Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is one of the main complications of diabetes, the main cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide. The etiopathogenesis of DKD is complex and multifactorial; recently, genetic susceptibility has gained relevance since certain ethnicities, such as Native Americans and Mexican Americans, have a higher risk of developing this disease. Numerous studies have described that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including those for ELMO1 and AGTR1 genes, could be associated with DKD.

ObjectiveTo carry out a systematic review of the scientific literature on the association of SNPs of the ELMO1 and AGTR1 gene with DKD in adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).

MethodsSystematic review in PubMed, Google Scholar, Worldwide Science, and Science Direct databases. The selection of publications was carried out following the guidelines proposed by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses). Original articles that reported results in the adult population with T2D were included. Information about the allelic and genotypic frequencies of the SNPs and their association with DKD was obtained.

ResultsThe polymorphisms most frequently associated with a DKD higher risk were rs741301, rs1345365, and rs10951509 for the ELMO1 gene, whereas the rs5186 and rs388915 for the AGTR1 gene.

ConclusionThe risk of developing DKD depends on several factors, including the genetic susceptibility conferred by the ELMO1 and AGTR1 gene polymorphisms, without ignoring the patient's lifestyle and environmental factors. The studies about these polymorphisms' association with DKD will allow a better understanding of non-modifiable risk factors for developing this disease and recognize the differences between different studied ethnicities, which would allow faster detection of patients with T2D susceptible to developing DKD, become early markers of kidney damage, as well as implementing preventive strategies on the most susceptible ethnicities.

La enfermedad renal diabética (ERD) es una de las principales complicaciones de la diabetes, es la principal causa de enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) y terminal (ERT) a nivel mundial. La etiopatogenia de la ERD es compleja y multifactorial; recientemente la susceptibilidad genética ha cobrado interés por observaciones en grupos raciales como los Nativo Americanos y México Americanos que poseen un riesgo mayor de desarrollar la enfermedad. Diversos estudios describen que polimorfismos de un solo nucleótido (SNP), que afecten a los genes ELMO1 y AGTR1, podrían estar asociados al desarrollo de ERD.

ObjetivoRealizar una revisión sistemática de la literatura científica sobre la asociación de SNPs del gen ELMO1 y AGTR1 con la ERD en pacientes adultos con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2).

MétodosRevisión sistemática en las bases de datos PubMed, Google Académico, Word Wide Science y ScienceDirect. La selección de las publicaciones se llevó a cabo siguiendo los lineamientos propuestos en la guía PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses). Se incluyeron artículos originales que reportaron resultados en población adulta con DM2. Se extrajo la información sobre las frecuencias alélicas y genotípicas de los SNP y su asociación con ERD.

ResultadosLos SNPs más frecuentemente asociados con un mayor riesgo para el desarrollo de ERD fueron los rs741301, rs1345365 y rs10951509 del gen ELMO1 y rs5186 y rs388915 del gen AGTR1.

ConclusiónEl riesgo de desarrollar ERD depende de diversos factores, entre los cuales debe considerarse la susceptibilidad genética conferida por los polimorfismos estudiados de los genes ELMO1 y AGTR1, sin dejar de lado, el estilo de vida del paciente y los factores ambientales. Los estudios de su asociación con polimorfismos permiten ampliar el conocimiento acerca de los factores de riesgo no modificables para desarrollar ERD y reconocer las variaciones entre las diferentes poblaciones estudiadas, lo que podría contribuir a la detección temprana de pacientes con DM2 susceptibles de presentar ERD, como marcadores tempranos de daño renal, así como la implementación de estrategias de prevención en las poblaciones étnicas más susceptibles.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a worldwide public health problem due to its high prevalence, complications and, morbidity and mortality. In 2015, there were approximately 415 million people affected by DM and it is estimated to increase 1.5 times by 2040, with higher incidence in low- and middle-income countries.1 Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is one of the main complications of DM. According to the guidelines of the Working Group for the Improvement of Global Kidney Disease Outcomes (KDIGO)2,3 and the American Diabetes Care Guidelines (ADA),4,5 DKD is defined as a decline in renal function assessed by a decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or the presence of albuminuria, which is considered the main marker of kidney damage and a leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide.6 Between 40 and 50% of patients with type 2 DM (DM2) and one third of patients with type 1 DM (DM1) develop ESKD.7 Most of these patients die due to cardiovascular causes even before reaching a final stage of DKD.8

The etiopathogenesis of DKD is complex and multifactorial, since different metabolic, environmental and genetic factors combine to trigger altered glomerular hemodynamics, inflammation, fibrosis and oxidative stress.3,7 The risk of developing DKD varies in different ethnic and racial groups. African American, Native American and Mexican American subjects have been reported to be at higher risk as compared to European Americans.9 These differences could be partially explained by genetic factors according to the findings of different genome-wide association studies.10,11 It has been described that genetic susceptibility confers a significant risk of DKD development, of which different single nucleotide change polymorphisms (SNPs) of the phagocytosis and cell motility 1 (ELMO1) gene and the angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AGRT1) gene are of particular relevance.12–14

In humans the ELMO1 gene is locatedon chromosome 7p14.1–14.2. It encodes the synthesis of a cytoplasmic protein, the ELMO1 protein, which interacts with cytokinesis proteins to promote phagocytosis and cell migration, as well as the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton.15

Several genome-wide association studies have linked ELMO1 SNPs to the susceptibility for the development of DKD in different populations.16 However, the role of the ELMO1 gene in the pathogenesis of the disease is not entirely clear; while some studies indicate that increased ELMO1 expression favors the development of DKD,17,18 others support that ELMO1 expression has a protective effect at the renal level, mainly under hyperglycemia conditions, by protecting endothelial and glomerular cells from apoptosis.16

The AGTR1 gene, in humans, is located on chromosome 3q24 and is coding for angiotensin II receptor 1 (AT1), the main effector of the actions of angiotensin type II (Ang II) at the systemic and local level. Once Ang II binds to the AT1 receptor, it produces vasoconstriction and stimulates the synthesis of aldosterone and vasopressin, in addition to favoring tubular reabsorption of sodium. Other effects include the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, triggering responses that regulate vascular resistance, blood pressure and GFR.19 It has been described that polymorphisms in the AGTR1 gene increase susceptibility to the development and progression of DKD through mechanisms such as oxidative stress and hemodynamic factors, such as glomerular hypertension that causes an alteration in the autoregulation of the renal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS).20

The identification of polymorphisms in the ELMO1 and AGTR1 genes associated with increased susceptibility to develop DKD could be useful for the assessment of the clinical course of patients with DM2 and to stablish appropriate guidelines for follow-up and prevention of complications.

The aim of the present study was to perform a systematic review of the scientific literature on the association of ELMO1 and AGTR1 gene SNPs with DKD in adult patients with DM2.

MethodologySources of informationThe first search of information was performed in June 2023, subsequently an update of the search was performed in March 2024, but no new published articles were found. The following databases were explored: PubMed, Google Scholar and Worldwide Science. For the case of AGTR1 a search in Science Direct was also included. The selection of publications was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)21 guidelines.

The following search terms were used: “diabetic kidney disease”, “diabetic nephropathy”, the word “polymorphism” was added, followed by the gene of interest, in this case “ELMO1” “(Engulfment and cell motility 1) ‘or’AGTR1” “(Angiotensin II Receptor Type I gene)” and the Boléan connectors “AND”, “OR” and “NOT”.

For the ELMO1 gene the search formulas in PubMed were: “diabetic kidney disease[Title/Abstract] OR diabetic nephropathy[Title/Abstract] AND polymorphism[Title/Abstract] AND ELMO1[Title/Abstract] OR Engulfment and cell motility 1[Title/Abstract] NOT review”; for the AGTR1 gene: “diabetic kidney disease[Title/Abstract] OR diabetic nephropathy[Title/Abstract] AND polymorphism[Title/Abstract] AND AGTR1[Title/Abstract] OR Angiotensin II Receptor Type I gene [Title/Abstract] NOT review”. In World Wide Science, the formulas were adapted to the characteristics of the databases. In ScienceDirect, the search formula used was: “diabetic kidney disease AND polymorphism AND rs5186 AND AGTR1 NOT reviews NOT COVID 19 NOT arterial hypertension NOT cancer”. For Google academic, the following formula was used: diabetic kidney disease OR diabetic nephropathy AND rs5186 OR A1166C NOT review.

