The thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TAL) reabsorbs approximately 30% of filtered NaCl through two mechanisms: transepithelial and paracellular reabsorption. The latter is carried out through a class of tight junction proteins known as claudins. A mutation in the gene encoding claudin-10 causes a rare salt-wasting tubular disorder with hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. However, unlike Bartter syndrome and Gitelman disease, it usually presents with hypermagnesemia and extrarenal manifestations such as xerostomia, alacrima, and hypohidrosis with ichthyosis, known by the acronym HELIX syndrome.

La rama gruesa ascendente del asa de Henle (TAL) reabsorbe aproximadamente el 30% de NaCl filtrado mediante dos mecanismos: reabsorción transepitelial y paracelular. Esta última se efectúa a través de un tipo de proteínas de las uniones estrechas conocidas como claudinas. La mutación en el gen que codifica la claudina 10 ocasiona un raro trastorno tubular, pierde sal, con alcalosis metabólica hipopotasémica, pero que a diferencia del síndrome de Bartter y enfermedad de Gitelman, suele cursar con hipermagnesemia y con manifestaciones extrarrenales como xerostomía, alacrimia e hipohidrosis con ictiosis conocido con el acrónimo de síndrome de HELIX.

The thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TAL) plays a fundamental role in the physiology of the human kidney by participating in the reabsorption of sodium; the mechanisms underlying urine concentration; the homeostasis of calcium, magnesium, bicarbonate and ammonium; and the synthesis of uromodulin by regulating the composition of urinary proteins.1

The TAL reabsorbs approximately 30% of the filtered NaCl via 2 mechanisms: transepithelial and paracellular reabsorption. Transepithelial reabsorption depends on the joint action of 2 apical proteins (cotransporter NKCC2 (Na+-K+-2Cl–) and potassium channel (Ki1.1)) and 4 basolateral proteins (Na-K-ATPase; chloride channels CLC-Ka and ClC-Kb; and its bartine subunit).2,3 The paracellular pathway, which is responsible for the reabsorption of almost 50% of sodium, is promoted by a lumen-positive transepithelial potential and is regulated by a type of claudin known as claudin-10b.1,4 Claudins are a family of integral transmembrane proteins that are part of the tight junctions of epithelial and endothelial cells and play crucial roles in controlling the paracellular transport of ions, water and other small molecules. In the kidney, each tubular segment expresses a specific set of claudins that confer unique properties in terms of permeability and selectivity of the paracellular pathway, in addition to contributing to the maintenance of cell polarity.4

Claudinopathies are hereditary disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding claudins and lead to diseases such as familial hypomagnesemia syndrome with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis (involving claudins-16 and 19)5; nonsyndromic autosomal recessive sensorineural deafness (involving claudin-14)6; and neonatal ichthyosis-sclerosing cholangitis (involving claudin 1).7 Certain polymorphisms in the gene encoding claudin 14, (through its interaction with claudin-16, have been associated with the development of hypercalciuria and renal calculi.8

Most tubular disorders that involve salt-wasting with activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), which affects the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), such as Bartter’s syndrome and Gitelman’s disease, respectively, involve hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis and hypomagnesemia. Here, we describe the case of a patient with a salt-wasting tubulopathy phenotype but with the characteristic finding of elevated plasma magnesium levels.

Case reportA 2-year-old male of Colombian origin was referred to the pediatric nephrology clinic for the confirmed accidental finding of an elevated creatinine level (Cr: 0.47 mg/dl) detected in the context of a study of psychomotor developmental delay. No consanguinity was reported. Moreover, there was no contributing family history, except for a maternal grandfather who died of chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology. Upon examination of the patient’s health history, an external benign hydrocephalus diagnosed via brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as a cutaneous xerosis with slight desquamative ichthyosis, anhidrosis and decreased production of saliva managed by dermatology, were notable (without wearing of the tooth enamel or gingival inflammation being observed). There was no delay in weight or height observed (weight: 11.5 kg [Z score: −0.48]; height: 87 cm [Z score: −0.26]).

From a clinical point of view, the patient presented symptoms of polyuria-polydipsia, with no other clinical abnormalities. There was no history of consumption of nephrotoxic drugs or urinary tract infection. Additionally, the absence of macroscopic hematuria was noted.

