Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the most frequent manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and affects approximately 40% of patients. Renal involvement represents an important risk factor for morbidity and mortality, and 10% of patients with LN will develop advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) during their follow-up.1 During the last decades we have witnessed the duality of treatment in sequential therapy between intravenous cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate accompanied by glucocorticoids.2 However, the final result with this therapeutic strategy was a complete remission rate between 20 and 30%, a 20–35% relapse rate after three to five years, a high percentage of side effects of the drugs used, resulting in a high burden of accumulated damage that translated into high morbidity and a decrease in the patient’s quality of life.3 In recent years, the arrival of new drugs aimed at various specific therapeutic targets, together with the appearance of different American and European guidelines on the management of lupus and LN, have brought about a significant revolution, achieving a higher percentage of remissions, a reduction in the dose of glucocorticoids and improvement of the quality of life of these patients.4–7

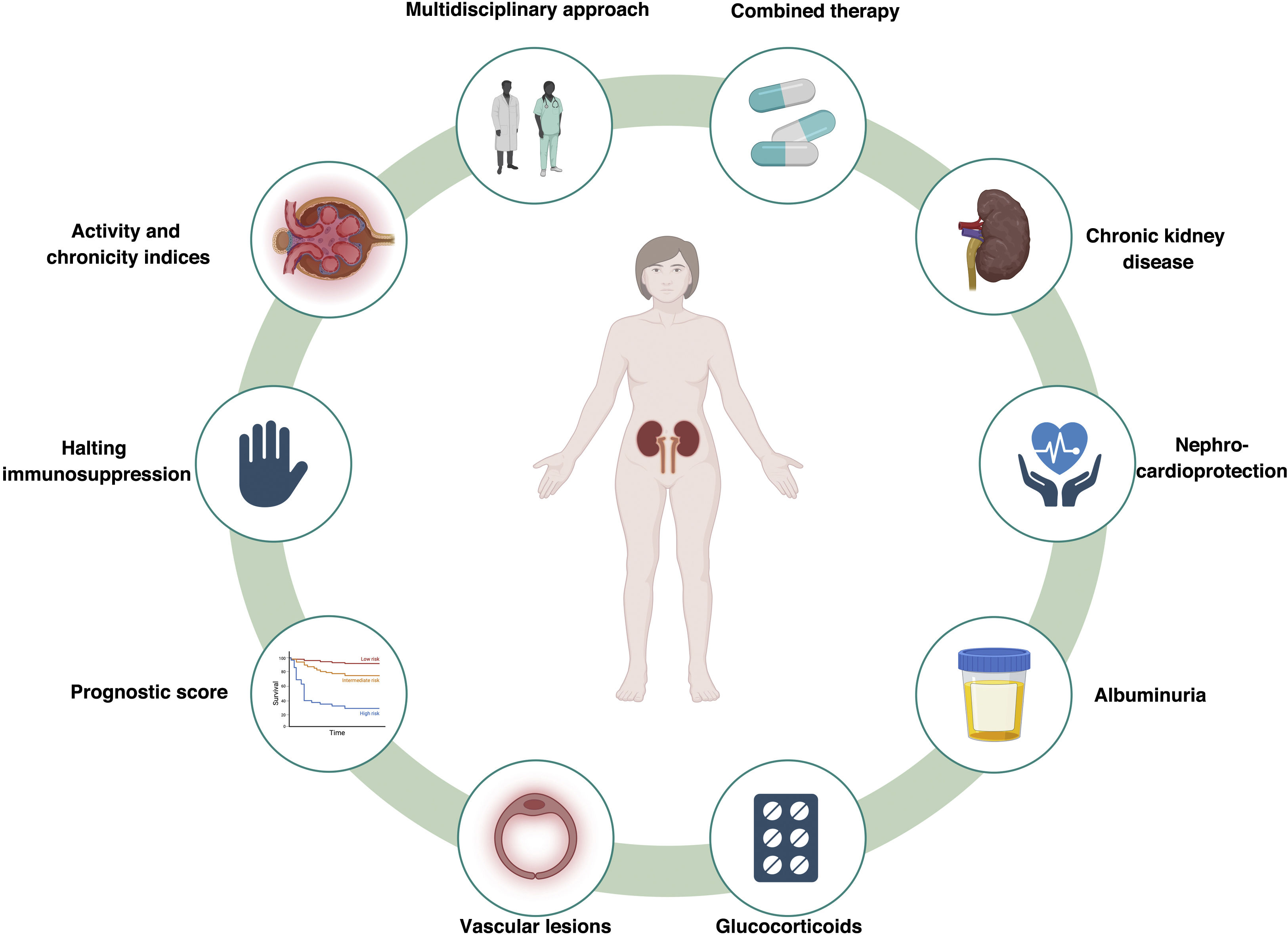

However, this new perspective on lupus and LN has generated new unresolved questions that deserve special attention (Fig. 1).

A multidisciplinary view of lupus: breaking down barriers between medical specialtiesIn recent years, a great step forward has been made in the integral vision of the lupus patient. This new situation has meant that different specialists consider the lupus patient as part of a care process with different manifestations and which requires a consistent diagnostic and therapeutic approach.8 This holistic view of the disease means that the approach to the lupus patient is clearly different, seeking specific objectives such as prevention of accumulated damage, avoiding relapses, questioning the different comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, infection prevention, screening for neoplasms, etc.), and managing the possible complications of pregnancy. To achieve all these objectives, we need to intensify strategies focused on a healthier lifestyle and select more personalized immunosuppressive treatments with fewer side effects within a strategy imported from the world of rheumatology known as “treat to target”.9