Filters were applied for age (over 19 years of age), language (Spanish, English, Italian and Portuguese), date of publication, human studies and type of study design. Finally, articles on ELMO1 from other sources were also included and added manually.

Eligibility criteriaArticles published between 2000 and 2024 were included; this broad time range was used due to the limited information on polymorphisms of these genes associated with DKD. We included articles published in Spanish, English, Portuguese, or Italian that reported results in adult patients (>19 years) with a diagnosis of DM2. Studies performed in patients diagnosed with another type of diabetes, with a diagnosis of arterial hypertension, COVID-19 or cancer were excluded.

Quality criteriaThe quality assessment of the selected articles was based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)22 reporting criteria.

Extraction of informationInformation was extracted from the included articles independently by 2 of the coauthors. In case of discrepancies regarding the inclusion of any article, it was discussed with the rest of the coauthors to reach a consensus.

The information was extracted manually and concentrated in an Excel table, where the variables of interest were included: author, place and year of publication, characteristics of the population and study design, SNP studied, allelic and genotypic frequencies reported, as well as the main results by inheritance model: dominant, codominant, overdominant, recessive and additive.

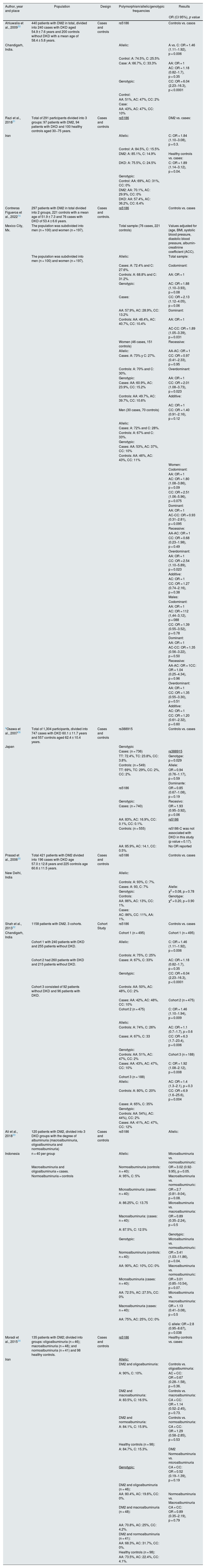

ResultsThe search was performed in 4 different databases. There were identified 111 studies, of which 4 were eliminated for duplicity and 89 during screening, 20 articles were finally included, 12 related to ELMO1 and 8 related to AGTR1. Among all the studies included in the review, 14 were identified from databases and 6 articles by other methods and included manually (Fig. 1).

Twelve articles on ELMO1 polymorphisms and DKD were reviewed and met the eligibility criteria (Table 1). The main SNPs reported were rs741301, rs1345365 and rs10951509. The rs741301 was evaluated in 11 studies, in 5 of them there was an association with DKD in populations from Egypt, Iran, Iraq, China or Japan10,13,23–25 and in the rest no association was demonstrated in populations from Poland, American Indians, China, Indonesia, Malaysia and Egypt.6,15,26–29 Regarding rs1345365, out of 5 studies, 3 reported an association in American Indian, African American and Chinese populations,11,26,27 while in the other 2 there was no association in Chinese and Iranian populations23,25; rs10951509 was evaluated in 3 studies, in which an association was found in Chinese, African American and American Indian populations.11,26,27

Studies that have reported the relationship between ELMO1 gene polymorphisms and the development of DKD.

| Author, year and place | Population | Design | Allele and genotype frequencies | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI), p value | ||||

| Bayoumy et al., 202013 | 200 DM2 without DKD (age 52.6 ± 6.2 years). | Cases and controls | rs741301 | Controls vs. cases |

| 200 DM2 with DKD (age 54 ± 6.1 years). | Allelic: healthy control: A: 66%, G: 34%. | Recessive allelic model (AA + AG vs. GG), adjusted for age, BMI, duration of diabetes, blood pressure: | ||

| Egipt | DM2 without DKD: A: 66%, G: 34%. | GG: was associated with DKD | ||

| 100 healthy controls (age 50.2 ± 4.8 years) | DM2 with DKD: A: 53.5%, G: 46.5%. | OR = 3.11 (1.16−8.30) p = 0.021 | ||

| 320 men | ||||

| 180 women | Genotypic: | G: was associated with DKD | ||

| Healthy control: AA: 42%, AG: 48%, GG: 10%. | OR = 1.82 (1.12–3.41) p = 0.004 | |||

| DM2 without DKD: AA: 43%, AG: 46%, GG: 11%. | ||||

| DM2 with DKD: AA: 31%, AG: 45%, GG: 24%. | ||||

| aHanson et al., 201026 | American Indians | Cases and controls | Study of Cases and controls | Cases and controls |

| USA | Cases and controls: | Family study | ||

| 107 DM2 with end-stage diabetic kidney disease. | Cases | Additive model, adjusted for confounding factors (age, gender and duration of diabetes) family | ||

| 108 DM2 without DKD | rs1345365 | Family study: | ||

| AA: 69%, AG: 30%, GG: 1% | rs1345365 | |||

| Cases with DKD: | A: 84%, G: 16% | A: OR = 2.42 (1.35−4.32), p = 0.0013 | ||

| 68% female, age 55.9 ± 8.9 years, duration diabetes 20.4 ± 7.1 years. | rs10951509 | |||

| AA: 66%, AG: 33%, GG: 1% | rs10951509 | |||

| Controls: | A: 82%, G: 18% | A: OR = 2.42 (1.31−4.48), p = 0.0022. | ||

| 56% women, age 58.9 ± 9.7 years, mean duration DM2 20.7 ± 5.5 years. | rs74741301a | |||

| CC: 30%, CT: 50%, TT: 20%. | rs741301: | |||

| Family study: | C: 55%, T: 45% | C: OR = 1.2 (0.81−1.77), p = 0.3518 | ||

| 141 DM2 with DKD, | rs1981740 | |||

| 416 DM2 without DKD | AA: 72%, AC: 27%, CC: 1% | rs1981740 | ||

| A: 85%, C: 15% | A: OR = 1.86 (1,.03−3.38), p = 0.0319 | |||

| With DKD: | ||||

| 62% women, 51 years ± 11.5 years, mean duration DM2 17.9 ± 7.9 years. | Controls | Estudio casos y controles | ||

| rs1345365 | rs1345365 | |||

| Without DKD: | AA: 72%, AG: 24%, GG: 4% | A: OR = 1.0 (0.59−1.70), p = 0.9957 | ||

| 65% women, age 42.2 ± 11.9 years, mean duration DM2 8 ± 7.2 years. | A: 84%, G: 16% | |||

| rs10951509 | rs10951509 | |||

| AA: 70%, AG: 26%, GG: 4% | A: OR = 0.95 (0.56−1.63), p = 0.8579 | |||

| A: 83%, G: 17% | ||||

| rs74741301a | rs741301 | |||

| CC: 29%, CT: 42%, TT: 29% | C: OR = 1.2 (0.3−1.75), p = 0.3352 | |||

| C: 50%, T: 50% | ||||

| rs1981740 | rs1981740 | |||

| AA: 77%, AC: 20%, CC: 3% | A: OR = 0.87 (0.49−1.52), p = 0.6210 | |||

| A: 87%, C: 13% | ||||

| Family study: | ||||

| DKD | ||||

| rs1345365 | ||||

| AA: 75%, AG: 24%, GG: 1% | ||||

| A: 87%, G: 13% | ||||

| rs10951509 | ||||

| AA: 73%, AG: 25%, GG: 2% | ||||

| A: 86%, G 14% | ||||

| rs74741301* | ||||

| CC: 38%, CT: 44%, TT: 17% | ||||

| C: 60%, T: 40% | ||||

| rs1981740 | ||||

| AA: 77%, AC: 21%, CC: 2% | ||||

| A: 88%, C: 12% | ||||

| Sin DKD | ||||

| rs1345365 | ||||

| AA: 63%, AG: 33%, GG: 3% | ||||

| A: 80%, G: 20% | ||||

| rs10951509 | ||||

| AA: 61%, AG: 35%, GG: 3% | ||||

| A: 79%, G 21% | ||||

| rs741301a | ||||

| CC: 28%, CT: 48%, TT: 24%. | ||||

| C: 52%, T: 48% | ||||

| rs1981740 | ||||

| AA: 71%, AC: 26%, CC: 2% | ||||

| A: 85%, C: 15% | ||||

| Kwiendacz et al., 20206 | Silesian population | Cases and controls | rs741301 | There was no association of the rs741301 polymorphism with DKD in the study and control groups, p = 0.6. |

