Smoking is a known preventable risk factor for vascular diseases. However, it is one of the most forgotten risks when we talk about its relationship with kidney disease. Following the publication of the “Consensus statement on smoking and vascular risk” promoted by the autonomous societies of hypertension and vascular risk of Spain, we consider that the nephrology community should be alerted about the deleterious effects of exposure to tobacco smoke and its consequences on renal damage. Something to take into account given the prevalence of smoking in our environment, approaching its prevention and treatment.

El consumo de tabaco es un conocido factor de riesgo evitable para las enfermedades vasculares, sin embargo, parece uno de los grandes olvidados cuando hablamos de su relación con la enfermedad renal. A raíz de la publicación del “Documento de consenso sobre tabaquismo y riesgo vascular” promovido por las sociedades autonómicas de hipertensión y riesgo vascular de España, consideramos que se debe alertar a la comunidad nefrológica sobre los deletéreos efectos por los que la exposición al humo del tabaco daña el riñón. Algo a tener muy en cuenta, por la prevalencia del tabaquismo en nuestro medio, además de su tratamiento y prevención.

The causal relationship between smoking and the development of cardiovascular disease is widely recognized. Tobacco use is the main cause of avoidable premature vascular morbidity and mortality and continues to be the most relevant risk factor for the prevention of these diseases and others, as important as cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In addition, passive exposure to tobacco smoke also increases vascular risk (VR). In contrast, cessation of tobacco use in any of its forms1 (including related products such as e-cigarettes) and avoidance of environmental exposure to tobacco smoke have major health benefits after cessation. However the relationship between smoking and kidney disease is not well known.

Tobacco consumptionIn Spain, despite the progressive social awareness and legislation developed in recent years, smoking continues to be a very prevalent risk factor. Of particular concern is the maintenance of the age of initiation (14 years) and the high consumption among women and young people of either sex.

The Spanish Heart Foundation Health Survey (ESFEC) of 2021 reports a smoking prevalence among the Spanish population of 15.9%.2 The Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in Spain 1995–2022 (EDADES) shows that 33.1% of Spanish residents aged 15–64 years have consumed tobacco daily during the last 30 days, the highest figure in the whole of Spain being that of Extremadura (43%). By sex, the figures for daily consumption during the last month are higher in men (42.2%) than in women (32.0%),3 however, women smoke more than men between the ages of 15 and 25.

It is estimated that nine out of every 10 adult smokers acquire this unhealthy and addictive habit before they finish high school. This means that if children and adolescents avoid smoking, they will probably never become smokers. Thus it is evident the importance of smoking prevention in childhood and adolescence. In this respect, the State Survey on Drug Use in Secondary Education 2023 (ESTUDES) shows that, after alcohol, tobacco is the second psychoactive substance with the highest prevalence of consumption among students aged 14–18 years.4 A total of 33.4% of students admit that they have smoked tobacco at some time in their lives, with this proportion dropping to 27.7% for use in the last 12 months, and to 21.0% for use in the last 30 days. There has been has been a downward trend since 2006, and a drop in the prevalence of tobacco use is again observed in the three time periods analyzed, thus recording the lowest consumption data for this substance in the entire historical series. With respect to daily tobacco consumption in the last 30 days, it is observed that, in 2023, the prevalence stands at 7.5%, which represents a drop of 1.5 percentage points with respect to the 2021 figure, also registering the lowest value for this indicator in the entire historical series. With respect to the average age of initiation of consumption, a stabilization has been observed in recent years. Both the average age of onset of consumption has been stable at 14.1 years since 2016 and the average age of onset of daily consumption has barely undergone any variation since 2012, standing at 14.6 years.

Tobacco and kidney diseaseChronic kidney disease (CKD) affects 10% of the world's population and is among the top 10 noncommunicable diseases contributing to disease and disability. Its incidence is increasing worldwide and mortality increased from 0.9 million to 1.2 million deaths annually between 2005 and 2017. CKD also imposes a significant economic burden on patients and society; many developed countries spend 2%–3% of their annual healthcare expenditure on renal replacement therapy.

The relationship between smoking and CKD raised questions about causality in the past, as risk factors such as lower sociodemographic status, obesity, hypertension, and sedentary lifestyle, traditionally associated with smoking, were considered to coexist. However, it is now accepted that smoking is an independent risk factor for kidney damage, since it has been found that smokers are more likely to develop kidney failure compared to non-smokers.5,6 In fact, several recent meta-analyses involving millions of participants have confirmed this observation.7,8

In adition, it has been shown that the risk of developing CKD decreases with time after quitting smoking and increases with cumulative exposure to tobacco, suggesting a dose-dependent effect in the cause-effect relationship.9

