To assess the prevalence of kidney failure in patients from a primary care centre in a basic healthcare district with laboratory availability allowing serum creatinine measurements.

DesignAn observational descriptive cross-sectional study.

Data sourcesA basic healthcare district serving 23,807 people aged≥18 years.

ResultsPrevalence of kidney failure among 17,240 patients having at least one laboratory measurement available was 8.5% (mean age 77.6±12.05 years). In 33.2% of such patients an occult kidney failure was found (98.8% were women).

Prevalence of chronic kidney failure among 10,011 patients having at least 2 laboratory measurements available (≥3 months apart) was 5.5% with mean age being 80.1±10.0 years (most severely affected patients were those aged 75–84); 59.7% were men and 76.3% of cases were in stage 3. An occult kidney failure was found in 5.3% of patients with women being 86.2% of them (a glomerular filtration rate<60mL/min was estimated for plasma creatinine levels of 0.9mg/dl or higher).

ConclusionsComparison of present findings to those previously reported demonstrates the need for further studies on the prevalence of overall (chronic and acute) kidney failure in Spain in order to estimate the real scope of the disease. Primary care physicians play a critical role in disease detection, therapy, control and recording (in medical records). MDRD equation is useful and practical to estimate glomerular filtration rate.

Evaluar la prevalencia de la insuficiencia renal en los pacientes de un centro médico de un área básica de salud que disponen de determinaciones analíticas de creatinina sérica.

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo observacional transversal.

Fuentes de datosÁrea básica de salud con 23.807 usuarios de ≥18 años de edad.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de la insuficiencia renal entre los 17.240 pacientes que disponían de, al menos, una analítica fue del 8,5%, con una media de edad de 77,6±12,05 años. Un 33,2% de los afectados presentaba una insuficiencia renal oculta, siendo un 98,8% mujeres.

La prevalencia de la insuficiencia renal crónica entre los 10.011 pacientes que disponían de al menos 2 analíticas separadas por ≥ de 3 meses fue del 5,5%, siendo su media de edad de 80,1±10,0 años (el grupo más afectado fue el de 75 a 84 años), un 59,7% hombres, y un 76,3% de los casos con estadio 3. Un 5,3% de los afectados presentaban una insuficiencia renal oculta, el 86,2% de estos eran mujeres (se calculaba un filtrado glomerular < 60mL/min ya con niveles de creatinina plasmática de 0,9mg/dl).

ConclusionesLa comparación de los resultados actuales con los previos reportados pone de manifiesto la necesidad de realizar nuevos estudios de prevalencia de la insuficiencia renal global, crónica y oculta en España para poder valorar el alcance real de la enfermedad. El médico de atención primaria juega un papel fundamental en la detección, tratamiento, control y registro de la enfermedad (en la historia clínica). La fórmula MDRD resulta útil y práctica para estimar el filtrado glomerular.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an important, growing worldwide healthcare problem due to population ageing and to the increase in its risk factors. Its high cardiovascular (CV) and total morbidity and mortality, high healthcare costs and important social implications make early diagnosis and treatment necessary. To do so, it is necessary for medical professionals at all levels of the healthcare system to be aware of this problem. Multidisciplinary clinical guidelines should also be established for the management of these patients and their subsequent referral to nephrologists.

According to the K/DOQI guidelines, CKD is classified into stages of severity based on glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and the existence of kidney lesions of ≥3 months1,2; more recently, the detection of significant albuminuria has been added as a criteria.2 In daily clinical practice other terms are still frequently used, like “renal failure” (RF) (GFR<60mL/min/1.73m2: corresponds with stages 3–5) and “chronic renal failure” (CKD) (RF for ≥3 months). “Occult renal disease” (ORD) refers to the situation in which RF occurs with normal serum creatinine levels.