| Poland | 272 patients with DM2 for more than 10 years (mean 14.1 years duration): | Alélica: | ||

| Cases: A: 66%, G: 34% | ||||

| Controls: A: 70%, G: 30% | ||||

| Genotípica: | ||||

| Cases: AA: 45%, AG: 41%, GG: 14% | ||||

| Controls: AA: 50%, AG: 40%, GG: 10% | ||||

| Leak et al., 200911 | 272 pacientes con DM2 por más de 10 años (media 14,1 años de duración): | Cases and controls | Set 1 | Controls vs. cases |

| EUA | Cases: | |||

| 117 DM2 with DKD | rs99996969311 | Dominant model | ||

| 155 DM2 without DKD | GG: 63.1%, GA: 32.5%, AA: 4.4%, G: 79%, A: 21% | Original and replication analysis found association of 4 SNPs in intron 13, p = 0.001−0.003, 1 SNP intron 1, p = 0.004, 1 SNP in intron 5, p = 0.002. | ||

| rs271717972 | Intron 1 | |||

| 170 women, 102 men | GG: 30.1%, GA: 49.7%, AA: 20.2%, G: 55%, A: 45% | rs9969311: | ||

| Mean age 63.7 years | rs1345365 | (GG vs. AG + AA) | ||

| GG: 49%, GA: 41.1%, AA: 9.8% | OR = 1.32 (1.11−1.57), p = 0.004 | |||

| Set 1 | G: 70%, A: 30% | |||

| Original analysis: | rs1981740 | Intron 5 | ||

| 577 African Americans with DM2 and chronic kidney disease, 596 African American non-diabetic controls, plus 43 European American controls and 45 Nigerian Yoruba samples for sample adjustment, non-diabetic and non-KDD | CC: 41.9%, CA: 44.9%, AA: 13.2%, C: 64%, A: 36% | rs2717972: | ||

| Gender of participants: | rs2058730 | (GG vs. AG + AA) | ||

| 658 women, | AA: 48%, AG: 44.9%, GG: 7.1% | OR = 0.75 (0.62−0.91), p = 0.002 | ||

| 515 men | A: 70%, G: 30% | |||

| rs10951509GG: 48.7%, GA: 41.6%, AA: 9.7%, G: 70%, A: 30% | Intron 13 | |||

| Set 2 | rs1345365: | |||

| Replication analysis: | Controls: | (GG vs. AG + AA) | ||

| 558 African Americans with DM2 and chronic kidney disease, 564 non-diabetic controls. | rs996969311 | OR = 0.76 (0.64−0.90), p = 0.001 | ||

| Gender of participants: | GG: 69.1%, GA: 27.5%, AA: 3.4%, G: 83%, A: 17% | |||

| 672 women, | rs2717972 | rs1981740: | ||

| 450 men | GG: 24.5%, GA: 52%, AA: 23.5% | (CC vs. AC + AA) | ||

| G: 51%, A: 49% | OR = 0.75 (0.63−0.89), p = 0.002 | |||

| Extension analysis: | rs1345365 | |||

| 328 African American DM2 without DKD | GG: 41.9%, GA: 47.8%, AA: 10.3%, G: 66%, A: 34% | rs2058730: | ||

| 326 without DM2 with end-stage chronic kidney disease. | rs1981740 | (AA vs. AG + GG) | ||

| CC: 34.2%, CA: 49.7%, AA: 16%, | OR = 0.78 (0.66−0.93), p = 0.003 | |||

| C: 59%, A: 41% | ||||

| rs2058730 | rs10951509: | |||

| AA: 42.3%, AG: 46.5%, GG: 11.1%, A: 66%, G: 34% | (GG vs. AG + AA) | |||

| rs10951509 | OR = 0.76 (0.64−0.89), p = 0.001 | |||

| GG: 40.3%, GA: 48.4%, AA: 11.3%, G 65%, A: 35% | ||||

| Set 2 | ||||

| Cases: | ||||

| rs9969311 | ||||

| GG: 62.9%, GA: 34.5%, AA: 2.6%, G: 80%, A: 20% | ||||

| rs2717972 | ||||

| GG: 28.4%, GA: 49.6%, AA: 22%, G: 53%, A: 47% | ||||

| rs1345365 | ||||

| GG: 46.5%, GA: 44.1, AA: 9.4%, G 69%, A 31% | ||||

| rs1981740 | ||||

| CC: 38.7, CA: 46.8%, AA: 14.5% | ||||

| C: 62%, A: 38% | ||||

| rs2058730 | ||||

| AA: 48.1%, AG: 42.5%, GG: 9.3%, A: 69%, G: 31% | ||||

| rs 10951509 | ||||

| GG: 46.2%, GA: 44.2%, AA: 9.6%, G: 68%, A: 32% | ||||

| Controls: | ||||

| rs9969311 | ||||

| GG: 69.2%, GA: 27.5%, AA: 3.2%, G: 83%, A: 17% | ||||

| rs2717972 | ||||

| GG: 23.4%, GA: 53.6%, AA: 2.3%, G: 50%, A: 50% | ||||

| rs1345365 | ||||

| GG: 40.1%, GA: 47.3%, AA: 12.6%%, G: 64%, A: 36% | ||||

| rs1981740 | ||||

| CC: 33%, CA: 50%, AA: 17% | ||||

| C: 32%, A: 68% | ||||

| rs2058730 | ||||

| AA: 41.7%, AG: 48.9%, GG: 9.4%, A: 66%, G: 34% | ||||

| rs10951509 | ||||

| GG: 41%, GA: 46.8%, AA: 12.3% | ||||

| G: 64%, A: 36% | ||||

| Yang et al., 202027 | 208 DM2 with DKD | Cases and controls | Allelic: | Controls vs. cases |

| China | 200 DM2 without DKD | rs10951509 | Dominant model, adjusted for confounding factors (age, gender, BMI, duration of DM2, family history and HbA1c) AA genotype vs. GG + AG. | |

| AGE 30−80 years, DM2 more than 10 years evolution, | Cases: A: 52%, G: 48%. | rs10951509 | ||

| 206 healthy, 30−80 years, | Controls: A: 76%, G: 24% | (GG + AG vs. AA) | ||

| Sex of participants with DM2: | OR = 1.738 (1.143−2.643), p = 0.010 | |||

| 239 men, | rs1345365 | |||

| 169 women | Cases: A: 68%, G: 32% | rs1345365 | ||

| Controls: A: 75%, G: 25% | (GG + AG vs. AA) | |||

| OR = 1.681 (1.106−2.555), p = 0.015 | ||||

| rs741301a | ||||

| Cases: C 34%, T 66% | Alelo G 10951509: | |||

| Controls: C 32%, T 68% | OR = 1.472 (1.081−2.004), p = 0.014 | |||

| Genotípica: | Allelo G 1345365: | |||

| rs10951509 | OR = 1.441 (1.062−1.956), p = 0.019 | |||

| Cases: AA: 49%, GA 39%, GG 12% | ||||

| Controls: AA: 60%, GA 32%, GG 8% | ||||

| rs1345365 | ||||

| Cases: AA: 49%, GA 38%, GG 13% | ||||

| Controls: AA: 59%, GA 32%, GG 9% | ||||

| rs741301 | ||||

| Cases: CC 11%, CT 47%, TT 42% | ||||

| Controls: CC 9%, CT 46%, TT 46% | ||||

| Mohammed et al., 202024 | Kerbala, Iraqi province | Cases and controls | rs741301 | Controls vs. Cases |

| Irak | 36 DM2 patients with DKD and 36 DM2 patients without DKD. | Codominant model (AA + AG + GG) | Dominant model | |

| Cases: AA: 8.33%, AG: 80.55%, GG: 11.11% | Patients with DKD | |||

| Sex of participants not mentioned | Controls: AA: 27.77%, AG: 66.66%, GG: 5.55% | (GG + AG vs. AA) | ||

