To the Editor,

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) affects the physical condition of the patients and has an impact on mental health.1 Anxiety and depression are the two most commonly associated psychological disorders with chronic kidney diseases (CKD).2

Depression is an affective disorder that is associated with a sense of loss that many patients experience when faced with renal failure, since they lose autonomy, their physical health deteriorates, and watch as their family and occupational roles are altered. Despite being the most common psychological problem among patients with CKD, depression has not been adequately studied in relation to the different stages of the disease.3

Anxiety, the second most commonly associated pathology with CKD, is a warning response produced by the body to situations of danger, threat, or change. However, when anxiety is maintained in the absence of danger, or cannot be coped with, it becomes pathological. This leads to behavioural changes4 in the patient that alter relationships with health professionals and the family, and can even lead to non-compliance with medical treatment.

In addition, suffering from one of these two psychological disorders in the initial stages of CKD is a predictor for elevated mortality in patients that reach later stages.5 Although technological advancements have enabled us to reduce the mortality of patients with CKD, depression and anxiety increase the risk of suicide.6

The high prevalence of depression in patients with CKD is mediated by the combination of the physical symptoms of depression and the symptoms experienced by dialysis patients, which are the consequence of nephrological disease. Since this combination can lead to an over-estimation of the prevalence of this psychological problem in renal patients, we need to improve the precision and accuracy of the diagnostic process. One way to improve in this area is to use the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),4 as we did in our study, as this does not take into account physical symptoms in the overall score for diagnosing depression, but only cognitive symptoms that are characteristic of this mood disorder.7

With this in mind, we examined the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with ADPKD. We also sought to determine whether clinical variables could be correlated with the specific symptoms characteristic of these two psychological disorders.8

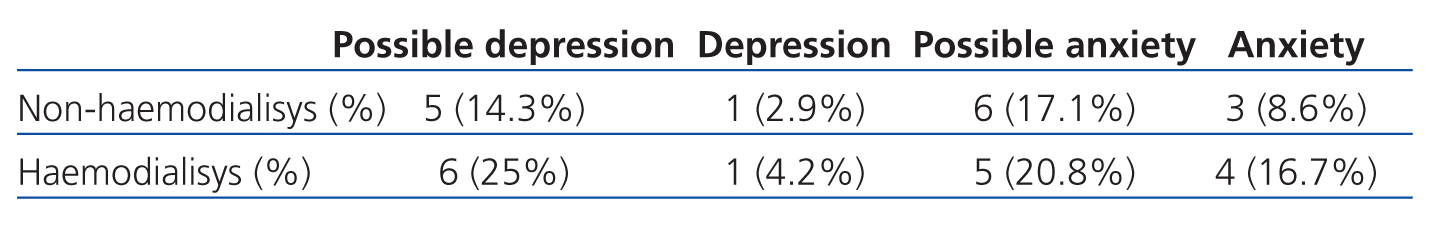

The first objective of our study was to calculate the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with ADPKD (Table 1). The prevalence of these to psychological disorders in patients with ADPKD on haemodialysis (HD) was lower than in those without ADPKD that were undergoing the same treatment (55.9% of patients with depression and 46.72% of patients with anxiety). However, the estimated rates of depression in non-HD patients were similar to those observed by Hedayati et al.9 We are unable to establish comparisons with the prevalence of anxiety in non-HD patients, since no studies have been carried out in this field.

Our second objective was to establish which specific symptoms of these two psychological disorders were associated with two clinical variables (time on HD and time since diagnosis). Our predictions were less exact in this subject, since no studies have specifically examined this topic.

