The key points of a monographic vascular access (VA) consultation are an adequate preoperative assessment, as well as a correct management and optimization of waiting lists. Our main objective of present study was to evaluate the degree of exploratory-dependent concordance in outpatient clinics regarding implanted VA, between nephrology and vascular surgery.

Materials and methodsWe analyzed VA created or surgically repaired between 2021 and 2022. We compared the differences in the preoperative variables between the groups in which the assessments between the two teams were coincident and non-coincident, and the primary (PP) and secondary (PS) patencies during the follow-up period (Kapplan-Meier curves and Log-rank test, and Cox regression analysis). Significant P ≤ 0.05.

ResultsA total of 605 VA creations or repairs were analyzed: 74 ligations (12.2%), 207 distal arterio-venous fistulaes (AVF) (34.3%), 237 proximal AVF (39.2%), 35 repairs (5.7%), 41 grafts (6.7%) and 11 others (1.9%). After an average waiting list time of 16.5 ± 11.6 days, excluding ligations, adequate 1-month maturation was observed in 87.6% of cases. A total of 158 endovascular procedures and 17 surgical repairs were performed during postoperative follow-up. Primary (PP) and secondary (PS) patencies at 6, 12 and 24 months were PP: 76.2%, 64.9%, 57.5% and PS: 86.4%, 81.2%, 74.7%, respectively. Of the total number of procedures, nephrology obtained an adequate degree of agreement in 93.6% of the cases (kappa index: 0.886). The preoperative factors associated with greater discrepancies in assessments were age (P = 0.022) and arterial diameter (P = 0.032). The subgroup of non-matched assessments between nephrology and vascular surgery (39 cases) presented a similar PP (at 2 years: 59.2% vs 41.3%, P = 0.099) but worse PS (at 2 years: 76.6% vs 55.4%, P = 0.005).

ConclusionsNo significant observer-dependent differences (nephrologist vs. vascular surgeon) were observed in decision-making regarding the surgical procedure to be performed (93.6% agreement), and discordant cases presented worse secondary patency. After specific training, the nephrology coordination team can make a proper optimisation of social and health resources by reserving referrals to vascular surgery for those cases of greater complexity.

Entre los puntos clave de una consulta monográfica de acceso vascular (AV) se encuentran una adecuada valoración preoperatoria, así como una correcta gestión y optimización de las listas de espera. El principal objetivo fue evaluar el grado de concordancia explorador-dependiente entre nefrología y cirugía vascular en una consulta externa monográfica respecto al AV finalmente implantado.

Material y métodosSe analizaron todos los AV creados o reparados quirúrgicamente entre los años 2021 y 2022. Se comparan las diferencias en las variables preoperatorias entre los grupos en los que las valoraciones entre ambos equipos fueron coincidentes y no coincidentes, la cirugía indicada y la permeabilidad primaria (PP) y secundaria (PS) durante el período de seguimiento (curvas de Kapplan-Meier y Log-rank test, y análisis de regresión de Cox). P significativa ≤ 0.05.

ResultadosSe han analizado un total de 605 creaciones o reparaciones de AV: 74 ligaduras (12.2%), 207 FAVn distales (34.3%), 237 FAVn proximales (39.2%), 35 reparaciones (5.7%), 41 FAVp (6.7%) y 11 otros procedimientos (1.9%). Tras un tiempo medio en lista de espera de 16.5 ± 11.6 días, excluyendo las ligaduras, se observó una adecuada maduración al mes en el 87.6% de los casos. En el seguimiento postoperatorio se realizaron un total de 158 procedimientos endovasculares y 17 reparaciones quirúrgicas. Las permeabilidades primarias (PP) y secundaria (PS) a 6, 12 y 24 meses, fueron PP: 76.2%, 64.9%, 57.5% y PS: 86.4%, 81.2%, 74.7%, respectivamente. De total de los procedimientos nefrología obtuvo respecto a cirugía vascular un adecuado grado de concordancia en el 93.6 % de los casos (índice Kappa: 0.886). Los factores preoperatorios significativos entre los casos coincidentes y no coincidentes fueron la edad (P = 0.022) y el diámetro arterial (P = 0.032). El subgrupo de valoraciones no coincidentes entre nefrología y cirugía vascular (39 casos), presentaron una similar PP (a 2 años: 59,2% vs 41.3%, P = 0.099) pero peor PS (a 2 años: 76.6% vs 55.4%, P = 0.005).