The following laboratory findings regarding renal function were reported: urea concentration of 45 mg/dl, creatinine concentration of 0.47 mg/dl, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (Schwartz_09) of 76 ml/min/1.73 m2, Na concentration of 135 mEq/l, K concentration of 3.8 mEq/l, Cl concentration of 98 of mEq/l, Ca concentration of 8.9 mg/dl, P concentration of 6.3 mg/dl, Mg concentration of 4.8 mg/dl, uric acid concentration of 5.4 mg/dl, fractional excretion of sodium (EFNa) of 0.9%, tubular reabsorption of phosphate (RTP) of 90%, fractional excretion of potassium (EFK) of 21.37%, fractional excretion of magnesium (EFMg) of 1.98%, Ca/Cr ratio of 0.02 mg/mg, pH of 7.42, bicarbonate concentration of 26.6 mmol/l, and base excess (BE) concentration of 1.9 mmol/l. No abnormalities were observed in the urinary sediment. Moreover, the urine concentration after the administration of desmopressin was determined to be 661 mOsm/kg. A normotensive status was observed. Renal ultrasound revealed no pathological findings, as well as the absence of nephrocalcinosis.

Given the suspected diagnosis of chronic kidney disease of probable tubulo-interstitial etiology, a genetic study was requested involving an exome sequencing panel targeting tubular disorders and autosomal dominant tubulo-interstitial nephritis (TADN), which yielded negative results.

During outpatient follow-up, a salt-wasting tubulopathy with a Gitelman disease phenotype was observed, characterized by the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (renin level: 467 μU/ml and aldosterone level: 621 pg/ml), hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.41, bicarbonate level 26: mmol/l, and K level: 2.57 mEq/l) and hypocalciuria (0.02 mg/mg), but unlike Gitelman’s disease, with hypermagnesemia (5.1 mg/dl) without any reported symptoms suggestive of this condition. Given the clinical picture described, in conjunction with the extrarenal manifestations of xerosis with desquamative ichthyosis and anhidrosis, a genetic study of claudinopathy was recommended. The study detected a pathogenic variant (variant c.316_323delGGCTCCGA, p. [Gly106*]) in exon 3a of the CLDN-10b gene in apparent homozygosis, compatible with HELIX syndrome.

A familial segregation study was recommended; however, only the mother provided consent, and analysis revealed that the investigated variant was not detected, which suggested the appearance of a de novo mutation in the patient without the ability to exclude the existence of consanguinity in the progenitors.

The treatment required sodium supplements (sodium chloride: 3 mEq/kg) and potassium (potassium chloride: 2.5 mEq/kg), as well as abundant water intake. The patient did not require treatment for hypermagnesemia.

Currently, at the age of 8 years, the patient exhibits an adequate weight–height curve with a GFR (Schwartz_09) of 81 ml/min/1.73 m2 and the previously described electrolyte alterations. He also presented with a slight global developmental delay in follow-up conducted by neuropediatrics, as well as xerosis and anhidrosis in the follow-up performed by dermatology.

DiscussionThe syndrome of hypohidrosis, electrolyte disturbances, lacrimal gland dysfunction, ichthyosis, and xerostomia (HELIX) is a rare hereditary tubular disorder involving a loss of salt, with renal and extrarenal manifestations, which was named by Hadj-Rabia et al. in 2018,9,10 although it was previously described as a new tubular disorder in 2017 by Bongers et al.11

From a renal aspect, the manifestations are a consequence of a reduction in the paracellular permeability of sodium in the thick ascending portion of the loop of Henle, which results in a scenario of polyuria-polydipsia due to hydrosaline loss, with a defect in the ability to concentrate urine, along with electrolyte alterations, which include hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis due to secondary hyperaldosteronism, in addition to a tendency toward low blood pressure, hypermagnesemia, hypercalcemia with hypocalciuria and slow progression to chronic kidney disease.1,9–11

Moreover, the extrarenal manifestations affect the exocrine glands and are characterized by xerostomia with a severe reduction in the aqueous component of saliva, severe enamel wear, alacrima, hypohidrosis with heat intolerance and ichthyosis.1,9–11

