To the Editor,

Paget’s disease (PD) is a focal bone remodelling disorder that can affect one or more bones.1 It is the second most common bone disease after osteoporosis, and its diagnosis usually derives from routine biochemical analyses, when elevated alkaline phosphatase (AP) levels are observed, or during imaging tests for other reasons.1-3

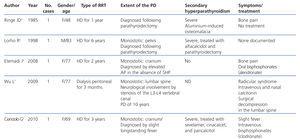

The incidence of PD in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is unknown. Few cases have been described in the medical literature,4-8 and in some of them PD was masked by secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHP),4-6 making its diagnosis quite difficult. With this in mind, we present the first case of a patient on peritoneal dialysis with coexisting polyostotic PD and SHP.

Our patient was a 72-year-old male with a history of arterial hypertension and gouty arthritis, who was diagnosed with CKD of unknown aetiology in 1990 and referred to our hospital in December 2007. In February 2008, he started continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Before starting dialysis, the patient had elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) and AP levels. He was diagnosed with SHP and initially received cinacalcet and calcitriol, followed by paricalcitol and cinacalcet. However, PTH levels remained high despite high drug doses, and were accompanied by persistently high AP levels.

In May 2011, he underwent computed tomography imaging for inclusion on the kidney transplant waiting list, and a sclerotic lesion was observed in the right iliac bone. A bone scintigraphy showed increased uptake of the radiotracer in the cervical spine, first finger of the right hand, left ulna, right sacroiliac joint, and, to a lesser extent, the external malleolus of the left ankle. Bone scans confirmed the presence of sclerotic lesions in the cervical spine, left ulna, and right sacroiliac joint (Figure).

During the follow-up period, the patient remained asymptomatic, without bone pain, fractures, or other complications. He was diagnosed with polyostotic PD. Given the absence of current indications for treatment, the patient is under periodic follow-up with strict surveillance and receives cinacalcet and calcifediol for SHP.

DISCUSSION

PD is a bone remodelling disorder characterised by a marked increase in bone reabsorption mediated by osteoclasts, followed by a compensatory increase in bone formation. The bone tissue created has altered biomechanical properties and structure and induces clinical complications such as pain and bone deformities, secondary osteoarthritis, fractures, headache, stenosis of the spinal canal, neurological compression symptoms, and sarcomatous degeneration.1-3 The prevalence of this disease in the general population ranges between 1.5% and 4.5% in individuals older than 40 years, and increases with age, with a slight predominance in males and its distribution varies depending on the geographical region.2 Follow-up of disease progression with periodical measurements of AP helps to determine the extent and level of activity of the disease.1 The primary treatment is bisphosphonates, drugs capable of regulating osteoclast activity.2 Randomised studies have suggested that these drugs are capable of reducing bone pain and decreasing AP levels.1 Scientific evidence does support treating patients with bone pain, neurological complications, hypercalcaemia due to prolonged immobilisation, patients that undergo elective orthopaedic surgery, and patients with localised activity in the base of the cranium, the spinal column, and long bones.2

Treatment in asymptomatic patients is a controversial topic. The PRISM study9 was a randomised trial that sought to standardise AP that compared the efficacy of bisphosphonates in an intensive treatment regimen that sought to normalize AP levels against symptomatic treatment in patients with bone pain. It analysed a cohort of 1324 patients and found that intensive treatment did not provide any clinical advantages (in terms of incidence of fractures, need for orthopaedic surgery, quality of life, bone pain, and auditory thresholds) compared to symptom management. As such, additional studies are needed to evaluate whether the effects of bisphosphonates translate into clinical benefits for the patient, and therefore, treating asymptomatic patients is not recommended.

In patients with advanced CKD, the prevalence of PD is unknown. Until now, only 5 cases have been reported in the medical literature (Table), four of which were on haemodialysis (HD)4-6,8 and one on peritoneal dialysis.7 In three of the patients on HD, SHP masked PD, and the diagnosis was made based on persistent AP elevation following parathyroidectomy.5,6,8 With respect to the treatment of these patients, one received intravenous and nasal calcitonin7 and the other two, intravenous bisphosphonates (Table).5,8 The indications for treatment were bone pain in two cases and a slight, long-standing fever in another case that was resolved upon treatment. No patients had adverse effects from treatment.

It is unclear the safety of bisphosphonates in CKD patients on dialysis.10 Some cases have been described of successful treatment of dialysis patients with bisphosphonates, but they very few cases and the majority of the patients were on HD. Since bisphosphonates are taken up by the bones at a rate of 50%-80%, they are capable of reducing bone remodelling, and this could lead to difficulties in repairing microfractures and deteriorated bone quality.11 Even in patients with CKD, the deposition of bisphosphonates in the bones is believed to be proportionally higher and is also correlated with the severity of SHP, which implies a risk of inducing adynamic bone disease in these patients11,12

In conclusion, SHP can mask the diagnosis of PD in CKD patients, so a high level of clinical suspicion in these patients, and in these cases, persistently high levels of AP originating in the bones, which tends to remain even after parathyroidectomy, may suggest the diagnosis of PD. However, in many cases, radiological images taken for other reasons may lead to the diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Figure 1. Pagets disease in chronic kidney disease

Table 1. Cases of Paget&