Galicia has one of the highest incidences of tuberculosis (TB) of any of the autonomous communities of Spain, which is even higher in patients on renal replacement therapy (RRT).1,2

In 2019, a plan was designed for the prevention and control of TB in Spain,3 which stresses the importance of reinforcing the identification of latent tuberculosis infection (LTI) in certain groups of patients, including patients on RRT and, fundamentally, those on the kidney transplant waiting list.

We carried out a study of the prevalence of LTI in patients on RRT, both on haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD), by performing the tuberculin test (TT) and the Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) tuberculosis test, if the TT negative. If the TT or IGRA were positive, patients were evaluated by the tuberculosis unit (TBU) which, after ruling out active TB, with the tests that they considered appropriait was de decided whether or not to start chemoprophylaxis.

We evaluated 209 patients, seven of which were excluded due to having previously suffered from active TB. Of the remaining 202, 70.29% were on HD.

In patients on PD, 18.3% had TT+ compared to 12.7% on HD.

Patients who were TT− were given an IGRA test, which was positive in 18.8% of patients on HD and 11.8% in patients on PD.

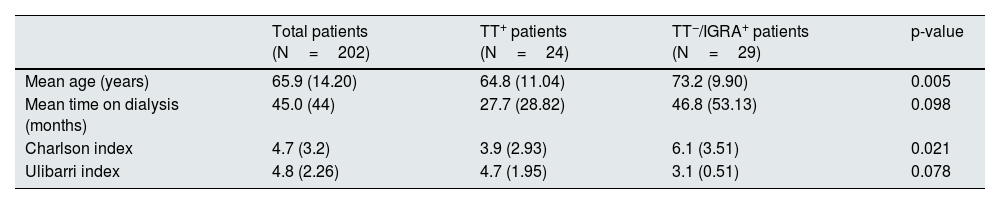

Patients with LTI were classified into two groups: those TT+; and those TT− and IGRA+. The second group were older patients, with a longer time on dialysis and with a higher Charlson index (CI).

A total of 53 patients had LTI. Eleven cases (20.75%) did not receive treatment, either due to excessive associated comorbidity or patient refusal. Thirty-seven cases (69.81%) completed the prophylaxis treatment according to the TBU protocol, without notable side effects, and at the end, treatment had to be abandoned in five cases (9.43%) because of side effects.

The demographic characteristics and results are shown in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and study results.

| Total patients (N=202) | TT+ patients (N=24) | TT−/IGRA+ patients (N=29) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 65.9 (14.20) | 64.8 (11.04) | 73.2 (9.90) | 0.005 |

| Mean time on dialysis (months) | 45.0 (44) | 27.7 (28.82) | 46.8 (53.13) | 0.098 |

| Charlson index | 4.7 (3.2) | 3.9 (2.93) | 6.1 (3.51) | 0.021 |

| Ulibarri index | 4.8 (2.26) | 4.7 (1.95) | 3.1 (0.51) | 0.078 |

IGRA: Interferon Gamma Release Assay tuberculosis test; LTI: latent tuberculosis infection; TT: tuberculin test.

Charlson index: relates long-term mortality to patient comorbidity. 0–1 point: absence of comorbidity; 2 points: low comorbidity; >3 points: high comorbidity.

Ulibarri index: assessment of the patient's degree of malnutrition. 0–1: no malnutrition; 2−4: mild malnutrition; 5−8: moderate malnutrition; >8: severe malnutrition.

During follow-up, three patients developed TB, all extrapulmonary; six months after completing prophylaxis, one of these patients on the PD programme developed peritonitis with a negative culture and was diagnosed with miliary TB. Another patient on HD who was TT− and IGRA+, interpreted as LTI, developed a pericardial effusion with haemodynamic compromise a few weeks after starting prophylaxis. Although there was no microbiological diagnosis, after antituberculosis treatment, which he completed successfully, produced a significant clinical and radiographic improvement.

A patient on HD who stopped chemoprophylaxis after developing a severe rash had to be admitted to hospital with pericardial effusion and constitutional syndrome. The clinical, laboratory and radiological data were consistent with TB, although it could not be confirmed histologically. In accordance with the TBU, he was started on antituberculosis treatment, with clear clinical improvement.

In patients on RRT, the combination of TT and IGRA is required to diagnose LTI, particularly in older adult patients who have been on dialysis for longer and have greater comorbidity, because in this group TT performs poorly.4–6

Prior to starting prophylaxis, active disease must be ruled out, particularly in patients on the kidney transplant waiting list.7 It is important to remember that in patients on dialysis, TB is generally extrapulmonary,8 therefore a simple chest X-ray or sputum cultures may not be sufficient to make the diagnosis. A high degree of clinical suspicion is essential to come up with a diagnosticsince histological diagnosis is not always possible, as was the case in our patients. The post-treatment clinical and radiological improvement they experienced supported the diagnosis of active TB.

Ruling out LTI in patients on the kidney transplant waiting list is necessary. Patients IGRA− pre-transplant have a very low risk of subsequently developing active TB.9 If necessary, this screening and treatment should preferably be performed in the advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) clinic.

Chemoprophylaxis in patients on RRT or being followed in the ACKD clinic who are not going to be included in the kidney transplant waiting list should be considered on an individual basis, assessing risk-benefit based on the associated comorbidity in each case.10