HELIX is an autosomal recessive hereditary disorder that requires a homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation in the claudin-10 gene located on chromosome 13 (13q.31.-q.34).9–11 This gene contains 6 exons and gives rise to 2 isoforms (claudin-10a and claudin-10b) that differ in exon 1.12 The described mutations can affect both isoforms, as well as claudin-10b alone; however, no differences in their clinical manifestations are detectable.12 Claudin-10a, which acts as a paracellular anion channel (Cl−), is restricted to the uterus and kidney (specifically in the proximal convoluted tubule).13,14 Conversely, claudin-10b is the only claudin that is present in the inner strip of the external medulla (ISOM); however, in the outer strip of the external medulla (OSOM) and in the cortex, the claudins demonstrate a similar pattern of mosaic expression, with tight junctions that express claudin-10b and claudins-3, 14, 16 and 19, which are responsible for the reabsorption of cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ 1915. Claudin-10b is a channel that is impermeable to water but highly permeable to Na+, thereby contributing to the dissipation of the positive transepithelial potential in the tubular lumen of the TAL.4,12,14,15 In addition to being present in the kidney, claudin-10b is located in the salivary glands, sweat glands, brain, lungs and pancreas.4,12

In 2012, Breiderhoff et al. investigated a mouse model lacking the expression of claudin-10 in the loop of Henle and reported that a reduction in the paracellular selectivity of Na+ in the TAL led to a defect in urinary concentration with polyuria, polydipsia and elevated levels of urea, accompanied by an increase in the secretion of K+ and H+ as well as hypermagnesemia. These electrolyte alterations were accompanied by severe medullary nephrocalcinosis.16

From a pathophysiological point of view, the loss of function of claudin-10b reduces the reabsorption of Na+ in the TAL via the paracellular component, thus increasing the lumen-positive transepithelial potential, which favors the paracellular reabsorption of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the TAL through a redistribution of claudin-16 and claudin-19 in the tubule segments1,12,16,17 (Fig. 1). As occurs with other salt-wasting tubulopathies that affect the TAL (such as Bartter’s syndrome), the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, as well as the distal supply of Na+, favors the reabsorption of Na+ through the sensitive receptor to amiloride (ENaC, which is regulated by aldosterone) of the principal cells, as well as the secretion of K+ and H+ by the intercalated cells of the distal segment of the nephron, thus leading to the electrolyte disorder characteristic of hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. Conversely, in the epithelium of the salivary, sweat and lacrimal glands, Na+ and Cl− are secreted through the basolateral cotransporter NKCC1 and the apical chloride channel CFTR, thereby creating a lumen-negative transepithelial potential differential that allows for the passive paracellular secretion of Na+ through claudin-10b, which acts as a channel. This phenomenon is associated with transcellular water secretion through aquaporin-5 water channels. The loss of function of claudin-10b results in a defect in the secretion of Na+ and water, with the previously described extrarenal manifestations.1,12

Speculative model of the pathophysiology of Helix syndrome in the thick ascending loop of Henle. Reabsorption of Na+, 2Cl− and K+ through the furosemide-sensitive transporter (NKCC2); the recycling of K+ in the apical membrane (kir1.1); and the return of Na+ from the interstitial space to the tubular lumen through tight intercellular junctions contribute to the development of a lumen-positive transepithelial electrical gradient, which favors the paracellular passage of Ca2+ and Mg2+ through claudin-16 and claudin-19. Cl− crosses the basolateral membrane through the ClC-Ka and ClC-Kb transporters, whereas Na+ crosses this membrane through the Na+-K+ ATPase pump coupled to the entry of K+ into the cell interior. In this way, a chemical gradient necessary for the reabsorption of Na+ through the NKCC2 cotransporter is generated. Certain cells of the loop of Henle express a claudin-10b protein, which is responsible for the paracellular reabsorption of Na+ and the dissipation of the lumen-positive transepithelial electrical gradient. Therefore, its dysfunction reduces the paracellular reabsorption of Na+, thus increasing the lumen-positive transepithelial potential, which is responsible for the increase in the reabsorption of Ca2+ and Mg2+ through the redistribution of claudin-16 and claudin-19. Ca2+: calcium; Cl−: chloride; K+: potassium; Mg2+: magnesium; Na+: sodium. Gr1.