From sequential therapies to combination of therapiesWe continue to use a nomenclature imported from the world of oncology, and we talk of induction and maintenance treatment for autoimmune diseases. We have always been struck by the use of the same immunosuppressive drug (cyclophosphamide according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines or mycophenolate mofetil or mycophenolic acid derivatives) for the use of these sequential therapies (induction and maintenance). During the last few years, the different clinical trials in the LN world (BLISS-LN [Efficacy and Safety of Belimumab in Adult Patients with Active Lupus Nephritis], AURORA [Aurinia Renal Response in Active Lupus With Voclosporin] and NOBILITY [A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Obinutuzumab Compared With Placebo in Participants With LN]) have shown us that from the outset the combination of several drugs with different targets of action would allow us to speak of a “multitarget therapy” according to the clinical, immunological and histological characteristics of the patient with LN.10–12

Perhaps it would be more advisable to speak of combined therapies as an approach to our therapeutic strategy and we can finally banish this type of nomenclature that may lead to error in the fulfillment of the objectives of the treatment of LNNL.3

Chronic renal disease: the largely forgottenIt seems that we continue to focus our thinking on the presence of CKD being exclusively linked to a GFR<60mL/min/1.73m2). However, nephrologists have known for some time that this is a misconception that has been reinforced by the recent KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) guidelines on CKD.13 The definition of CKD is obviously broader. We should include in the definition of CKD those patients who present with any of the following findings for at least three months: albuminuria greater than an albumin/creatinine ratio >30mg/g, persistent hematuria, lesions described on renal histology, and/or structural abnormalities detected by imaging. We believe that in the case of the patient with LN meets any of these criteria, so we should start saying that our patients with LN have CKD and focus our therapeutic strategies on prevention and nephro- and cardioprotection. Rojas-Rivera et al. in a very suggestive article published recently, highlight and insist on this concept of LN as CKD, forgotten by the different European and American guidelines, but which has a great impact on the cardiovascular health of patients with SLE.14