ConclusionesNo se observaron diferencias significativas observador dependiente (nefrólogo vs. cirujano vascular) en la toma de decisiones en cuanto al acto quirúrgico a realizar (93.6% de coincidencia), y los casos discordantes presentaron peor permeabilidad secundaria. Tras una formación específica, el equipo de coordinación de nefrología puede realizar una adecuada optimización de los recursos socio sanitarios reservando las derivaciones a cirugía vascular para aquellos casos de mayor complejidad.

Different studies have shown that hemodialysis patients with native arteriovenous fistulas (AV) as definitive vascular access (VA) have a longer patency time and fewer associated complications.1,2 Current Spanish clinical guidelines on VA recommend the creation of different multidisciplinary teams dedicated to VA made up of nephrologists, vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists and advanced practice nephrological nurses.3 In this regard, different publications conclude that coordination between the different specialties allows better optimization of results in the field of VA.4–7

One of the main objectives of any functional vascular access unit (FVAU) is to promote the implementation of native AV fistula (nAVF). Some of the most important modifiable factors are the availability of an experienced and involved vascular surgery team,8,9 and early referral to advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) clinics,10 as well as the modification of different organizational models aimed at better optimization of vascular access outcomes.11 In addition to the evolution and progression of renal function, other factors intrinsic to each hospital center should be taken into consideration, such as the management of waiting times in the vascular surgery department or the intrinsic characteristics of each patient.12 Undoubtedly, all these factors would result in fewer patients with central venous catheters and fewer refusals for nAVF implantation. This last factor is of great importance, since according to the recent article published by Arenas MD et al.,13 patient refusal represents the main cause (36%) for not achieving the VA standards proposed by the current Spanish VA guidelines.3

In this context of increasing demand for care, one of the main threats to the system is the overcrowding of outpatient vascular surgery consultations. Given the implementation of a monographic and multidisciplinary VA consultation involving different professionals, it was hypothesized that a correct assessment by the nephrology team could help to relieve the pressure on vascular surgery care. In this sense, the primary objective of the present study was to evaluate the degree of concordance between nephrologists and vascular surgeons in relation to the vascular surgical procedure indicated in outpatient clinics and finally being performed. Secondarily, we also analyzed preoperative factors between coincident and non-coincident cases. To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates this new role of the coordinating team of a functional VA unit from this perspective.

MethodsThe functional vascular access unit of our center is integrated by a coordination team formed by nephrology (nephrologist and advanced practice nephrological nursing) that establishes a comprehensive and multidisciplinary care with the rest of the specialists in the field of vascular access. Our unit attends different patients both from our direct care area and as support for other centers in Catalonia, the latter representing 45–50% of the total surgical activity. Fig. 1 shows a diagram of how our vascular unit works. Among the different resources, we have 2 weekly monographic consultations with the support of vascular surgery on another floor for the referral of more complex consultations on the same day, with the aim of avoiding new appointments and travel for the patient. Our surgical staffing is 10–11 operating rooms per month for vascular access surgical procedures (3–4 procedures/operating room), approximately half of which have anesthesiology resources.

