin infections, such as those caused by atypical mycobacteria.2

In most cases, treatment is conservative, based on compression and elevation of the limb which favours venous return. In addition, it is essential the care of ulcers and the treatment of possible superinfections. Definitive treatment would imply closure of the arteriovenous fistula.1

Although it is a rare condition, Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome is a potential complication of arteriovenous fistulas that must be recognised in dialysis patients.

Please cite this article as: Silvestre-Torner N, Aguilar-Martínez A, Tabbara-Carrascosa S, Herrero-Berrón JC, Suso A, Gálvez-González E. Síndrome de Stewart-Bluefarb asociado a una fístula arteriovenosa iatrogénica. Nefrologia. 2022;42:112–114.