| Dominant model (GG + AG) | OR = 5.28 (1.35−20.73), p = 0.017 | |||

| Cases: 91.66% | ||||

| Controls: 72.22% | Patients with DM2: | |||

| (GG + AG vs. AA) | ||||

| Recessive model | OR = 4.231 (1.06−16.7), p = 0.042 | |||

| Cases: AA + AG: 88.88%. | ||||

| GG: 11.11%. | ||||

| Controls: AA + AG: 94.44%. | ||||

| GG: 5.55%. | ||||

| Minor allele frequency | ||||

| Cases: 40.3% | ||||

| Controls: 38.95%. | ||||

| Hou et al., 201925 | 1325 patients total | Cases and controls | Cases: | Controls vs. Cases |

| China | 660 DM2 with DKD (378 men, 282 women, age 65.8 ± 13.8 years, duration of diabetes 10.1 ± 4.4 years) | rs741301 | Co-dominant model | |

| 665 DM2 without DKD (389 males, 276 females, age 66 ± 14.3 years, duration of diabetes 9.8 ± 4.7 years) | AA: 49.2%, AG: 40.2%, GG: 10.6% | rs741301 | ||

| A: 69.3%, G: 30.7% | AA: OR = 1 | |||

| rs1345365 | AG: OR = 1.68 (1.15−2.23) p < 0.001 | |||

| AA: 57.9%, AG: 35.6%, GG: 6.5% | GG: OR = 2.04 (1.29−2.82), p < 0.001 | |||

| A: 75.7%, G: 24.3% | ||||

| rs10255208 | A: OR = 1 | |||

| AA: 53.2%, AG: 37.1%, GG: 9.7% | G: OR = 1.75 (1.19−2.28), p < 0.001 | |||

| A: 71.7%, G: 28.3% | rs10255208 | |||

| rs7782979 | AA: OR = 1 | |||

| CC: 57%, CA: 36.7%, AA: 6.4% | AG: OR = 1.28 (0.88−1.77), p = 0.425 | |||

| C: 75.3%, A: 24.7% | GG: OR = 1.9 (1.30−2.59), p < 0.001 | |||

| A: OR = 1 | ||||

| Controls: | G: OR = 1.41 (1.06−1.92), p = 0.021 | |||

| rs741301 | ||||

| AA: 64.7%, AG: 30.4%, GG: 5% | rs1345365 | |||

| A: 79.8%, G: 20.2% | AA: OR = 1 | |||

| rs1345365 | AG: OR = 1.20 (0.80−1.81), p = 0.462 | |||

| AA: 62.4%, AG: 32.2%, GG: 5.4% | GG: OR = 1.51 (0.69−2.32), p = 0.613 | |||

| A: 78.5%, G: 21.5% | A: OR = 1 | |||

| rs10255208 | G: OR = 1.24 (0.77−1.95), p = 0.529 | |||

| AA: 64.1%, AG: 31.1%, GG: 4.8% | ||||

| A: 79.6%, G: 20.4% | rs7782979 | |||

| rs7782979 | CC: OR = 1 | |||

| CC: 61.5%, CA: 34.3%, AA: 4.2%, | CA: OR = 1.20 (0.84−1.72), p = 0.487 | |||

| C: 78.6, A: 21.4% | AA: OR = 1.29 (0.76−1.97), p = 0.641 | |||

| C: OR = 1 | ||||

| A: OR = 1.23 (0.82−1.76), p = 0.583 | ||||

| Mehrabzadeh et al., 201523 | Iranian population | Cases and controls | rs1345365 | Controls vs. Cases |

| Irán | 300 patients total | Cases: | Co-dominant model | |

| AA: 51%, AG: 41%, GG: 8% | Values adjusted for confounders (age, sex, creatinine, blood pressure and BMI) | |||

| 100 DM2 with DKD | A: 41.5%, G: 28.5% | rs1345365 | ||

| 100 DM2 without DKD | Controls: | AA: OR = 0.7 (0.4−1.3), p = 0.3 | ||

| 100 healthy | AA: 58%, AG: 37%, GG: 5% | AG: OR = 1.1 (0.6−2.0), p = 0.5 | ||

| A: 76.5%, G: 23.5% | GG: OR = 1.6 (0.5−5.2), p = 0.3 | |||

| Age 35−75 years | ||||

| Sex of participants not mentioned | rs741301 | rs741301 | ||

| Cases: | AA: OR = 0.5 (0.3−1.0), p = 0.05 | |||

| AA: 32%, AG: 42%, GG: 26% | AG: OR = 0.9 (0.5−1.6), p = 0.8 | |||

| A: 53%, G: 47% | GG: OR = 2.5 (1.2−5.4), p = 0.01 | |||

| Controls: | ||||

| AA: 45%, AG: 43%, GG: 12% | ||||

| A: 66.5%, G: 33.5% | ||||

| Kirtaniya et al., 202328 | 80 patients in total. | Cases and controls. | rs741301 | Controls vs. Cases |

| Indonesia | 40 DM2 without DKD | Cases: | AA vs. AG: OR = 0.793, p = 0.814 | |

| 40 DM2 with DKD | AA: 45.7%, AG: 51.5%, GG: 58.3% | AA vs. GG OR = 0.602, p = 0.674 | ||

| Casos: 25 hombres, 15 mujeres, edad 58.8 ± 6.8 años. | A: 47.6%, G: 54.4% | |||

| Controles: 23 hombres, 17 mujeres, edad 58.7 ± 7.7 años. | A vs. G: OR = 0.761, p = 0.509 | |||

| Controls: | Controls vs. cases (group 3 vs. groups 1 and 2) | |||

| AA: 54.3%, AG: 48.5%, GG: 41.7% | ||||

| A: 52.4%, G: 45.6% | GG: OR = 6.095 (2.45−15.12), p < 0,001 | |||

| G: OR = 2.366 (1.450−3.859), p = 0.001 | ||||

| There was no significant difference between patients with and without DKD (groups 1 and 2).Controls vs. Cases | ||||

| Omar et al., 202115 | 304 patients in total | Cases and controls. | rs741301 | |

| Egypt | Group 1: 100 DM2 with DKD | Group 1 | ||

| Group 2: 102 DM2 without DKD | Codominant model | |||

| Group 3: 102 healthy controls | AA: 38%, AG: 36%, GG: 26% | |||

| Dominant model | ||||

| 98 females and 204 males, age 48.78 ± 6.38 years | AA: 38%, AA/GG: 62% | |||

| Recessive model | ||||

| AA/AG: 74%, GG: 26% | ||||

| A: 56%, G 44% | ||||

| Group 2 | ||||

| Codominant model | ||||

| AA: 45.1%, AG: 33.33%, GG: 21.6% | ||||

| Dominant model | ||||

| AA: 45.1%, AA/GG: 54.9% | ||||

| Recessive model | ||||

| AA/AG: 78.4%, GG: 21.6% | ||||

| A: 61.7%, G: 38.2% | ||||

| Group 3 | ||||

| Codominant model | ||||

| AA: 62.7%, AG: 31.4%, GG: 5.9% | ||||

| Dominant model | ||||

| AA: 62.7%, AA/GG: 37.3% | ||||

| Recessive model | ||||

| AA/AG: 94.1%, GG: 5.9%, A: 78.4%, G: 21.6% | ||||

| Shimazaki et al., 200510 | Group 1: (n = 179) | Cases and controls. | 18 + 9170 A/G (rs741301) | Controls vs. Cases |

| Japan | 87 DM2 cases with DKD, age 57.9 ± 12.5 years, and 92 DM2 controls without DKD, age 62.7 ± 9.9 years. | Group 1 | (GG vs. AG + AA) | |

| Allelic: | Group 1 | |||

| Group 2: (n = 701) | Cases: A: 59%, G: 41% | OR = 6.69 (1.87−23.85) p = 0.001 | ||

| 459 DM2 cases with DKD, age 59.6 ± 13.5 years, and 242 DM2 controls without DKD, age 62.9 ± 12.5 years. | Controls: A: 72%, G: 28% | |||