Complete remission, but where do we leave albuminuria?When we refer to complete remission in LN we talk of a proteinuria, ≤ 0.5g/24h or a urinary protein/creatinine ratio, ≤ 0.5g/g, inactive urinary sediment (≤5 red blood cells/field), a serum albumin ¡‚ ≥3.5g/dL and a normal GFR or ‚ ≤ 10% lower than that existing before the outbreak.7 However, a question arises about the patient with LN and in complete clinical remission: what should we the approach in a patient with proteinuria < 0.5g/24h, but with a pathological albuminuria? This question remains unresolved in the world of autoimmune diseases. We all would accept that pathological albuminuria in a diabetic patient is a factor that multiplies the cardiovascular risk and, therefore, we would intensify nephroprotective treatment,13 however, LN guidelines do not address this issue. Patients with SLE and even more so with LN are patients at high cardiovascular risk and presumably accelerated vascular aging, a reason why we should reconsider our therapeutic strategy in these patients and consider albuminuria as an argument to intensify our nephroprotective and cardioprotective treatment.14,15

From histological classes to indicators of activity and chronicityAccording to recent guidelines and recommendations including the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), KDIGO and Grupo de Enfermedades Glomerulares de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología (GLOSEN), we continue to focus our immunosuppressive treatment according to the histological class of the LN.16 However, nowadays we have a greater and better description of renal histology including activity and chronicity indexes that can help to decide the treatment. These types of indices can improve our therapeutic strategy, allowing us to select a specific immunosuppression or focusing more on nephroprotection. A recent publication makes us think about this possibility of focusing a personalized treatment for LN combining the activity index (AI) and the chronicity index (CI) together with the amount of proteinuria and the immunological activity of the patient with SLE. This approach would give a comprehensive integral view of the patient and to choose among our therapeutic options.17

What about the vascular lesion in renal biopsies?It is clear that we have improved our descriptions of renal biopsies thanks to the new 2018 classification, but there are still areas that need to be clarified, and one of them is the vascular lesion.18 More than a decade ago, a research group demonstrated that vascular injury was relatively frequent in biopsies of patients with LN and the type of vascular lesions was closely related to the evolution of renal function.19 In our experience with renal biopsies in patients with LN, vascular injury, rather than the change in histological class, was one of the most important risk factors for the development of CKD.20 In other systemic pathologies, such as diabetes mellitus, vascular damage is as important a risk factor in the development of CKD as glomerular injury.21 For this reason, we should request the inclusion in the renal biopsy report of a description of the vascular lesions. This type of lesion predicts the future evolution of renal function and possible cardiovascular events in our patients with LN and their premature vascular aging. It is crucial to develop research focused on the different cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the accelerated senescence observed in patients with CKD. Expanding our knowledge of the role of the factors and molecules involved in accelerated senescence will allow us to improve diagnostic and follow-up methods and will help us to identify possible therapeutic targets.22

Absence of a prognostic score in LNPresently, we do not have new biomarkers to establish the renal prognosis of patients with LN. Most studies use classical clinical, renal and histological markers. Systematic reviews highlight the great heterogeneity of studies in the definition of renal outcomes, which complicates risk stratification in these patients.23 In the up-coming years, we need to develop prognostic indices for the evolution of renal function that combine demographic, clinical, analytical and histological factors that are easy to apply in routine clinical practice and that become a diagnostic tool and a tool to be used for personalizing treatment.24 Furthermore, why not to propose a histological classification scoring system similar to that of IgA nephropathy (IgAN) that would allow prognosis of renal function evolution in patients with LN. Although it would have important limitations and biases, because LN is a more aggressive disease than IgA nephropathy, and any outcome study based on initial biopsy findings would be necessarily influenced by treatment, it could be an original way to analyze histological results.25