In Spain, numerous studies of prevalence of RF (GFR equivalent to stages 3–5) done in different populations lead to non-uniform results. Those done in the general population ≥18 years treated in primary care clinics (PC) reported rates of 7% (43.5% were ORD),3 14.5%,4 16.4% (26.1% ORD)5 and even 21.3% in the EROCAP study (the largest done in our country on CKD in PC, with 7202 patients with 37.3% ORD)6; in patients older than 64 and 70, prevalences of ORD were 21.2 and 33.7% respectively.6,7

Multiple studies and meta-analyses have confirmed that reduced GFR is an important risk for CV and total morbidity/mortality. CV risk factors and established CV disease lead to CKD and this, in turn, leads to CV disease, which is the first cause of death.8–14 This is why patients with CRF are at high or very high CV risk, and many authors consider CRF equivalent to heart disease and, therefore, eligible for therapeutic measures and objectives for secondary CV prevention.14–16 CRF screening is currently recommended, especially in high-risk populations15; the best screening method uses GFR estimation based on different formulas (especially the MDRD equation and, more recently, the CKD-EPI2).

ObjectivesThe main objective of the study was to evaluate CRF and ORD prevalence in patients from Primary care (PC) medical clinics based on the same healthcare district (BHD). Patients evaluated had serum creatinine data recorded in their medical files. The prevalence of RF was likewise determined.

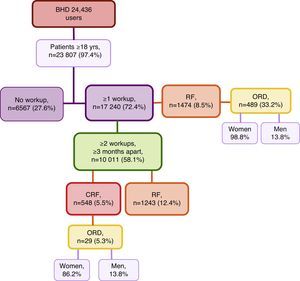

Material and methodsStudy designOurs is a cross-sectional, observational, descriptive study with a retrospective component carried out in a BHD with 24,436 potential users, 23,807 of which were ≥18 years of age. Included in the study were 17,240 of these patients who had at least one blood test with creatinine levels. The study period was from October 2001 to April 2014.

VariablesThe data collected included demographic variables, information from the computerised PC patient files and laboratory parameters. The serum creatinine determination method used was Jaffé kinetic method. The abbreviated MDRD-4 formula was used to estimate GFR.

For this study, we considered that the patient had RF if the GFR was <60mL/min/1.73m2, CRF if the RF persisted on 2 analyses separated by ≥3 months, and ORD if the RF or CRF had normal serum creatinine levels (estimated as <1.2mg/dL in women and <1.3mg/dL in men).

As the study was cross-sectional but had a retrospective component, the index Cr was the last available at the time of the study, obtained at the clinic and the previous Cr was from the preceding test by more that 3 months.

Statistical analysisUsing SPSS version 16.0 software, a descriptive study was created to express the results of the quantitative variables as means and standard deviation (X¯±SD); the qualitative variables were expressed as percentages.

ResultsFirst, we studied 17,240 (72.4%) of all patients of the BHD who were ≥18 years of age who had been treated at the medical centre and had at least one recorded analytical determination of serum creatinine level. Mean age was 57.8±19.1, versus a mean age of 39.5±14.6 for those patients who did not have lab results available in their files. Among these patients, 1474 (8.5%) presented RF with a mean age of 77.6±12.05 (range 20–102years). Out of all these cases of RF, 489 (33.2%) represented ORD, with 483 (98.8%) cases in women and 6 (1.2%) in men (Fig. 1). When we reviewed the list of pathologies recorded in the computerised files of the 1474 patients with RF, 34.1% had the diagnostic code for CRF.

Second, we selected the group of patients of the BHD≥18 years of age who had at least 2 serum creatinine values obtained separated by ≥3 months so the prevalence of RF and CRF was determined. This condition was met by 10,011 patients with a mean time elapsed between the 2 blood tests of 13.8±10.3 months (range 3–98.4months). Initially, we only contemplated the last available Creatinine. We found that 1243 (12.4%) presented RF (Fig. 1); by stages: 88.7% were stage 3, 9% were stage 4 and 2.2% stage 5. Review of medical charts revealed that 36.8% had the diagnostic code for CRF (this code was also present in 6.3% of the patients with GFR>60mL/min/1.73cm2).