Between the years 2021 and 2022, a total of 605 surgical procedures or repairs performed in our functional vascular access unit were evaluated. All patients who were evaluated by our unit and subsequently underwent surgery for the creation or repair of a vascular access were analyzed. Different sociodemographic and clinical data and time on the waiting list were recorded and analyzed. All patients were assessed independently by the nephrology team (medical coordinator of the unit) and subsequently by the vascular surgery team (surgery finally performed), performing a systematic physical and ultrasound examination following our preoperative assessment protocol based on the recommendations of the Grupo Español Multidisciplinar del Acceso Vascular (GEMAV guidelines3 and European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS14; finally, the vascular access creation proposal of each team was recorded. In cases assessed in outpatient clinics only by the nephrology team, the surgical procedure was scheduled with the indicated proposal. On the same day of the intervention, the vascular surgeons performed an ultrasound mapping in the operating room to validate the previous proposal made in consultations by the nephrology coordination team. Based on these data, the coincident and non-coincident cases were defined between the two groups, considering the location (distal vs. proximal), laterality, indication for creation, ligation or repair.

Portable ultrasound equipment SonoSite® M-Turbo and SII (Fujifilm) were used for outpatient evaluations. Both in the preoperative study (physical examination and ultrasound), as well as in the compliance with the different levels of care for referral, the standards set by the current Spanish vascular access guidelines3 were used.

After the intervention, postoperative follow-up was performed as usual in these cases. The patency, use of the VA, and the need for endovascular and/or surgical reintervention during the follow-up period until to the present date were recorded in our database. In patients outside our area, the post-surgical controls were performed in their referral centers. Successful use of the nAVF after the first 4–6 weeks of their creation was considered to be adequate clinical maturation. In each reference center, VA monitoring and follow-up was performed in patients with 5D CKD (hemodialysis) according to the classic first generation methods (alterations during the hemodialysis session), measurement of recirculations and/or on-line dose (Kt), or second generation by estimating vascular flow (Qa) using indirect dilutional techniques or Doppler ultrasound. Upon suspicion of probable dysfunction, our vascular unit was contacted to schedule endovascular or surgical resolution directly (urgent cases) or after evaluation as an outpatient. Patients with CKD 5 (predialysis stage) were followed up in tha ACKD clinic by their responsible physician after a control of maturation performed by the coordination team in the case of patients in the direct care area or by their referral nephrologist in outpatient centers.

Statistical analysisA description of the preoperative, intraoperative and follow-up variables was performed using means and ranges, or number and percentage. The degree of correlation in surgical indication (laterality, location and indication for creation/repair/closure) between the vascular surgery and nephrology teams was calculated using the kappa coefficient, and a comparison of the preoperative and follow-up variables was made between those cases in which the nephrological and vascular surgery assessment was coincident or non-coincident, using Chi-square test for proportions and T-Test for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to calculate maturation, primary patency (PP) and secondary patency (SP), as well as Cox regression analysis to compare matched and mismatched cases, using the SPSS® v. 23 statistical package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), comparing both groups and searching for independent predictors of mismatch. Ligatures were excluded fr calculations ofmaturation and patency. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsA total of 605 AV creations or repairs performed were analyzed, 67% males with a mean age of 69.3 ± 13.1 years (21–94). In relation to cardiovascular risk factors we found a 91% of hypertension, 50.8% dyslipidemia, 47% diabetes mellitus, 15.7% ischemic heart disease, 10.9% atrial fibrillation, 8.4% peripheral vascular disease and 6.4% cerebrovascular disease. A total of 24.3% of the patients were receiving treatment with an antiplatelet agent and 13.9% were on anticoagulants.

A 61.6% (373) of the surgical procedures were performed in patients on hemodialysis, 29.2% (177) in ACKD and 9.1% (55) in renal transplant recipients, particularly surgical ligatures. A f 66.6% (403) of the interventions were performed under local anesthesia and 33.4% (202) with anesthesiologist requirements by means of locoregional blockades. Of the total number of surgical procedures there were 74 nAVF ligation (12.2%), 207 distal nAVF (34.3%), 237 proximal nAVF (39.2%), 35 repairs (5.7%), 41 pAVF (6.7%) and 11 other procedures (1.9%) were performed. Table 1 summarizes the percentage of compliance of the different levels of care according to the standards of the current Spanish VA guidelines.3