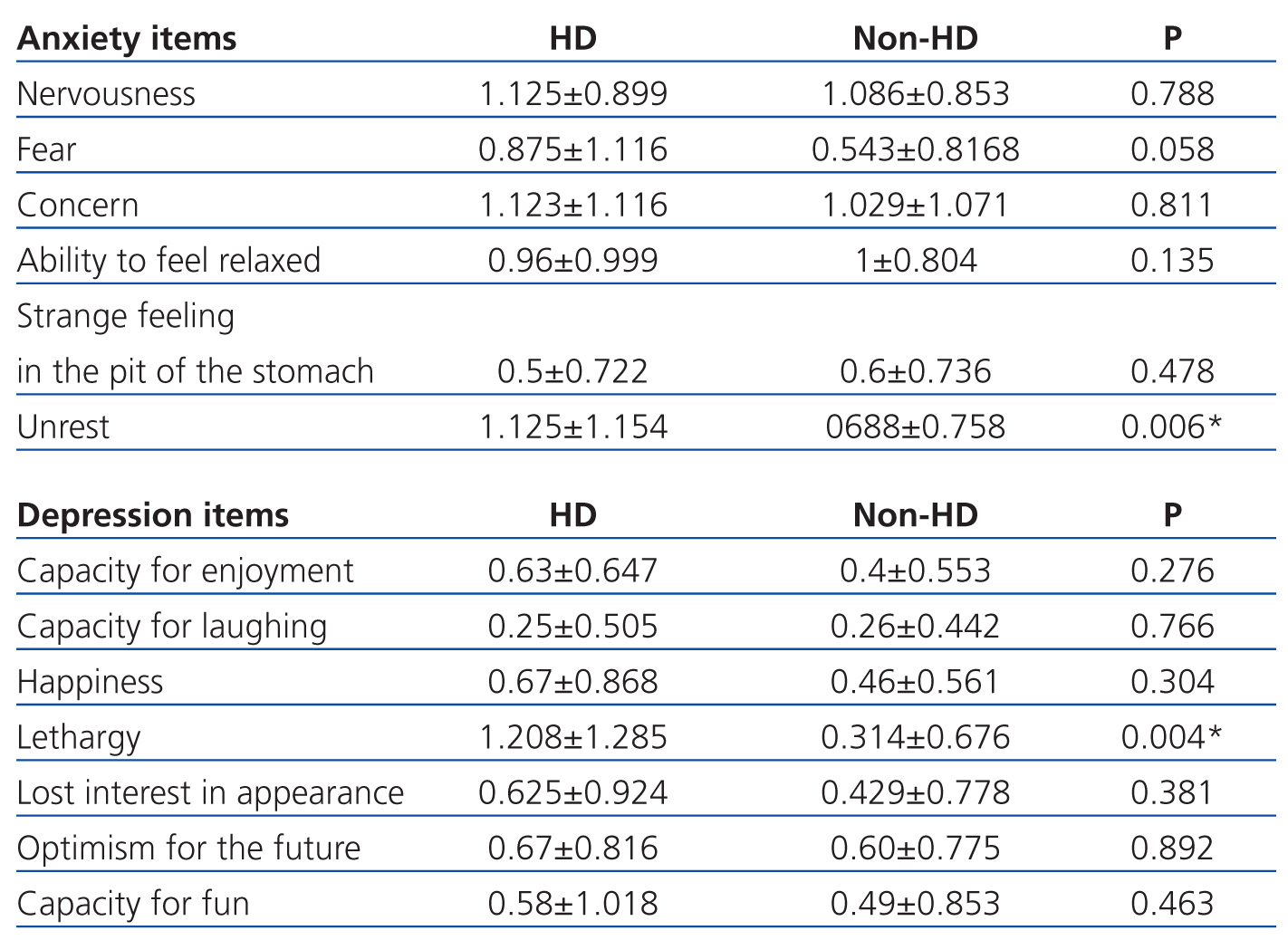

A detailed analysis of questionnaire items and clinical variables, which specifically examined the relationship between HADS and HD/non-HD, time on HD, and time since the diagnosis, revealed several significant differences.

We observed that HD/non-HD influenced the feeling of lethargy and unrest and it appears that the duration of dialysis treatment plays an important role in several items (Table 2). As Watnick et al10 showed, symptoms of depression and anxiety are most common at the start of dialysis.

We also observed that scores for a feeling of lethargy (Table 2) were higher in patients that had spent 2.2-22 years on HD, as compared to those with only 0-4 months of treatment. Contrary to the aforementioned results regarding anxiety, the latter finding is supported by several studies that affirm those patients that have been on dialysis for more than one year have a greater tendency for depression.11

Our results also suggest that the time since the patient was diagnosed with kidney disease is significantly correlated with feelings of concern and sudden panic (Table 2). In this manner, scores were higher among patients that had been diagnosed with ADPKD for 0-12 months than in those who had been diagnosed with ADPKD for 14-25 months. We believe that this finding confirms that concern regarding this disease is strongest immediately following diagnosis.

In conclusion, our study shows that patients with ADPKD have a higher prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression than in the general population,12 regardless of whether or not they are undergoing dialysis treatment. More studies are necessary that examine psychological aspects of patients with ADPKD in order to attend to their biopsychosocial needs in the best possible manner. An early identification of psychological problems along with a study of the context in which they have arisen allows us to reduce the disparity between long-term and short-term progression and development of kidney disease, as well as to improve patients’ quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This article was made possible by funding from the Canary Islands Savings Bank (Caja de Canarias) and the Mapfre Guanarteme Foundation for the genetic and psychosocial study of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the province of Las Palmas (Análisis Genético y Evaluación Psicosocial de pacientes con Poliquistosis Renal Autosómica Dominante en la Provincia de Las Palmas).

Conflicts of interest

The authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Table 1. Scores for the hospital anxiety and depression questionnaire

Table 2. Mean score for each item on the hospital anxiety and depression questionnaire