Then, we analysed the latest blood tests as well as the previous test available that was ≥3 months prior. It was found that 548 (5.5%) patients presented CRF, with a mean age of 80.1±10.0 (range 24–99 years). By sex, 327 (59.7%) of the affected patients were men; by age groups, the greatest prevalence (40.3%) was between 75 and 84 years (Table 1); by stages, 76.3% of the cases were stage 3 CRF (Table 2). Of all the CRF, 29 (5.3%) were ORD, 25 (86.2%) of which were in women; mean age was 85.4±6.7 and 4 (13.8%) cases were men (Fig. 1). The creatinine level for a GFR<60mL/min was 0.9mg/dL in women and 1.2mg/dL in men. Upon review of the computerised medical charts of the patients with CRF, we observed that 67.7% had the diagnostic code for CRF.

CRF by age groups and sex.

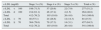

| Age groups (yrs) | CRF n (%) | No CRF n (%) | Total | CRF prevalence (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||

| <65 | 29 (80.6) | 7 (19.4) | 2103 (43.3) | 2758 (56.7) | 4897 | 0.7 |

| 65–74 | 82 (78.8) | 22 (21.2) | 992 (45.5) | 1189 (54.5) | 2285 | 4.5 |

| 75–84 | 128 (57.9) | 93 (42.1) | 685 (40.8) | 993 (59.2) | 1899 | 11.6 |

| ≥85 | 88 (47.1) | 99 (52.9) | 253 (34.1) | 490 (65.9) | 930 | 20.1 |

| Total (sexes) | 327 (59.7) | 221 (40.3) | 4.033 (42.6) | 5430 (57.4) | 10,011 | |

| TOTAL | 548 (5.5) | 9463 (94.5) | 10,011 | |||

CRF, chronic renal failure.

CRF by stages and sex.

| CRF stage | Men n (%) Age (yrs) (X¯±DE) | Women n (%) Age (yrs) (X¯±DE) | Total n (%) Age (yrs) (X¯±DE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 261 (79.8) | 157 (71.1) | 418 (76.3) |

| 78.2±10.1 | 83.4±7.3 | 80.2±9.5 | |

| 3a | 166 (50.8) | 48 (21.8) | 214 (39.0) |

| 77.5±10.3 | 81.9±8.2 | 78.5±10.0 | |

| 3b | 95 (29.0) | 109 (49.3) | 204 (37.3) |

| 79.4±9.5 | 84.0±6.8 | 81.9±8.5 | |

| 4 | 48 (14.7) | 56 (25.3) | 104 (18.9) |

| 79.3±8.6 | 83.0±11.0 | 81.3±20.1 | |

| 5 | 18 (5.5) | 8 (3.6) | 26 (4.8) |

| 74.2±12.1 | 71.9±21.4 | 73.5±15.1 | |

| Total | 327 (59.7) | 221 (40.3) | 548 (100.0) |

| 78.2±10.0 | 82.8±9.3 | 80.1±10.0 | |

CRF, chronic renal failure.

The analytical parameters registered in the patients with CRF are shown in Table 3. The LDL cholesterol (c-LDL) levels were determined depending on the stage of renal involvement: 51.2% of patients presented levels <100mg/dL and 15.5% <70mg/dL (Table 4).

Analytical parameters registered by stages.

| Variables | Stage 3 | Stage 3a | Stage 3b | Stage 4 | Stage 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5±0.2 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.6±0.2 | 2.5±0.5 | 5.6±1.8 | 1.9±1.1 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 176.7±35.3 | 177.4±34.6 | 176.0±36.2 | 168.4±38.7 | 154.2±37.7 | 174±36.5 |

| c-HDL (mg/dL) | 47.1±12.5 | 46.7±12.8 | 47.6±12.1 | 45.2±13.7 | 45.9±17.6 | 46.7±13.0 |

| c-LDL (mg/dL) | 104.7±32.1 | 105.4±31.2 | 104.0±33.2 | 97.8±35.9 | 73.6±28.3 | 101.9±33.3 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 106.0±34.1 | 107.4±37.4 | 104.5±30.3 | 108.8±32.1 | 104.3±23.7 | 106.4±33.3 |

| HBA1C (%) | 6.1±1.2 | 6.0±1.3 | 6.2±1.1 | 6.3±1.4 | 5.4±0.9 | 6.1±1.3 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.0±1.9 | 13.6±1.9 | 12.4±1.8 | 13.1±11.8 | 11.0±1.1 | 12.9±5.4 |