Compliance with response times according to severity level recommended by Spanish nephrology guidelines.3

| Level | Response (time elapsed) | Indications | Percentage of compliance |

|---|---|---|---|

| N0Urgent | ≤48 h | Serious complications IQx | 5/6 procedures (80%) |

| N1Priority | 2 weeks | FG <10 ml/min (functional VA).Rapidly worsening FG (functional V)G4 Thieving SyndromeComplicated AV fistula ligatures | 67/81 procedures (82.7%) |

| N2Preferred | 6 weeks | GFR: 10−15 ml/min (AV fistula)G3b Theft Syndrome | 139/142 procedures (97.8%) |

| N3Programmed | 3 months | FG ≥15 ml/min (functional VA).ERC 5D tunneled CVC carriersUncomplicated AV fistula ligaturesResection of AV fistula venomas | 376/376 procedures (100%) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVC, tunneled central venous catheter; GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min); AVF, Arteriovenous fistula; GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min).

The mean time on the waiting list was 16.4 ± 11.5 days (0–76) for native AV fistula and 16.7 ± 12.4 days (2–58) for pAVF. Excluding ligatures from further analysis, adequate maturation at 1 month was achieved in 87.6% of cases. During the postoperative follow-up, a total of 158 endovascular procedures and 17 surgical repairs were performed. The PP and SP obtained at 6, 12 and 24 months, were PP: 76.2, 64.9 and 57.5%, and PS: 86.4, 81.2 and 74.7%, respectively.

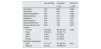

Of the total surgical procedures, nephrology obtained an adequate degree of concordance with respect to vascular surgery in 93.6% of the cases with a kappa index of 0.886. As shown in Table 2, the cases with greater discrepancies in the assessments were older (72.7 vs. 69.2 years; p = 0.022) and with greater arterial diameters (3.99 vs. 3.24 mm; p = 0.032); that is, greater discrepancies in cases with greater age and greater arterial diameters. In Fig. 2, it is shown how the subgroup of mismatched assessments between nephrology and vascular surgery (39 cases), presented similar PP (at 2 years: 59.2 vs. 41.3%; p = 0.099), but worse SP (at 2 years: 76.6 vs. 55.4%; p = 0.005).

Preoperative factors between matched and mismatched cases.

| Non-matching | Coincident | Value of p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 39 | n = 566 | ||

| Sex (male) | 72% | 68% | 0.594 |

| Age (years) | 72.7 | 69.2 | 0.022 |

| Arterial hypertension | 95% | 91% | 0.408 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 49% | 47% | 0.869 |

| Dyslipemia | 54% | 51% | 0.705 |

| Level of urgency | 2.46 | 2.48 | 0.871 |

| Artery diameter (mm) | 3.99 | 3.24 | 0.004 |

| Venous diameter (mm) | 3.09 | 3.33 | 0.274 |

| Location | |||

| Proximal | 23 (8.4%) | 250 (91.6%) | 0.028 |

| Distal | 16 (8.3%) | 176 (91.7%) | |

| Repair | 0 (0%) | 53 (100%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 12 (100%) | |

| Closing | 0 (0%) | 75 (100%) | |

| Anesthesia requirement | |||

| Local | 31 (7.7%) | 371 (92.3%) | 0.201 |

| Regional | 8 (4.05) | 194 (96.0%) | |

The present study defines a new role for the nephrology coordination team in the preoperative evaluation of the implantation of new vascular accesses, ligatures or surgical repairs. According to the results obtained, specific training enables adequate concordance with the vascular surgery team in both preoperative mapping and decision making as well as optimal management of waiting lists matching the standards set by current VA guidelines.3