Glucocorticoid withdrawal, myth or reality?Although with some reluctance, it seems that we are ready for a world of autoimmune diseases without steroids. There is little experience in the suspension of glucocorticoids in patients with SLE and/or LN. A recent study by a French group with significant methodological limitations (single-center study, no biologic drug among the immunosuppressants used), concluded that maintenance with 5mg of prednisone prevented relapse in the patient with SLE.26 However, in this study it is noteworthy that 63% of patients did not relapse and remained glucocorticoid free. We believe that we are at an ideal moment to consider rapid reductions in glucocorticoids and even be able to discontinue them in a high and selected percentage of patients. This might be possible due to the treatments that there are available today (belimumab, rituximab, anifrolumab or calcineurin inhibitors). This new perspective would allow us to clearly reduce the accumulated organic damage resulting from the dose of glucocorticoids.

Immunosuppression, for how long?This is a controversial and complex issue due to the nature of the disease itself and the guidelines always leave some uncertainty “three to five years, after 12 months in remission”. However, this idea is diluted when we approach the real world. Studies such as MANTAIN (Mycophenolate Mofetil Versus Azathioprine for Maintenance Therapy of Lupus Nephritis), a 10-year analysis, showed that more than 50% of patients maintained some type of immunosuppression.27 Therefore, at this point, we could summarize the two most distant positions: those who are in favor of maintaining immunosuppression throughout life, based on the fact that this is an autoimmune disease that occurs in flares and lowering the immunosuppression could lead to relapses, which would deteriorate the patient's general situation. Conversely, others consider that after a reasonable period of immunosuppression (three to five years, after 12 months in remission), and in patients with exclusively renal involvement, immunosuppression could be withdrawn, based on the performance of a renal biopsy to decide whether or not to continue with immunosuppression, depending on the degree of activity.28

A French study has recently been published, in which patients with LN after two to three years of immunosuppressive treatment with mycophenolate or azathioprine in complete or partial remission were randomized to discontinue or maintain immunosuppression.29 After 24 months of follow-up, non-inferiority of discontinuation of maintenance immunosuppressive therapy was not demonstrated for renal recurrence (27.3 vs. 12.5%, the group that discontinued vs. that one with maintained immunosuppression. Discontinuation of immunosuppression was associated with an increased risk of severe SLE flare-ups. The end result of this study is that it raises further questions. To shed some more light on this point, Frangou et al. have proposed an algorithm regarding this controversy; maintain or gradually reduce until the immunosuppression is suspended in LN patients with in complete or partial clinical remission, after performing a renal biopsy.30 At this point and considering the available data, we should personalize this decision and take into consideration variables such as age, race, degree of SLE involvement (renal and extrarenal manifestations), recurrences, drug side effects, etc.31; these aspects should be placed on both sides of the scale, meanwhile let’s wait for new clinical trials that should shed more light on this therapeutic decision.

The use of Nephro-cardioprotective drugs in LN is not being valuated in clinical trialsIt is well known that patients with autoimmune diseases are excluded from all studies on new nephroprotective drugs.32 It means that to date there are no randomized clinical trials in autoimmune diseases testing nephroprotective and cardioprotective drugs. Thus, clinicians taking care of LN end up extrapolating the beneficial effects of these drugs in patients with SLE to the LN patients.33 Recently, we have published our experience with sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in patients with LN; its use resulted in a 50% reduction in proteinuria after eight weeks of treatment.34 The use of these drugs, together with the consideration of patient's histological findings, undoubtedly avoided the use of a greater amount of immunosuppression and made it possible to achieve the beneficial effect of these drugs. In addition, more and more drugs with great nephroprotective potential are becoming available (glucagon-like peptide type 1 [GLP1] receptor agonists, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, or endothelin antagonists) and we should evaluate in patients with LN whether the use of these drugs may help to improve the high cardiovascular comorbidity.

In conclusion, in the coming years we need to provide a more powerful response to all these questions in order to achieve better control of the disease, a lower incidence of side effects, decrease organ damage, and improve the quality of life of our SLE patients. It is time to reason.

FundingThis work has not received any funding.