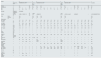

Currently, 37 cases of this disorder involving 11 families have been described.9,18–22 This publication is the first to describe the characteristics of pediatric patients with this syndrome. Table 1 shows the main genetic, clinical and analytical data of the pediatric patients, including our patient. The ages ranged from 1 year to 18 years. Given the inheritance pattern reported for this disease, most patients have a history of consanguinity, except for our patient, for whom consanguinity could not be confirmed. All of the patients (except for one patient) had a homozygous missense mutation. From a clinical point of view, the extrarenal manifestations of the disease were exhibited in all patients, although severe heterogeneity was noted. Although no data have been published regarding the urinary concentration capability, a defect in the ability to concentrate urine is relatively common and may be due to salt loss, which prevents the creation of adequate tonicity of the medullary interstitium, as well as chronic hypokalemia. Hypermagnesemia is a common finding in all pediatric patients, and its frequency decreases with age. In a significant proportion of patients, potassium concentrations were observed to be within normal ranges; however, it is necessary to note that hypokalemia is more frequently observed in adults than in children, which is likely a consequence of the compensation mechanism that exists in children despite the activation of the renin–aldosterone axis. In patients in whom the acid-base balance was evaluated, metabolic alkalosis with low blood pressure and hypocalciuria was observed, as was described in our patient. The frequency of chronic kidney disease described in adults is as high as 25% of cases12,18; however, it was relatively common in the investigated pediatric patients. The underlying pathogenic mechanism in adults could be related to inflammation of the interstitium with vasoconstriction and increased fibrosis secondary to chronic hypokalemia23,24; however, more studies are needed in children. Additionally, albuminuria was a finding described in some patients of the series, as was observed in our case. On renal ultrasound, no abnormalities in the size or echogenicity of the kidneys o were detected, nor was nephrocalcinosis, in contrast to the findings observed in the investigated mouse model.12,16

Demographic, genetic, clinical and analytical data of pediatric patients diagnosed with HELIX syndrome.

| Studies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bongers et al., 201711 | Hadj-Rabia et al., 201810 | Meyers et al., 201918 | Alazaharani et al., 202119 | Sewerin et al., 202220 | Qudair et al., 202321 | This article | ||||||||||||||||||

| Families | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 7.1 | ||||||||||||

| Consanguinity | ↓ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No* | ||||||||||||

| Sex | M | F | F | F | M | M | M | F | M | F | M | F | F | M | M | F | F | M | M | F | M | M | M | |

| Age | 15 | 14 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 3 | 17 | 15 | 12 | 16 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 2 | |

| 18 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Genotype | Compound heterozygote | Homozygote | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Variants | c.446C> | c.386C > T c.392C > T/4 | c.2 T > C/2 | c.232A > G | c.653delC/10 | c.494 G > C | c.138 G > A novel/3 | c.653delC/5 | ↓ | c.316_323delGGCTCCGA | ||||||||||||||

| c.217 G > A/1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clinic | Renal | ↓ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||||||

| Extrarenal | ↓ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||

| PA | N | N | N | ↓ | – | ↓ | ↓ | N | ||||||||||||||||

| Plasma values | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Na+ (mEq/l) | ↓ | 137 | 141 | 137 | 139 | ↓ | 141 | 138 | 139 | 139 | 137 | 140 | 141 | 137 | 139 | 140 | 138 | ↓ | 137 | 137 | 138 | 140 | 137 | |

| K+ (mEq/l) | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 6.9 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 4 | 5.8 | ↓ | 3.4 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 2.57 | |

| 2.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cl− (mEq/l) | ↓ | 97 | 105 | 101 | 108 | ↓ | 92 | 94 | 97 | 101 | 101 | 103 | 103 | 88 | 100 | 103 | 105 | ↓ | 97 | 98 | 100 | 98 | 97 | |

| Protein (g/dl) | ↓ | 7.4 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 7.2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 7.62 | |