Different preoperative factors such as advanced age, diabetes mellitus, female sex, coronary artery disease, peripheral vasculopathy and small venous and/or arterial diameters, as well as distal location, have been associated with lower patency rates after the creation of arteriovenous fistulas.15–18 Although clinical history and physical examination provide useful information, the addition of preoperative ultrasound mapping has been shown to significantly improve the results obtained.19 The application of Doppler ultrasound allows detecting the presence of arterial and venous stenosis that hinder the implantation of distal accesses. It is also useful in the determination of diameters and depth to define whether superficialization and/or transposition is required in one or two surgical procedures (>6 mm depth). In this regard, there are recommended a eminimum venous and arterial diameters of 2 mm for radio-cephalic AV fistulas, 3 mm for humero-cephalic or humero-basilar AV fistulas, and 4 mm for forearm grafts.14,20,21 Although diameter is the most studied prognostic factor, there are other ultrasound markers that can be useful, such as Doppler curve analysis, peak systolic velocity measurements, arterial study, as well as flow stimulation by reactive hyperemia.22

The control of vascular access maturation represents another of the main pillars of any functional vascular access unit. The main objective is to detect maturation failures subsidiary to endovascular or surgical repairs and to perform mapping in the first punctures. The establishment of active monitoring programs could significantly reduce the number of central venous catheters at the start of hemodialysis. Among the criteria for a clinincal definition of a mature native AV fistula, we propose obtaining a good efferent vein tract to perform punctures (8−10 cm23 and ultrasound with a vein diameter ≥5 mm, depth ≤6 mm and vascular flow (Qa) ≥500 ml/min.23–27 According to the data reported in the present study, by applying strict control in maturation, it can obtained adequate maturation rates > 85% of cases. Despite obtaining adequate SP rates, future studies will show us whether the creation of fistulas percutaneously28 or the implantation of new devices aimed at favoring maturation (VasQ™29,30 improve these results and are cost-effective.

There are only few comparative studies on VA. One of them is that of Asif et al.31 which evaluated the concordance obtained with systematic physical examination of native AV fistula dysfunction in a cohort of 142 patients with CKD stage 5D referred to their vascular clinic. Among the results obtained, it is worth noting that specific training in vascular access examination by the nephrology resident led to a kappa index of 0.78 in the diagnosis of proximal out-flow stenosis, confirmed by fistulography. According to the results obtained in our study, it is possible for the nephrology coordination team to obtain good levels of concordance (93.6%) with a kappa index of 0.886 in the preoperative assessment with preoperative mapping and decision making regarding vascular access complications (ligation with aneurysmorrhaphy or repairs). In our study the only 2 preoperative factors that were related to a greater discrepancies in assessments were age (p = 0.022) and arterial diameter (p = 0.032); that is, greater discrepancies in cases of older age and larger arterial diameters. Possibly these data are due to the more conservative attitude on the part of the nephrology team and the attempt to implant more distal fistulas by vascular surgery even in the subgroup of patients with more advanced age, or to the discrepancies in larger arterial diameters to force more distal accesses despite worse venous vessels. As shown in the results section, the subgroup of mismatched assessments (39 cases) had worse 2-year SP rates (76.6 vs. 55.4%; p = 0.005). In other words, when the assessments between the two groups coincide, the results are better because they are based on the application of the same criteria, whereas in the non-coincident groups, the results are worse because the cases have more complexity.

Another advantage of preoperative mapping performed by the nephrology team is the reduction in the average time for assessment in outpatient clinics, and the better selection of more complex cases that require a specific assessment by vascular surgery. The acquisition of this new care role in the vascular access would make it possible to optimize healthcare resources, avoiding the overcrowding of vascular surgery clinics, as well as ensuring adequate management of surgical waiting lists. According to the data obtained in our cohort, compliance percentages >80% were achieved at each of the different levels of care priority (N0-N3). Moving forward in the field of interventional nephrology, it would make sense to include preoperative assessment by nephrology as one of the standards in the current advanced PoCUS certification programs for vascular access.32

In conclusion, no significant differences were observed between observers (nephrologist vs. vascular surgeon) in decision-making regarding the surgical procedure to be performed (93.6% coincidence with a kappa index of 0.886), and the discordant cases presented worse SP. After specific training, the nephrology coordination team can adequately optimize social and health resources, preserving referrals to vascular surgery for those cases involving greater complexity.