Levels of LDL cholesterol according to CRF stage.

| c-LDL (mg/dl) | Stage 3 n (%) | Stage 4 n (%) | Stage 5 n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-LDL<100 | 198 (71.5) | 57 (20.6) | 22 (7.9) | 277 (51.2) |

| c-LDL≥100 | 214 (81.1) | 46 (17.4) | 4 (1.5) | 264 (48.8) |

| Total | 412 (76.2) | 103 (19.0) | 26 (4.8) | 541 (100.0) |

| c-LDL<70 | 48 (57.1) | 24 (28.6) | 12 (14.3) | 84 (15.5) |

| c-LDL≥70 | 364 (79.6) | 79 (17.3) | 14 (3.1) | 457 (84.5) |

| Total | 412 (76.2) | 103 (19.0) | 26 (4.8) | 541 (100.0) |

The prevalence of RF detected in the population of adult patients who were treated at a BHD medical centre and had at least one lab test with creatinine was 8.5%, and 33.2% of which were ORD. Nonetheless, we found that the prevalence of CRF was 5.5%, although this percentage increased to 10% in patients over the age of 64 and to 20.1% in those over the age of 85; only 5.3% of cases had ORD.

When data reported by other authors about the epidemiology of renal disease in Spain was reviewed and compared with our series, we observed that the main limitation of all previous CRF prevalence studies was that they are cross-sectional and based on the estimation of GFR from a single blood test. Thus, it is not possible to differentiate between patients with transitory kidney involvement (acute intercurrent disease, nephrotoxic drugs, etc.) and those with established CRF.

Considering this limitation, we compared the different rates of renal involvement observed after evaluating one or more serum creatinine values. We determined the prevalence of the disease in 2 groups of patient: those with only one blood test available and those with 2 or more. In the first group, the study began by determining the prevalence of RF (global: acute and chronic), which was 8.5% and, therefore, lower than most studies done in PC that range between 73–5 and 21.3% of the EROCAP study.6 The reasons for these differences could be explained by different methodologies used to evaluate blood tests, patient clinical stability, different range for normal creatinine levels (non standardised determination), the occasional use of other formulas to estimate GFR and, perhaps, largest number of included patients.

Based on the timeframe that defines CRF that was systematically obviated in the past, the study was continued in the second group of patients (those with ≥2 blood tests that were ≥3 months apart). We found that when RF prevalence was determined according to the latest blood test, the resulting percentage was 12.4%. However, as could be expected, when 2 analyses were assessed, the prevalence of CRF dropped to 5.5%; this was presumably due to the exclusion of transitory reductions in GFR. Nonetheless, it is surprising to observe that in patients with CRF the percentage of stages 4 and 5 was twice as high as in RF while the percent of patients in stage was slightly decreased (Table 5). This observation is contrary to what was expected because GFR estimation using the MDRD formula requires a stable creatinine concentration and, therefore, presents limitations especially for GFR levels around 60mL/min/1.73cm2, which are most susceptible to change in certain patients (those with special diets, significantly altered muscle mass, extreme body mass indices, severe liver disease, etc.) and in situations of acute concomitant morbidity. Additionally, this finding, once again, demonstrates the importance of correctly evaluating the data on epidemiology of CKD. The estimation of prevalence based on a single lab test may result in underestimation of the prevalence of more advanced disease stages.