| Genotypic: | Group 2 | |||

| Cases: AA: 35.6%, AG: 46%, GG: 18.4% | OR = 3.33 (1.81−6.15) p = 0.00005 | |||

| Controls: AA: 47.8%, AG: 48.9%, GG: 3.3% | ||||

| Group 2 | ||||

| Allelic: | ||||

| Cases: A: 61%, G: 39% | ||||

| Controls: A: 70%, G: 30% | ||||

| Genotypic: | ||||

| Cases: AA: 37%, AG: 47%, GG: 15.9% | ||||

| Controls: AA: 45%, AG: 49.6%, GG: 5.4% | ||||

| Yahya et al., 201929 | 652 patients in total. | Cases and controls. | rs741301 | Controls vs. Cases |

| Malasia | 227 from Malaysia (96 with DM2 without DKD and 131 with DM2 plus DKD), age 32−83 years. | Malaysia | Malaysia | |

| Allelic: | Multiplicative model | |||

| 203 from China (95 with DM2 without DKD and 108 with DM2 plus DKD), age 36−89 years. | Cases: A: 60.3%, G: 36.7% | Genotype: | ||

| Controls: A: 59.4%, G: 40.6% | 1.369, p = 0.5043 | |||

| 222 from India (136 with DM2 without DKD and 86 with DM2 plus DKD), age 35−86 years. | Genotypic: | Allele: | ||

| Cases: AA: 38.2%, AG: 44.3%, GG: 17.6% | 0.040, p = 0.8414 | |||

| Controls: AA: 36.1%, AG: 47.6%, GG: 16.3% | Dominant | |||

| 0.561, p = 0.4538 | ||||

| China | Recessive: | |||

| Allelic: | 0.359, p = 0.5491 | |||

| Cases: A: 60.6%, G: 39.4% | ||||

| Controls: A: 67.4%, G: 32.6% | China | |||

| Genotypic: | Multiplicative model | |||

| Cases: AA: 37%, AG: 47.2%, GG: 15.7% | Genotype: | |||

| Controls: AA: 44.2%, AG: 46.3%, GG: 9.5% | 2.203, p = 0.332 | |||

| Allele: | ||||

| India | 2 1.976, p = 0.1598 | |||

| Allelic: | Dominant: | |||

| Cases: A: 64.5%, G: 35.5% | 0.011, p = 0.9165 | |||

| Controls: A: 63.6%, G: 36.4% | Recessive: | |||

| Genotypic: | 1,080, p = 0.2986 | |||

| Cases: AA: 38.4%, AG: 52.3%, GG: 9.3% | ||||

| Controls: AA: 41.9%, AG: 43.4%, GG: 14.7% | India | |||

| Multiplicative model | ||||

| Genotype: | ||||

| 2.282, p = 0.3195 | ||||

| Allele: | ||||

| 0.040, p = 0.8414 | ||||

| Dominant: | ||||

| 0.274, p = 0.6007 | ||||

| Recessive: | ||||

| 1.396, p = 0.2374 |

DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; DKD: diabetic kidney disease; DKDT: diabetic end-stage renal disease; ESRD: end-stage chronic kidney disease; OR: odds ratio.

Regarding the polymorphisms of the AGRT1 gene and their association with DKD, 8 articles from different populations were included (Table 2). The most widely reported polymorphism was rs5186-C and a positive association with DKD was reported in populations from Mexico, India, Iran and Indonesia.14,30–33 However, such association was not found in populations from Iran, New Delhi, India and in the Japanese population.34–36 The rs388915 polymorphism reported in the Japanese population was significantly associated with DKD.36

Studies reporting the relationship between AGTR1 gene polymorphisms and the development of DKD.

| Author, year and place | Population | Design | Polymorphism/allelic/genotypic frequencies | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (CI 95%), p value | ||||

| Ahluwalia et al., 200930 | 440 patients with DM2 in total, divided into 240 cases with DKD aged 54.9 ± 7.6 years and 200 controls without DKD with a mean age of 58.4 ± 5.8 years. | Cases and controls | rs5186 | Controls vs. casos |

| Chandigarh, India. | Allelic: | A vs. C: OR = 1.46 (1.11−1.92), p = 0.006 | ||

| Control: A: 74.5%, C: 25.5% | ||||

| Case: A: 66.7%, C: 33.3% | AA: OR = 1 | |||

| AC: OR = 1.18 (0.82−1.7), p = 0.35 | ||||

| Genotypic: | CC: OR = 6.04 (2.23−16.3), p < 0.0001 | |||

| Control: | ||||

| AA: 51%, AC: 47%, CC: 2% | ||||

| Case: | ||||

| AA: 43%, AC: 47%, CC: 10% | ||||

| Razi et al., 201831 | Total of 291 participants divided into 3 groups: 97 patients with DM2, 94 patients with DKD and 100 healthy controls aged 30−75 years. | Cases and controls | rs5186 | DM2 vs. cases: |

| Iran | Allelic: | C: OR = 1.84 (1.10−3.08), p = 0.3. | ||

| Control: A: 84.5%, C: 15.5% | ||||

| DM2: A: 85.1%, C: 14.9% | Healthy controls vs. cases: | |||

| DKD: A: 75.5%, C: 24.5% | C: OR = 1.89 (1.14−3.12), p = 0.04. | |||

| Genotypic: | ||||

| Control: AA: 69%, AC: 31%, CC: 0% | ||||

| DM2: AA: 70.1%, AC: 29.9%, CC: 0% | ||||

| DKD: AA: 57.4%, AC: 36.2%, CC: 6.4% | ||||

| Contreras Figueroa et al., 202214 | 297 patients with DM2 in total divided into 2 groups, 221 controls with a mean age of 51.9 ± 7.3 and 76 cases with DKD of 53.4 ± 6.6 years. | Cases and controls. | rs5186 | Controls vs. cases |

| Mexico City, Mx. | The population was subdivided into men (n = 100) and women (n = 197). | Total sample (76 cases, 221 controls) | Values adjusted for (age, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, albumin-creatinine coefficient (ACC). | |

| The population was subdivided into men (n = 100) and women (n = 197). | Allelic: | Total sample: | ||

| Cases: A: 72.4% and C: 27.6%. | Codominant: | |||

| Controls: A: 68.8% and C: 31.2%. | AA: OR = 1 | |||

| Genotypic: | AC: OR = 1.88 (1.10−3.93), p = 0.08 | |||

| Cases: | CC: OR = 2.13 (1.12−4.05), p = 0.06 | |||

| AA: 57.9%, AC: 28.9%, CC: 13.2% | Dominant: | |||

| Controls: AA: 48.4%, AC: 40.7%, CC: 10.4% | AA: OR = 1 | |||

| AC-CC: OR = 1.89 (1.05−3.39), p = 0.031 | ||||

| Women (46 cases, 151 controls) | Recessive: | |||

| Allelic: | AA-AC: OR = 1 | |||

| Cases: A: 73% y C: 27%. | CC: OR = 0.97 (0.41−2.33), p = 0.95 | |||

| Controls: A: 70% and C: 30%. | Overdominant: | |||

| Genotypic: | AA: OR = 1 | |||

| Cases: AA: 60.9%, AC: 23.9%, CC: 15.2% | CC: OR = 2.01 (1.08−3.73), p = 0.023 | |||