| Ca2+ (mg/dl) | 2.59 | 9.36 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 9.2 | ↓ | 9.9 | 8.94 | 9.1 | 9.14 | 9.14 | 9.38 | 9.5 | 4.73 | 9.74 | 9.82 | 9.74 | 8.82 | 9.7 | 9.94 | 10.5 | 9.22 | 9.4 | |

| 2.59 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mg2+ (mg/dl) | 1.03 | 3.19 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 5 | ↓ | 2.75 | 5.15 | 3.33 | 3.48 | 2.38 | 2.48 | 2.16 | 2.53 | 2.82 | 2.97 | 3.62 | 4.33 | 3.6 | 3.91 | 3.62 | 3.33 | 5.1 | |

| 0.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| pH | 7.51 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 7.486 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| 7.42 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HCO3− (mmol/l) | 30.1 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 36 | 25 | 23 | 22 | ↓ | 30 | 26 | 24 | 29 | ↓ | |

| 28.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 90 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.82 | 0.58 | 0.4 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.27 | ↓ | 1.24 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.48 | |

| 88 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (microM) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FG (ml/min/1.73 m2) | >90/149 | 83 | 84 | 55 | 118 | 101−59 | 183 | ↓ | 94.6 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 73 | |

| >90 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Renin (pg/ml) | ↓ | 56 | 130 | 100 | 83 | ↓ | 401 (mU/l) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 531 (mU/l) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 467 | |

| Aldosterone (ng/dl) | ↓ | ↓ | 19.7 | 36.6 | 17.5 | ↑ | 37.42 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 30.86 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 621 | |

| Urine values (Isolated sample) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 84 | <60 | 105 | 129 | 185 | 203 | 26.8 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 85 | 98 | 70 | 85 | ↓ | 124 | |

| K+ (mEq/l) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 60 | 85 | ↓ | 38 | 67 | 115 | 28.2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 27.8 | 28.09 | 54.6 | ↓ | ↓ | 43 | |

| Ca2+ (mmol/l) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | <0.2 | <0.2 | <0.5 | 0.32 | <0.2 | 0.85 | 0.48 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | <0.2 | <0.2 | <0.2 | ↓ | 0.12 | |

| Mg2+ (mmol/l) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 2.14 | 3.1 | 2.05 | 3.93 | 3.02 | 5.07 | 1.86 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 2.25 | 2.43 | ↓ | ↓ | 2.02 | |

| EFK (%) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 21.37 | ||||||||||

| 36 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EFMg (%) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 1.98 | ||||||||||

| 5.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Albumin/Cr (mg/g) | ↓ | ↓ | 206 | 175 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 126 | ||||||||||

| Protein/Cr (mg/mg) | ↓ | ↓ | 0.41 | 0.41 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 0.44 | ||||||||||

The studies are represented in the first row in chronological order (1 - Bongers et al., 201711; 2 - Hadj-Rabia et al., 201810; 3 - Meyers et al.,18; 4 - Alzaharani et al.,19; 5 - Sewerin et al.,20; 6 - Qudair et al.,21; 7 - This article. 2025). The families of each study are represented in the second row. F: female; M: male; (↓): not available; BP: blood pressure; N: normal; ↓: low; ↑: high; No*: it is not possible to rule out consanguinity; Ca2+: calcium; Cl−: chloride; Cr: creatinine; EFMg: fractional excretion of magnesium; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; HCO3−: bicarbonate; K+: potassium; Mg2+: magnesium; Na+: sodium.

The definitive diagnosis of this syndrome is achieved via genetic tests involving sequencing of the described gene, which is essential for genetic counseling. Renal biopsy is not needed.

There is no specific treatment to improve the conditions of patients with HELIX syndrome. High intake of NaCl and fluids is recommended, along with the utilization of potassium supplements and drugs that block the secretion and/or action of aldosterone or epithelial Na+ channel blockers (ENaCs) when refractory hypokalemia occurs. Artificial tears and saliva can be used to relieve the symptoms of dry eyes and dry mouth, respectively. Prolonged intense physical activity should be discouraged (particularly when the external temperature is high) to prevent the risk of hyperthermia.

The authors present no conflicts of interest.