Prevalence of RF (based on one serum creatinine determination) and CRF (based on 2 determinations) and their stages in the 10,011 patients with 2 blood tests that were ≥3 months apart.

| Creatinine determinations | GFR<60mL/min/1.73cm2 | Stages according to GFR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 Blood test, n (%) | 1243 (12.4) | 1103 (88.7) | 112 (9) | 28 (2.2) |

| 2 Blood tests, n (%) | 548 (5.5) | 418 (76.3) | 104 (18.9) | 26 (4.8) |

GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Thus, the prevalence of CRF found in our series (which is 5.5%) is the lowest reported (keeping in mind the limitations when comparisons are made with previous studies). However, it probably better reflects the actual situation of CKD in the population of our series. Therefore, the remainder of the study was centred around this group of patients.

We observed a close relationship between CRF and age, which is a well-known relationship, although mean patient age in our patients (80.1±10.0years) was older than in other reports. When analysed by age, prevalence of CRF in patients over the age of 64 was 10% (vs. 21.2 and 33.7%, previously reported in patients over the age of 64 and 70, respectively6,7), but this increased to 20.1% in patients ≥85 years (Table 1). With regards to sex, as reported by some authors, RF slightly affected more men than women,5,6 although these women patients were older.

As far as severity of CRF, most cases were mild-moderate (stage 3, especially 3a), a fact that has also been observed in other studies.5 This finding emphasises the opportunity of PC physicians to diagnose CKD at early stages and, consequently, to initiate appropriate therapies to slow the progression of the disease and reduce CV and other complications, which is especially effective if initiated in stages 2 and 3.15

The association of CKD, especially stages 3–5, with CV involvement has been repeatedly demonstrated in several populations. The greater CV morbidity and mortality of these patients is due to the presence of a higher prevalence of classic CV risk factors and other factors inherent to nephropathy (altered mineral metabolism and arterial calcification, endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, inflammation, malnutrition, anaemia, etc.) in addition to the deleterious effects of treatment and therapeutic limitations typical of these patients (less use of ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, antithrombotics, percutaneous coronary interventions, etc.).9

Although the management and treatment of this disease have greatly advanced in recent years, compliance with current recommendations is far from optimal in numerous healthcare settings. The fact is that, to reduce CV events and slow renal function loss, it is necessary to implement integral management plans with preventive CV measures, including lifestyle changes, diet and pharmacological treatment. According to European recommendations for CV prevention, patients with moderate CRF (GFR 30–59mL/min/1.73m2) are considered at high CV risk, and patients with severe CRF (GFR<30mL/min/1.73m2) are very high risk. These conditions are comparable to established ischaemic heart disease; therefore, it is recommended to establish objectives for secondary CV disease prevention. Likewise, the CKD consensus document developed by Spanish scientific societies in 2012 states that CKD is equivalent to other coronary disorders and, therefore, treatment objectives are the same as in patients with ischaemic heart disease.14,15,17–19 More recently, a document of the Spanish Society of Nephrology states that patients with CKD in stages 3–5 are at high CV risk.20 Given these assessments and with regards to dyslipidaemia treatment in these patients, it is reasonable to achieve c-LDL levels <100mg/dL in CRF stage 3 and <70mg/dL in CRF stages 4 and 5 (without dialysis) by prescribing statins.14

Regarding our BHD series, to evaluate CV morbidity and what is adequate or not for the therapeutic management of patients with CRF, it would have been necessary to compile patient medical histories, complementary tests e (ECG, echocardiogram, other blood analyses, etc.) and treatments that had been prescribed. However, such data collection was not obtained because the patient data registration and codification in the computerised PC medical files is physician-dependent; furthermore given the study characteristics, the variables were not systematically recorded for assessment and analysis. Both of these circumstances would result in greater data variability and less reliability. For this reason, we only collected automatically recorded laboratory parameters (from the laboratory database), demographic data and, if available, the pathologic history of CRF (albuminuria, which, although it is an important parameter for assessing CKD, was not contemplated because many patients did not have this information available). In fact, it was observed that only 67.7% of patients with confirmed CRF had the CRF diagnostic code among their list of diseases, this code is observed in only one-third of patients with RF (acute or chronic) and even in some patients with maintained GFR. This demonstrates not only the insufficient use of the CRF code (whether diagnosed or not) but also the poor use of the term because the time criterion that defines it is often not considered.

