To the Editor,

IgA nephropathy is the most frequent primary glomerulopathy in the world.1,2 It is often presented as macroscopic haematuria (generally preceded by a respiratory infection in the upper airways, especially in children), and persistent microhaematuria with mild proteinuria. Nephrotic syndrome and acute renal failure are the least common manifestations. We describe the case of an elderly patient that was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy, as a result of rapidly progressive renal failure (RPRF).

The patient was a 78-year-old man with a history of prostate carcinoma, treated with brachytherapy and radiotherapy check-ups every 6 months; carpal tunnel syndrome; right hip operation; and no known drug allergies.

His doctor had referred him to the emergency department due to tiredness and pain in his lower limbs. The patient’s medical records indicated that he had suffered from nocturia on two occasions. The physical examination performed upon admission indicated that the patient’s general condition was fair. He was conscious and aware of his surroundings. He did not have jugular ingurgitation. Blood pressure was 135/85mm Hg, heart rate was 82 beats/min and SatO2: 92%. The heart auscultation was rhythmic and pulmonary auscultation presented hypoventilation with isolated wheezing. The rest of the examination was normal.

The blood analysis (emergency department) was: creatinine: 2.9mg/dl (previous creatinine: 1.2mg/dl); potassium: 5.3mEq/l; haemoglobin: 11.5g/dl; haematocrit: 34.7%; remaining analyses, including venous gasometry and the coagulation test, were normal.

Systematic urine analysis showed: protein +++, blood ++. The sediment test showed haematuria, with isolated hyaline casts.

Chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound did not show any pathological findings, the kidneys were of normal size, and the excretory tract was not dilated.

The subsequent blood analysis (common) showed: creatinine: 3.9mg/dl; urea: 181mg/dl; albumin: 2.7g/dl; total protein: 5g/dl; calcium: 6.9mg/dl; phosphorus: 8.1mg/dl; uric acid: 8.3mg/dl; sodium: 132mEq/l. 24-hour urine test found microalbuminuria, which was 620µg/min (normal range: 0-15µg/min). Other supplementary tests performed were normal (including viral serology, blood culture, tumour markers and thyroid hormones). The immunological test only showed a decrease in IgG of 574mg/dl (normal value: 751-1560) and an increase in C-reactive protein to 8.7mg/dl. No monoclonal peak was detected on the electropherogram.