| Controls: AA: 49.7%, AC: 39.7%, CC: 10.6% | Additive: | |||

| AC: OR = 1 | ||||

| Men (30 cases, 70 controls) | CC: OR = 1.40 (0.91−2.16), p = 0.12 | |||

| Allelic: | ||||

| Cases: A: 72% and C: 28%. | ||||

| Controls: A: 67% and C: 33%. | ||||

| Genotypic: | ||||

| Cases: AA: 53%, AC: 37%, CC: 10% | ||||

| Controls: AA: 46%, AC: 43%, CC: 11% | ||||

| Women: | ||||

| Codominant: | ||||

| AA: OR = 1 | ||||

| AC: OR = 1.80 (1.08−3.86), p = 0.09 | ||||

| CC: OR = 2.51 (1.06−5.96), p = 0.075 | ||||

| Dominant: | ||||

| AA: OR = 1 | ||||

| AC-CC: OR = 0.93 (0.31−2.81), p = 0.095 | ||||

| Recessive: | ||||

| AA-AC: OR = 1 | ||||

| CC: OR = 0.68 (0.23−1.98), p = 0.49 | ||||

| Overdominant: | ||||

| AA: OR = 1 | ||||

| CC: OR = 2.54 (1.10−5.89), p = 0.023 | ||||

| Additive: | ||||

| AC: OR = 1 | ||||

| CC: OR = 1.27 (0.74−2.16), p = 0.38 | ||||

| Males: | ||||

| Codominant: | ||||

| AA: OR = 1 | ||||

| AC: OR = 112 (1,44−3,12), p = 088 | ||||

| CC: OR = 1.39 (0.55−3.52), p = 0.78 | ||||

| Dominant: | ||||

| AA: OR = 1 | ||||

| AC-CC: OR = 1.35 (0.56−3.22), p = 0.50 | ||||

| Recessive: | ||||

| AA-AC: OR = 1CC: OR = 1.04 (0.25−4.34), p = 0.96 | ||||

| Overdominant: | ||||

| AA: OR = 1 | ||||

| CC: OR = 1.35 (0.55−3.30), p = 0.51 | ||||

| Additive: | ||||

| AC: OR = 1 | ||||

| CC: OR = 1.20 (0.61−2.32), p = 0.60 | ||||

| aOsawa et al., 200736 | Total of 1,304 participants, divided into 747 cases with DKD 60.1 ± 11.7 years and 557 controls aged 62.4 ± 10.4 years. | Cases and controls | rs388915 | Controls vs. cases |

| Japan | Genotypic | |||

| Cases: (n = 736) | rs388915 | |||

| TT: 72.4%, TC: 23.8%, CC: 3.8%. | Genotype: p = 0.029 | |||

| Controls: (n = 549) | Allele: | |||

| TT: 69%, TC: 29%, CC: 2%, CC: 2%. | OR = 0.94 (0.76−1.17), p = 0.59 | |||

| Dominante: | ||||

| rs5186 | OR = 0.85 (0.67−1.08), p = 0.19 | |||

| Genotypic: | Recesivo: | |||

| Cases: (n = 740) | OR = 1.93 (0.95−3.92), p = 0.06 | |||

| AA: 83%, AC: 16.9%, CC: 0.1%, CC: 0.1%. | rs5186 | |||

| Controls: (n = 555) | rs5186-C was not associated with DKD in this study (p value = 0.17). | |||

| AA: 85.9%, AC: 14.1, CC: 0.5%. | No OR reported | |||

| Prasad et al., 200635 | Total 421 patients with DM2 divided into 196 cases with DKD age 57.0 ± 12.8 years and 225 controls age 60.6 ± 11.5 years. | Cases and controls | rs5186 | Controls vs. cases |

| New Delhi, India | Allelic: | |||

| Controls: A: 93%, C: 7%. | ||||

| Cases: A: 93, C: 7% | Alelle: | |||

| Genotypic: | χ2 = 0.08, p = 0.78 | |||

| Controls: | Genotype: | |||

| AA: 86%, AC: 13%, CC: 1%. | χ2 = 0.20, p = 0.90 | |||

| Cases: | ||||

| AC: 86%, CC: 11%, AA: 1%. | ||||

| Shah et al., 201332 | 1158 patients with DM2. 3 cohorts. | Cohort Study | rs5186 | Controls vs. cases |

| Chandigarh, India | Cohort 1 (n = 495) | Cohort 1 (n = 495) | ||

| Cohort 1 with 240 patients with DKD and 255 patients without DKD. | Allelic: | C: OR = 1.46 (1.11−1.92), p = 0.006 | ||

| Controls: A: 75%, C: 25% | ||||

| Cohort 2 had 260 patients with DKD and 215 patients without DKD. | Cases: A: 67%, C: 33% | AC: OR = 1.18 (0.82−1.7), p = 0.35 | ||

| Genotypic: | CC: OR = 6.04 (2.23−16.3), p < 0.0001 | |||

| Cohort 3 consisted of 92 patients without DKD and 96 patients with DKD. | Controls: AA: 50%, AC: 48%, CC: 2% | |||

| Cases: AA: 42%, AC: 48%, CC: 10% | Cohort 2 (n = 475) | |||

| Cohort 2 (n = 475) | C: OR = 1.46 (1.10−1.94), p = 0.009 | |||

| Allelic: | ||||

| Controls: A: 74%, C: 26% | AC: OR = 1.1 (0.7−1.7), p = 0.6 | |||

| Cases: A: 67%, C: 33 | CC: OR = 6.3 (1.7−23.4), p = 0.006 | |||

| Genotypic: | ||||

| Controls: AA: 51%, AC: 47%, CC: 2% | Cohort 3 (n = 188) | |||

| Cases: AA: 43%, AC: 47%, CC: 10% | C: OR = 1.92 (1.08−2.12), p = 0.008 | |||

| Cohort 3 (n = 188) | ||||

| Allelic: | AC: OR = 1.4 (1.3−2.1), p = 0.3 | |||

| Controls: A: 80%, C: 20% | CC: OR = 6.9 (1.6−25.6), p = 0.004 | |||

| Cases: A: 65%, C: 35% | ||||

| Genotypic: | ||||

| Controls: AA: 54%), AC: 44%), CC: 2% | ||||

| Cases: AA: 41%, AC: 47%, CC: 12% | ||||

| Ali et al., 201833 | 120 patients with DM2, divided into 3 DKD groups with the degree of albuminuria (macroalbuminuria, oligoalbuminuria and normoalbuminuria) | Cases and controls | rs5186 | Allelic: |

| Indonesia | n = 40 per group | Allelic: | Microalbuminuria vs. normoalbuminuric: | |

| Macroalbuminuria and oligoalbuminuria = cases. | Normoalbuminuria (controls: n = 40): | OR = 3.02 (0.92-9.95), p = 0.05. | ||

| Normoalbuminuria = controls | A: 95%, C: 5% | Macroalbuminuria vs. normoalbuminuric: | ||

| Microalbuminuria: (cases: n = 40): | OR = 2.7 (0.81−9.04), p = 0.08. | |||

| A: 86.25%, C: 13.75 | Microalbuminuria vs. macroalbuminuria: | |||

| Macroalbuminuria: (cases: n = 40): | OR = 0.89 (0.35−2.24), p = 0.5 | |||

| A: 87.5%, C: 12.5% | ||||

| Genotypic: | ||||

| Genotypic: | Microalbuminuria vs. normoalbuminuric: | |||

| Normoalbuminuria (controls: n = 40): | OR = 3.41 (1.03−11.86), p = 0.04. | |||

| AA: 90%, AC: 10%, CC: 0% | Macroalbuminuria vs. normoalbuminuric: | |||

| Microalbuminuria (cases: n = 40): | OR = 3.01 (0.85−10.54), p = 0.07. | |||

| AA: 72.5%, AC: 27.5%, CC: 0% | Microalbuminuria vs. macroalbuminuria: | |||

| Macroalbuminuria (cases: n = 40): | OR = 1.13 (0.41−3.08), p = 0.5 | |||

| AA: 75%, AC: 25%, CC: 0% | ||||

| C allele: OR = 2.8 (0.95−8.67), p = 0.038 | ||||

| Moradi et al., 201534 | 135 patients with DM2; divided into groups: oligoalbuminuria (n = 46); macroalbuminuria (n = 48); and normoalbuminuria (n = 41) and 98 healthy controls. | Cases and controls | rs5186 | Healthy controls vs. cases: |

| Iran | Allelic: | |||

| DM2 and oligoalbuminuria: | Controls vs. oligoalbuminuria: | |||

| A: 90%, C: 10%. | AC + CC: OR = 0.67 (0.28−1.58), p = 0.36. | |||

| DM2 and macroalbuminuria: | Controls vs. macroalbuminuria: | |||

| A: 83.5%, C: 16.5%. | CA + CC: OR = 1.14 (0.52−2.45), p = 0.73. | |||

| DM2 and normoalbuminuria: | Controls vs. normoalbuminuria: | |||

| A: 84.1%, C: 15.9%. | CA + CC: OR = 1.29 (0.58−2.85), p = 0.53 | |||

| Healthy controls (n = 98): | ||||

| A: 84.7%, C: 15.3%. | DM2 | |||

| Normoalbuminuria vs. microalbuminuria | ||||

| Genotypic: | CA + CC: OR = 0.52 (0.19−1.39), p = 0.19 | |||

| DM2 and oligoalbuminuria (n = 46): | ||||

| AA: 80.4%, AC: 19.6%, CC: 0%. | Normoalbuminuria vs. Macroalbuminuria | |||

| DM2 and macroalbuminuria (n = 48): | CA + CC: OR = 0.89 (0.35−2.19), p = 0.79 | |||

| AA: 70.8%, AC: 25%, CC: 4.2%. | ||||

| DM2 and normoalbuminuria (n = 41): | ||||

| AA: 68.3%, AC: 31.7%, CC: 0%. | ||||

| Healthy controls (n = 98): | ||||

| AA: 73.5%, AC: 22.4%, CC: 4.1%. |

DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; DKD: diabetic kidney disease; DKDT: diabetic end-stage renal disease; ERCT: end-stage chronic kidney disease; OR: odds ratio.

