To the Editor:

We present a case of nonocclusive ischaemic colitis in haemodialysis (HD) with a good response to conservative treatment.

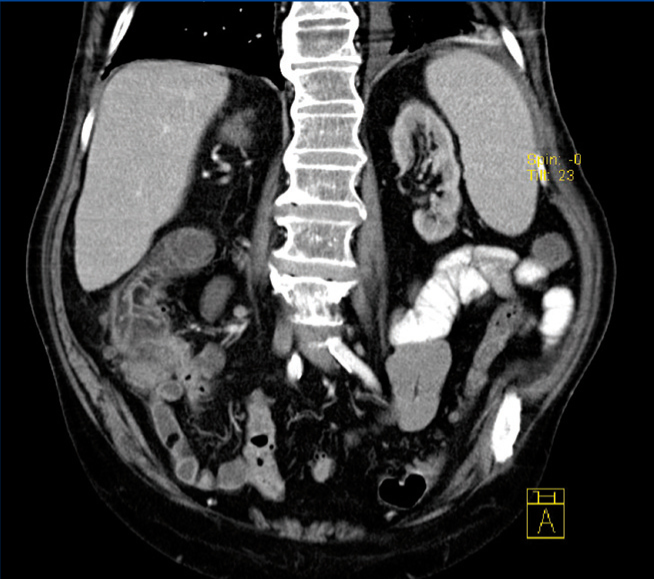

An 81-year-old male with high blood pressure, class II obesity, chronic ischaemic heart disease, severe hyperparathyroidism and end stage renal disease due to nephrosclerosis on HD for two months. He presented with acute coronary syndrome and atrial flutter requiring a coronary catheterisation with transcutaneous revascularisation. He was treated with clopidogrel, carvedilol, amiodarone, transdermal nitroglycerin, esomeprazole, paricalcitol and epoetin alpha, to which acenocoumarol was added. After 15 days, he developed severe intradialytic hypotension and 24 hours later, he experienced abdominal pain and hypotensive syncope with rectal bleeding and he required hospitalisation. The blood test results displayed: haemoglobin: 7.7g/dl, leukocytes: 10.50 10e3/µl, INR: 3.23, CRP: 315.7mg/l and the rest was normal. A computerised tomography was carried out on the abdomen, displaying severe calcific atherosclerosis of the aorta with an absence of occlusion in mesenteric arteries, diffuse oedema of the terminal ileum, ascending colon and caecum submucosa, and pneumatosis intestinalis (Figure 1). He became haemodynamically stable and we administered parenteral nutrition and broad-spectrum antibiotics. After 9 days, he developed a second episode of rectal bleeding. A colonoscopy was carried out and it displayed extensive fibrinous necrotic plaque in the caecum and mucous haemorrhagic suffusions in the ascending and transverse colon. He remained in hospital for 60 days and he lost 16kg during this period. He was discharged with intradialytic parenteral nutrition, which was maintained for three months. His weight stabilised and his total protein and albumin of 4.9g/dl and 1.8g/dl at the time of discharge increased to 7.1 and 3.8g/dl after six months. Twenty-four months later, he remained on oral supplements and maintained nutritional stability. Another computerised tomography of the abdomen was performed and we observed the disappearance of lesions in the right colon and residual pneumatosis in the ileum. A study of faeces that ruled out protein losing enteropathy was carried out.