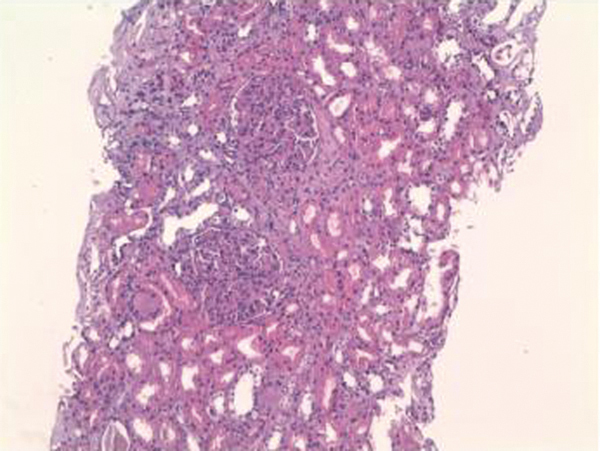

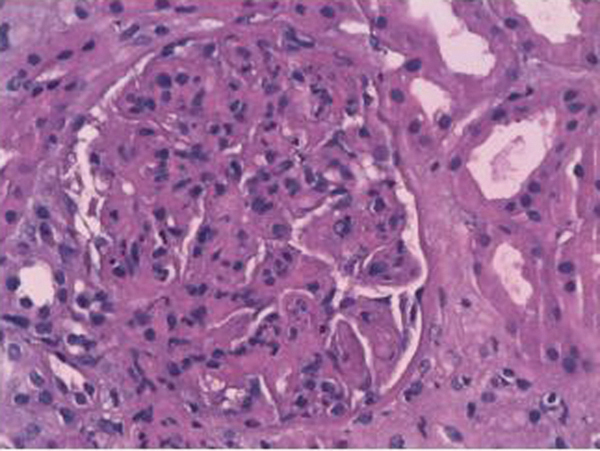

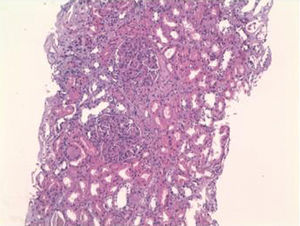

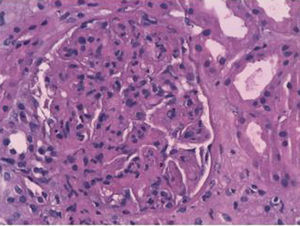

The patient had been admitted to the internal medicine department, where progressive deterioration of the renal failure and oligoanuria were confirmed. Renal replacement therapy with haemodialysis was started. Given the rapidly progressive acute renal failure, a kidney biopsy was performed, finding the following: 12 glomeruli per cross-section, none of which was sclerotic. We observed an expansion of the mesangial matrix with cellular proliferation in all of the glomeruli examined. On occasions, they affected the whole glomerulus, with pseudo-lobe images of the vascular tuft. There were fibrinoid necrosis foci in three glomeruli. The immunofluorescence showed intense positivity for IgA and C3, being negative for IgG and IgM. All the alterations found pointed to mild acute tubular necrosis with mixed inflammatory infiltration. The final diagnosis was IgA nephropathy with diffuse proliferation and fibrinoid necrosis foci (Figures 1 and 2).

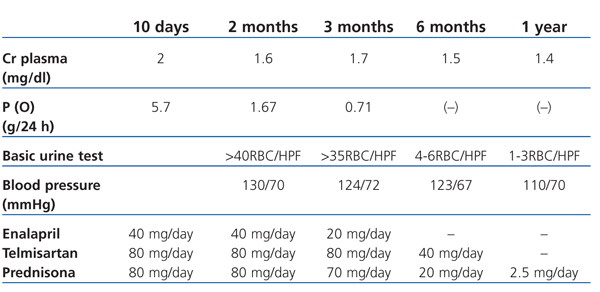

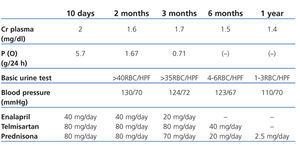

As well as the support therapy with furosemide, enalapril was administered at 40mg/day, irbesartan 150mg/day and doxazosin 8mg/day. The biopsy findings lead to administration of three pulses i.v. of 1g of 6-methylprednisolone followed by prednisone at a dose of 1mg/kg/day. Diuresis was recovered with these measures, and kidney function gradually improved without the need for dialysis (creatinine reduced from 5.4mg/dl to 2mg/dl upon hospital discharge). Table 1 shows the follow-up and progress following hospital discharge.

There are mild forms of IgA nephropathy that can go unnoticed. In fact, in some autopsy and biopsy studies conducted to assess renal grafts, IgA nephropathy can be found in around 1.5% of the normal population.3 We describe the case of an elderly patient, who had no previous nephrology problems, who was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy following a kidney biopsy to confirm the cause of RPRF.

IgA nephropathy can appear at any age, but most frequently during the second and third decades of the life.4 It is possible that the prevalence in the elderly population is higher than has been described in the literature, possibly due to kidney biopsy indication. Persistent urinary alterations may attribute to other concomitant disorders (prostatitis, infections, etc.) and if a kidney biopsy is not performed, IgA nephropathy may be underdiagnosed.5 Given our patient’s history of prostate carcinoma, this nephropathy could have gone unnoticed if it had not been for obvious manifestations of acute renal failure.

Although this nephropathy is the most frequent one, an optimum treatment has not been well-established.6 Based on a review of 20 years experience, a third of these patients can develop end-stage chronic kidney disease (ECKD).7 Two studies have recently been published which have shown the benefits of co-administering corticoids (short-term) and angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE) to treat IgA nephropathy with moderated histological lesions, with proteinuria above 1g/day.8,9 Combined immunosuppressant therapy is indicated in patients with rapidly progressive active severe disease and with histological evidence of active severe inflammation (crescents).10 In our case, we treated a patient with a history of rapidly progressive prostate cancer, with diffuse proliferation and fibrinoid necrosis foci and with no chronicity data. We decided to treat the patient with i.v. pulsed steroids followed by oral steroids with ACE and angiotensin II receptor antagonists. The patient progressed satisfactorily.

In summary, we have reported one more IgA case in an elderly patient, which probably would have gone unnoticed if the aggressive clinical symptoms had not started.

Figure 1. Haematoxylin and eosin (20x) with two glomeruli with intense diffuse proliferation of the capillaries.

Figure 2. Haematoxylin and eosin (40x) with one glomerulus with intense diffuse proliferation and fibrinoid necrosis foci.

Table 1. 12-month clinical follow-up following hospital discharge