Osawa et al.36 use the nomenclature to report the alleles of rs388915 based on the complementary strand, the rest of the authors report the alleles of this SNP based on the coding strand.

This review was performed to determine, according to the published literature, which ELMO1 and AGTR1 gene polymorphisms are associated with DKD in patients with DM2. In the case of the ELMO1 gene, a total of 12 articles were analyzed, including subjects aged 19–89 years from Iran, Iraq, Egypt, Poland, Indonesia, China, India, Malaysia, Japan, and the United States. The main ELMO1 polymorphisms associated with DKD were rs741301, rs1345365 and rs10951509. While for the AGTR1 gene, 8 articles were analyzed that included subjects between 19 and 75 years of age from India, Iran, Japan, Indonesia and Mexico. The AGTR1 gene polymorphisms associated with DKD were rs5186 and rs388915.

ELMO1 geners741301Located in the intron 18, it is one of the most studied polymorphisms in different populations. It has been found to be associated with a higher risk for the development of DKD in populations from Egypt, Iraq, Iran, China and Japan10,13,23–25; in these populations the G allele is associated with a higher risk, up to 2.3 times, and the GG genotype with a risk 2–6.6 times higher than carriers of the A allele (the AG heterozygotes or AA homozygotes). However, in populations such as the Indian American population of Arizona26 or in populations from Poland,6 China,27 Indonesia,28 and Malaysia,31 no association has been found. It is worth mentioning that the sample size in some of these studies was relatively small, such as the study by Kirtaniya et al. in 2023, which included 80 patients with DM2 in total, 40 cases and 40 controls28 and the study by Kwiendacz et al. in 2020, which included 272 patients with DM2, 117 cases and 155 controls.6 The 2021 study by Omar et al. also showed no significant association with DKD in patients with DM2; however, when performing a univariate logistic regression analysis comparing patients with and without DKD against healthy controls, a risk of up to 6 times higher was found in carriers of the GG genotype, being considered an independent risk factor.15

This discordance in the findings between the different populations may indicate that the associations depend not only on genetic factors, but also on their interactions between genes, on the complexity of the ELMO1 gene pathway in the development of DKD, as well as on other biological and environmental variables. Among the latter, ethylism, smoking and consumption of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are modifiable risk factors,37–40 whose role is not being considered in all studies and that could exert a synergistic gene-environment effect for the risk of DKD.25 For example, in China, Hou et al. in 2019 found that carriers of the G allele (GG/AG) compared to AA homozygous patients, the ethylism further increased the risk of developing DKD25.It is also important to consider the role of new nephroprotective drugs that could slow the damage and progression of DKD, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), Ang II AT1 receptor antagonists (ARA-II), sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors (iSGLT2) and glucagon-like peptide type 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists,41–44 whose role has also not been considered in most studies.

rs1345365This polymorphism located in intron 13 has also been studied in different populations, in American Indians from Arizona,26 African-American residents of the USA,11 in Iranian23 and Chinese25,27 populations, with inconsistent results. In China, Yang et al., in 2020, reported higher risk of DKD in carriers of the G allele (minor allele) although it was not maintained after adjusting for confounding factors; however, the GG + AG genotype (dominant model) was more prevalent in the group with DKD, even after adjusting the model for age, gender, BMI, duration of DM2, family history of DM2, and HbA1c levels, suggesting that the G allele might play an independent role in the development of DKD.27 This is in contrast with the reports by Hou et al. in 2019 and Mehrabzadeh et al. in 2015 in Chinese25 and Iranian23 populations respectively, where they found no significant associations of allele and genotypic frequencies with DKD. A limitation of the Iranian study is that the number of subjects was relatively small, since they included 300 subjects, 100 diseased controls, 100 healthy controls and 100 cases with DKD. It is important to highlight that the risk allele associated with DKD is not the same in the different study populations and even the proportions of the alleles can be found to be inverted, as observed in the study with American Indians by Hanson et al. in 2010, in which the A allele (major allele) increases the risk of developing nephropathy by 2.4 times.26 While in the African-American population in the USA, the A allele was found in a lower proportion and conferred a lower risk for DKD.11

rs10951509This polymorphism is located in intron 13. In Chinese population, Yang et al. in 2020 reported an increased risk for DKD in a dominant model; the GG + AG genotypes presented up to 1.7-fold increased risk after adjusting the model for confounding factors such as age, gender, BMI, duration of DM2, family history of DM2 and HbA1c.27 The allele frequencies, as well as the risk conferred by the alleles of this SNP, are also found to be inverted in African-American and Native American population residing in the USA as observed with rs1345365. In the study by Leak et al. in 2009, the A allele (minor allele) was associated with a lower risk of DKD, while in the study by Hanson et al. in 2010, it was associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk of nephropathy.11,26

Other polymorphismsIn the US African-American population the minor allele of rs9969311, was associated by up to 1.3 times increased risk of DKD, while other polymorphisms such as rs2717972, rs1981740 and rs2058730 were associated with a lower risk of nephropathy.11 The G allele (minor allele) and GG genotype of rs10255208 were associated with increased risk for the development of DKD of 1.4 and 1.9 times respectively in the Chinese population.25

The different findings highlight the role of genetic susceptibility conferred by polymorphisms in the development of DKD, because the risk locus and allele are not consistent across populations. The possibility that ELMO1 presents complex interactions with other biological variables should also be considered due to the different mechanisms by which it has been associated with renal damage, as well as possible gene–gene interactions between the different ELMO polymorphisms.26,28 It is also possible that different patterns of association may occur between populations due to variable linkage disequilibrium, resulting in functional variations occurring in different haplotypes, the so-called flip-flop phenomenon.45 Finally, it is likely that the combination of environmental exposures and genetic load determine the individual risk for the development and progression of DKD in different populations.25,26

Association of the ELMO1 gene and the pathogenesis of DKDAlthough the role of ELMO1 in the pathogenesis of DKD is not entirely clear, different authors have described and possible mechanisms involved in the development of the disease. The ELMO1 gene has been related to renal fibrosis and diabetic glomerulosclerosis through increased expression of profibrotic genes, such as the transforming growth factor gene β (TGF-β), COLA1 (which codes for collagen type 1), fibronectin, which generate renal tissue fibrosis, accumulation of extracellular matrix and thickening of the renal tubules and glomerular basement membrane, promoting the onset and progression of diabetic glomerulosclerosis (Fig. 2a). In Addition, ELMO1 has also been related to the inhibition of the expression of antifibrotic genes such as those of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase.10,17,18

Created in BioRender.com. Mechanisms of action of ELMO1 and AGTR genes in the genesis of DKD. (a) Mechanism of ELMO1 gene polymorphisms. ELMO1 polymorphisms alter ELMO1 gene expression and favor the development of interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and diffuse glomerulosclerosis through increased expression of profibrotic genes and inhibition of antifibrotic genes. (b) Mechanism of the rs5186 polymorphism of the AGTR1 gene. This polymorphism favors the instability in the transcription of the AGTR1 gene favoring the altered expression of the AT1 receptor, which causes a persistent activation of the RAAS, characterized by an increase in intraglomerular pressure and the ingury and loss of podocytes, damaging the architecture of the GBM favoring proteinuria.

GBM, glomerular basement membrane; TGFβ-1, transforming growth factor beta 1; RAAS, renin angiotensin aldosterone system.