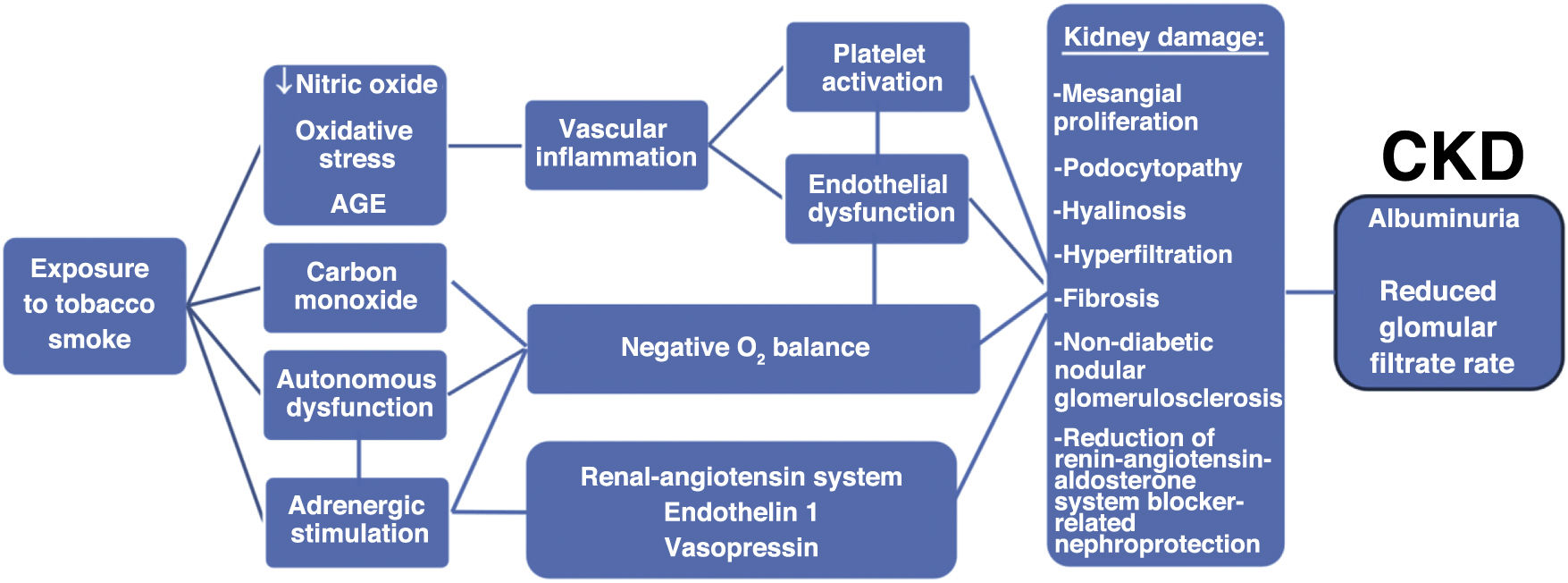

The mechanisms linking smoking to renal damage (Fig. 1) are not yet fully elucidated, but processes such as increased oxidative stress and advanced glycation products (AGEs), activation of angiotensin-II and endothelin-1, altered lipoprotein metabolism, increased vascular permeability, endothelial dysfunction, and induction of pathological vascular changes in the kidney or insulin resistance have been proposed.10–13 Altered patterns of DNA methylation have also been observed in smokers that may explain the unfavorable renal function results in ex-smokers, since these epigenetic alterations take many years to recover.14 Alterations in podocyte ultrastructure, mesangial proliferation and the appearance of idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis have been invoked as smoking-associated renal parenchymal lesions.15,16

Tobacco and albuminuriaAlbuminuria (UEA) is a common feature of CKD. This phenomenon reflects not only damage to the glomerular filtration barrier, but is also the result of altered glomerular hemodynamics and hyperfiltration, as well as the inability of renal tubular cells to completely recover filtered albumin.17 In both diabetics and non-diabetics, microalbuminuria is a predictor of the progression of nephropathy and a powerful independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.18,19 Likewise, the correlation observed between microalbuminuria and mortality in studies with high-risk patients is noteworthy. For example, in the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study, microalbuminuria predicted mortality in patients with high VR (9.4% without albuminuria versus 18.2% with albuminuria).20 Such an association between albuminuria and mortality has been demonstrated even in the general population. In the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End Stage Disease (PREVEND) study, Hillege et al. showed that a 2-fold increase in urinary albumin excretion was associated with a 29% increased risk of cardiovascular death and a 12% increased risk of non-cardiovascular death.21

The data available in the literature indicate a clear relationship between tobacco consumption and albuminuria. Thus, in the HOPE study itself, the effect of smoking on albuminuria was reviewed, finding a clear correlation between the two. More recently, in a large study with 152,896 participants with hyperglycemia, Kar et al. observed that, compared to nonsmokers, smokers were at greater risk of suffering albuminuria (odds ratio [OR] = 1.26 [1.10–1.44]).22 Also in diabetic patients, a meta-analysis with 105,031 participants demonstrated the adverse impact of smoking on the development not only of macroalbuminuria (OR = 1.65 [1.03–2.66]), but also of microalbuminuria (OR = 1.24 [1.05–1.46]).23 Similarly, this latter association of smoking with moderately increased albuminuria has been repeatedly confirmed by different groups also in the general population, even with hyperfiltration and often identifying a dose-dependent effect.24–28 It does appear that the effect of smoking on albuminuria is more evident with increasing age, but the association remains significant even after adjusting for demographics and other risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia.25 Furthermore, smoking is capable of reversing the favorable nephroprotective effect conferred by treatment with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers.29

ConclusionsGiven the importance of smoking reduction in the prevention and treatment of renal and vascular risk, our group recommends that colleagues read the consensus document on smoking and vascular risk.30

We would also like to add some of his considerations that we believe are appropriate for the nephrological community. Smoking continues to affect a significant sector of the Spanish population and is a factor that increases cardiovascular risk, since it is a pathogenic agent for the increase in arteriosclerosis, which is the common basic substrate of cardiovascular disease and is closely linked to the development and progression of CKD. All smokers should be assessed for their degree of dependence, their motivation to quit and the probability of success of the therapies. Anti-smoking advice is very cost-effective and should always be given, but the approach to smoking cessation in the smoking patient requires the involvement of the nephrologist and the collaboration of a multidisciplinary team made up of doctors, nurses and psychologists, among others. We have effective pharmacological treatments to help smoking cessation, most of them financed by the public health system. For those who are not able to quit smoking, a strategy based on tobacco harm management with a total switch to smoke-free products could be a less dangerous alternative for their health than continuing to smoke.

FinancingThis editorial has not received specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector or non-profit entities.