Content

To the Editor:

Renal damage suffered in infancy in the haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (HUS) may determine long-term renal prognosis. We report a relevant case.

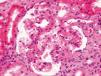

Our patient is a 33-year-old woman. When she was 9 months old, she suffered typical HUS that required acute peritoneal dialysis for 15 days, resulting in subsequent full recovery of renal function. She was discharged from consultations when she was 16 years of age. Since then, she has had no other relevant illness. Normotensive. She sought consultation due to progressive proteinuria with 5 years of evolution was determined by urine test strip. She is a woman of normal size, height 167cm, weight 67kg, blood pressure: 123/80. No oedema. The remainder was without findings. In complementary tests: CRP was 0.89mg/dl, creatinine clearance was 87ml/min, non-selective glomerular proteinuria was 292mg/dl (2.29g/d) urine analysis with absence of microhaematuria. Cholesterol was 252mg/dl. Total protein was 6.8g/d, albuminaemia was 4.0g/d. Complete blood count and angiotensin converting enzyme were normal. Immunology, thyroid profile and basic viral serology were negative. Renal ultrasound with kidneys showed a diameter of 97 and 95mm, with cortex of 13mm and 10mm and resistance index of 0.6 and 0.65. Immunoelectrophoresis of proteins in blood and urine and normal light chains. Computerised tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis without findings. Mantoux test negative. Renal biopsy was performed, revealing 7 glomeruli: 1 sclerotic, 4 normal and 2 with signs of focal segmental hyalinosis (Figure 1). Immunofluorescence: negative. Electron microscopy: not performed. Treatment was started with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors with reduction in proteinuria at 3 months to 1 g/d and glomerular filtration stability.

In childhood HUS, the number of affected capillaries determines long-term glomerular damage by developing glomerular hyperfiltration (GHF). Many articles1-5 recognise this fact. Garg et al.6 include 49 studies, 3476 patients with a mean follow-up period of 4.4 years (1 to 22), patients from 1 month to 18 years old. It shows a combined incidence of mortality/end-stage renal failure (ESRF) of 12%. 64% displayed renal complications (defined as high blood pressure [HBP], a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate [GFR] <80ml/min and/or significant proteinuria), with a combined incidence of 25%. 15% had proteinuria, 10% HBP and there was a 15.8% drop in GFR. The long-term prognosis was worse in those who suffered cortical necrosis and who required renal replacement therapy for longer than 8 days. Between 8% and 61% of those who had fully recovered renal function suffered renal complications that even began 20 years later.

Moghal et al.7 biopsied 7 normotensive patients with complete recovery of renal function and late damage, with the following result: overall glomerulosclerosis (85.7%), segmental sclerosis lesions (28.6%), tubular atrophy (14%) and overall glomerulomegaly with intimal thickening of small vessels (100%).

Caletti et al.8 biopsied 30 children with renal complications with 11.2 years evolution. They found 56.6% of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with hyalinosis, 30% of diffuse mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN), 6.6% of GN with minimal changes and 6.6% of diffuse glomerulosclerosis. The findings were interpreted as mesangial GN followed by focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with hyalinosis culminating in diffuse glomerulosclerosis. After follow-up, only 25% of the latter had a normal GFR.

Tönshoff et al.9 studied 89 patients after 16 years. 10.4% progressed to advanced chronic renal failure (CRF) and 3% to ESRF.

Gagnadoux4 followed up 29 patients for 15-28 years. 41.4% had sequelae, 10.3% progressed to CRF and 13.8% to TRF between 16 and 24 years after it started. 6.9% had normal GF at 10 years and developed CRF after this time.

Kelles et al.5 followed up 95 patients for 10 years and found that 65% did not suffer sequelae, 26% had mild renal disorder and 9% had progressed to severe CKD.

In all series, the possibility of progression was greater if they suffered mesangial GN.

These data coincide with the possibility of developing late renal failure after suffering pre-eclampsia in pregnancy.10 In both cases, a noxa, self-limiting in time determines functional renal sequelae in the very long-term.

In our case, the histology ruled out the possibility of primary glomerulopathy. In spite of the short follow-up time, we found a significant decrease in proteinuria, giving the patient a good renal function prognosis.

This case illustrates that a typical epidemic HUS in children may cause renal failure, HBP and proteinuria. These complications may even begin 20 years after the illness has been considered cured. As such, we indicate long-term follow-up of these patients. Treatment should be aimed at controlling risk factors that accentuate GHF (obesity, HBP) and specifically inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Kidney biopsy