Another pathway by which ELMO1 has been linked to the pathogenesis of DKD is through the production of reactive oxygen species, which alters glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.28 ELMO1 also functions as a regulator of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) activity, increasing the activity of the fibronectin promoter, with the consequent accumulation of fibronectin, which aggravates glomerular injury and the development of glomerulosclerosis.46 Studies in mice also suggest that the ELMO1 protein plays an important role in the pathogenesis of proteinuria by inducing glomerular lesions in glomerular epitheliai cells.18

However, this contrasts with the findings of an study performed in zebrafish and renal tissue from patients with diabetic nephropathy, where ELMO1 was found to protect the glomerulus from apoptosis and hyperglycemia-induced damage, since ELMO1 overexpression showed to produce reversibility of both structural and functional alterations caused by hyperglycemia in zebrafish renal cells.16 Thus, the role of ELMO1 in the pathogenesis of DKD still needs to be clearly established and it is possible that this new knowledge could help to determine the different associations of ELMO1 polymorphisms in different populations. However, it is clear that the ELMO1 gene SNPs, described in this review, alter its expression when found in intronic regions, which has been associated with lower or higher risk for the development of DKD, while in other populations no association has been demonstrated. Conversely, the complexity and the different pathways through which ELMO1 acts is important to be kept in mind in future studies, both the confounding variables, such as serum levels of ELMO1, COX-2, cytokinesis dedicator (DOCK180) and TGF-β1 proteins and to investigate the interaction between the different ELMO1 polymorphisms, as well as the interactions of ELMO1 with other genes, since this may affect the incidence of the DKD.28

AGTR1The main AGTR1 polymorphisms associated with DKD found in the literature reviewed were rs5186 and rs388915.

rs5186This polymorphism is located in the third exon of the AGTR1 gene in region 1166.47 The mutated allele is the minor C allele; the risk of developing the disease is increased in homozygous carriers of the minor allele.48

According to reports by Ahluwalia et al. from 2009, in the population from Indian, carriers of the C allele have a higher risk of DKD. In addition, CC homozygotes are 6 times more likely to present the disease.30 Similarly, in Iranian population, Razi et al. in 2018, reported that the risk of developing the disease is 1.84 times higher if at least one risk allele is present.31 In the study by Shah et al. in 2013, in patients of India origin, the CC genotype was associated with a 6-fold increased risk of DKD as compared with the AA genotype.32 By contrast, Osawa et al. in 2007, in Japan, and Prasad et al. in 2006, in India, found no significant association between the rs5186 polymorphism of AGTR1 and DKD.35,36

The research conducted by Contreras et al. in 2022 in a Mexican population, the C allele was associated with an increased risk of DKD, being higher in homozygotes (CC). Inheritance models adjusted for age, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (ACC) were analyzed, reported a risk of 1.89 times higher for the dominant model, while for the overdominant model it was 2.01 times higher in the total population. However, for the female population in the overdominant model, the risk increased to 2.54.14

Other studies found the same relationship between this SNP and the decrease in eGFR in men; such is the case of the 2011 study by Möllsten et al. in which it was found that the AA genotype increased the risk of DKD by 1.27 times in men. However, no significant association was observed in women.49 Other studies suggest a different association of overdominant model with sex.14 Hill et al. in 2016 mentioned that the prevalence of CKD is higher in women, due to their longer life expectancy, so that, when an advanced age is entered into the formulas to calculate eGFR, a more severe degree of CKD than the real one can be erroneously established.49 However, Carrero et al. in 2018 reported that the progression of CKD is usually more rapid in men, due to their unhealthy lifestyles; in contrast, estrogens confer certain protection against CKD.50

In Indonesia, Ali et al. in 2018 divided their study population of 120 patients according to the level of albuminuria. Nephropathy was associated with AC genotype and C allele.33 In Iran, Moradi et al. in 2015 also classified patients according to the degree of albuminuria and included a group of healthy individuals. In this study, there were no significant differences in genotypic frequencies.34 It is worth considering that it is estimated that 30% of patients with DM2 with renal disease will not present albuminuria, as reported in the NHANES III survey.51

rs388915The rs388915 polymorphism is located in the second intron of the AGTR1 gene, the major allele is G and the minor allele is A. However, Osawa et al., in 2007, reported their results based on the complementary strand, so the risk allele reported is T; in their Japanese population, they also investigated other polymorphisms of the ACE, AGT and AGTR1 genes and concluded that the increase in the number of risk alleles confers a greater probability of developing DKD.36

Association of the rs5186 polymorphism of AGTR1 with DKDThe association between polymorphisms of the AGTR1 gene with susceptibility to develop DKD is not yet clearly described. The most studied polymorphism of the AGTR1 gene and the most reported in the populations included in this review was rs5186. Several mechanisms have been proposed that could be involved in the interaction of this SNP and the increased susceptibility for DKD. The rs5186 polymorphism is located in region 1166 of the AGTR1 gene.47 This polymorphism is not located within a coding region, therefore it is not associated with a mutation that alters the amino acid sequence.52

MicroRNA-155 has been related to multiple diseases such as cancer, asthma, cystic fibrosis, among others53; however, recently it has been proposed that it could also be related with an abnormal regulation of the RAAS53 and the development of hypertension, and it could therefore play an important role in the pathophysiology of DKD. The region 1166 of the rs5186 polymorphism is recognized by the microRNA-155, which has the ability to undergo base pairing with the messenger RNA (mRNA) of the AGTR1 gene.47 When the ancestral A allele is present, binding to microRNA-155 suppresses transduction of the AGTR1 mRNA. However, when the mutated C allele is present, this mRNA suppression does not take place, so AGTR1 protein expression is not affected. Thus, it is proposed that microRNA-155 could regulate the expression of the translated proteins of the AGTR1gene.52,54 The AGTR1 gene encodes for the AT1 receptor protein, so a high amount of these will lead to greater activation of the RAAS and Ang II will bind more readily to the AT1 receptor.54 Further studies are important to fully elucidate the molecular mechanism of microRNA-155 and to assess whether there is a relationship with the development of DKD.

Other authors mention that this SNP could be related to instability in transcription, which would lead to an altered expression of the AT1 receptor, with excessive activation of the RAAS at the renal level, increasing the effects of Ang II on this organ.55 These effects include proliferation of mesangial cells and vasoconstriction of glomerular efferent arterioles, causing an increase in intraglomerular pressure. In addition, Ang II has non-hemodynamic effects such as inducing cell proliferation, fibrosis and inflammation.55,56 Glomerular capillary hypertension, induced by the action of Ang II, causes mechanical distension of the glomerular capillaries and subsequently podocyte injury.57 In addition, Ang II promotes the production of adhesion molecules and dysregulation in the synthesis and degradation of extracellular matrix, structural changes that if they are with chronic will lead to glomerular sclerosis.58

Finally, the loss of podocytes, together with glomerular hypertension and endothelial damage affects the architecture of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) favoring proteinuria59 (Fig. 2b).

ConclusionsThe main polymorphisms associated with the development of DKD were, the following in the case of the ELMO1 gene: rs741301, rs1345365 and rs10951509 and, for the AGTR1 gene, the most reported was rs5186.

The identification of the associations of genetic polymorphisms and DKD could be useful for the early detection in DM2 patients of a hig risk of developing RDD and to find early markers of renal damage.

The genetic susceptibility mediated by polymorphisms in certain populations confers certain risk for developing DKD; however, it is not the only factor involved in the pathophysiology of this disease.

Key conceptsGenetic susceptibility conferred by polymorphisms may be considered a risk factor for developing certain diseases in specific populations. However, genetic susceptibility is not the only factor involved in the development of these diseases.

The alleles of the major ELMO1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of RDD were rs741301-G, rs1345365-G and rs10951509-G in populations from Egypt, Iran, Iraq, China and Japan.10,13,23–25,27

The main polymorphisms of the AGTR1 gene that were associated with risk for DKD include rs5186-C in populations from India, Iran, Indonesia and Mexico, while in the Japanese population it was rs388915-C1532−38. ELMO 1 polymorphisms contribute to the development of interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and, finally, diffuse glomerulosclerosis through the expression of profibrotic genes and inhibition of antifibrotic genes.

AGTR1 polymorphisms cause AT1 receptor instability leading to persistent activation of the RAAS at the local level, finally conditioning GBM damage.

It is expected that, in the future, genetic polymorphisms could be used as early risk markers and detect the population with DM2 more susceptible to developing DKD.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector or non-profit entities.