As for the control of CV risk factors, only half of the patients with CRF presented c-LDL levels <100mg/dL and only 15.5% had <70mg/dL. Furthermore, patients with severe CRF presented most favourable lipid levels (Table 3). This could reflect how more intense therapies are applied in advanced disease stages and in patients who, theoretically, are receiving nephrological treatment. These results illustrate the need to increase the awareness of PC physicians about the importance of diagnosing the disease first of all, treating it second of all, and then properly recording it in patient files so that CV risk can be estimated along with the potential risk for presenting other complications and adverse pharmacological effects. Progress has been made in this direction in recent years and, as the PC setting is essential for the detection and control of CKD, clear criteria have been established for the management and referral of these patients to specialists in nephrology.20

Last of all, the prevalence of ORD was evaluated. This is a frequent situation in daily practice because renal function is generally estimated according to plasma creatinine levels alone (which is favoured by the fact that the laboratory does not automatically offer GFR estimation results using the formulas available). As we have commented previously, these levels varied due to several factors (age, sex, weight or muscle mass, diet, etc.) so that the mathematical relationship between these 2 variables is an hyperbola.21 Studies done in different healthcare settings report ORD prevalences that ranged from 26 to 49.3% of all RF cases (given that said studies have the same limitations that RF prevalence studies demonstrate). It was also observed to affect almost exclusively seniors and women3–7,22 who were generally in stage 3. In the series, and coinciding with these findings, ORD represents one-third of all RF cases. In CRF patients, however, it is interesting that just 5.3% presented ORD, although in both circumstances it still almost exclusively affects women and patients of older age.

The fact that in women GFR<60mL/min was detected with creatinine levels of 0.9mg/dL leads us to believe that the current threshold for normal (1.2mg/dL) is not very sensitive for RF screening. Thus, these results suggest: (a) GFR should be estimated using formulas, when possible, which are especially valid in women and in seniors (a population that is usually polymedicated and in treatment with drugs that are susceptible to dose adjustments or contraindicated in RF)7; and, (b) given the frequency with which renal function is assessed by serum creatinine, the threshold for normal should be lowered to avoid errors and situations of ORD, especially in women (for the creatinine determination method of this study, values of <0.9mg/dL should be considered normal).

LimitationsPossible study limitations include: (a) this is a prevalence study in patients treated at our BHD health center who had at least one blood test, which may have led to selection bias and an overestimation of the actual prevalence of kidney disease; (b) systematic lab tests at 3-month intervals were not available for this study, and mean time transpired between tests was a little more than one year; (c) the MDRD formula used to estimate GFR has a series of limitations itself, including being based on serum creatinine levels, whose determination is not standardised.

ConclusionsConsidering the results of this present study and previous reports by other authors, it seems obvious that, in order to assess the actual scope of renal disease in Spain, new prevalence studies are necessary for RF, CRF and ORD. The comparison and analysis of the prevalences found in this series demonstrate significant variability depending on the number of creatinine determinations studied and, likewise, the important limitations of the studies published to date.

Furthermore, in the battle against CKD, it is fairly clear that PC physicians play an essential role in the detection (which in most cases could be a mild-moderate stage of CRF), control and treatment of these patients. Proper patient management also involves correctly recording this pathologic history in patient medical files because these data are of prognostic and therapeutic importance. The MDRD formula is a good tool for determining GFR; in addition to estimating CRF severity, it is also able to estimate the CV risk of these patients.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gentille Lorente D, Gentille Lorente J, Salvadó Usach T. Repetición de la medición de creatinina sérica en atención primaria: no todos tienen insuficiencia renal crónica. Nefrologia. 2015;35:395–402.