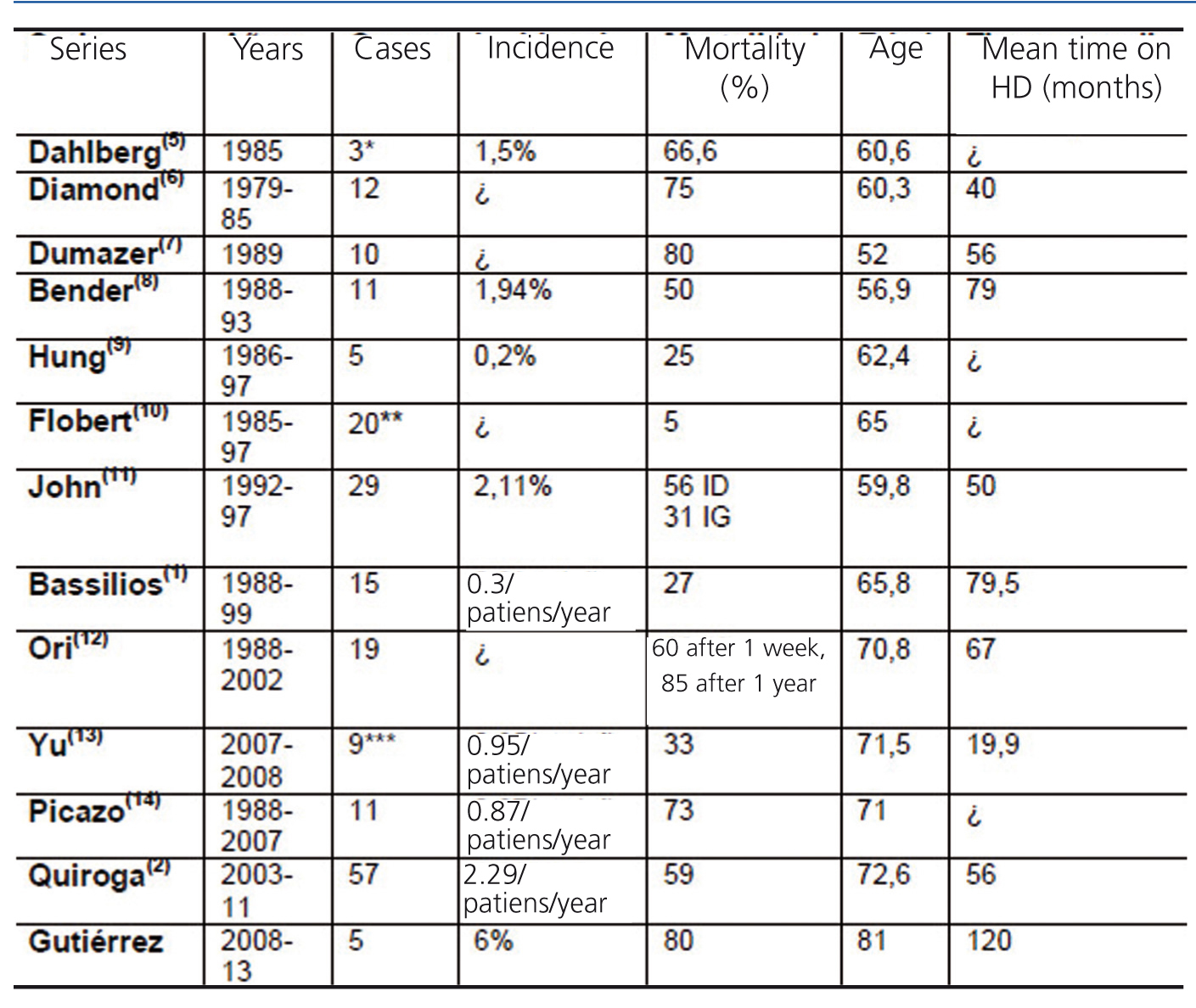

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischaemia represents 25%-40% of cases of intestinal infarction and 9% of the causes of death in HD. The incidence in non-haemodialysis patients is 0.09-0.2 episodes/patient/year, 0.3-1.9 episodes/patient/year in series prior to 20051 and 2.29 episodes/patients/year in more recent years,2 although in retrospective studies with computerised tomography of the abdomen and autopsies on HD and peritoneal dialysis patients3,4 the incidence was 18.1% and 14%, respectively. The most vulnerable anatomical areas were Griffiths’ point, Sudeck's point and the Drummond marginal artery. The colon is the most vulnerable segment due to its low cardiac output and high reflex vasoconstriction capacity. The mucous hypoperfusion lesion occurred in 1 hour and transmural infarction in 8-16 hours. In accordance with the severity of involvement, we can identify five stages: reversible colopathy and transient colitis (50% of cases), which are resolved ad integrum and segmental ulcerative colitis, gangrenous necrosis and fulminant pancolitis (more than 90% mortality), which progress to segmental ulceration with stenosis, perforation, gangrene and sepsis. Segmental ulcerative colitis may clear up within six months, although a proportion of patients maintain bloody diarrhoea, protein-losing colopathy, segmental stenosis and recurrent sepsis. In non-haemodialysis patients, symptoms usually appear after occlusive ischaemia of the left colon and sigmoid. In HD, younger patients are affected in the right colon (82%), with more severe lesions and more bleeding, always preceded by a trigger, mainly severe hypotension. Risk factors include advanced age, diabetes mellitus, vascular calcification, more time on HD, vascular access thrombosis, the use of diuretics, vasopressor drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Early surgical treatment improves prognosis. In our hospital, out of a total of 83 patients dialysed since 2008, we have had 5 cases, and the aforementioned patient is the only one who survived. The other four (one male and three females) died in the first week of progression. Symptoms appeared in patients with a mean age of 81 who had been on HD for a long time (mean 10 years) and as a result of a long progression of atherosclerotic disease and vascular calcification with severe ischaemic heart disease treated by revascularisation, with arrhythmias in the 4 cases, 2 with permanent pacemakers and 1 with a long-term aortic prosthesis, which makes us consider ischaemic colitis to be the last frontier of vascular involvement facing these patients. Given the progression in age, time on HD as exemplified by the main series (Table 1) and calcification in patients, nonocclusive ischaemic colitis may be a progressive source of morbidity in HD, with increased incidence, and we will be able to confirm this in the coming years.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Case series

Figure 1. Computerised abdomen tomography