Dear editor:

Colonoscopy is critically dependent on adequate pre-procedural bowel cleansing and oral sodium phosphate bowel purgatives (OSP) have been used with good acceptance and efficacy for this purpose1. Among others metabolic and clinical disturbances described after the procedure, acute kidney injury may be a serious complication2,3. We present two cases of sodium phosphate induced acute renal failure.

Case 1

A 84 year-old male with a past history of stage 3 obstructive chronic renal failure, prostatic hypertrophy and hypertension, medicated with losartan, presented with complaints of six months weigh loss and changed bowel habits.

A colonoscopy was performed after preparation with oral sodium phosphate solution (Fleet phosphosoda®) with standard dose and its result was normal.

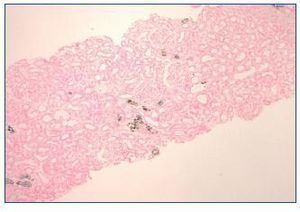

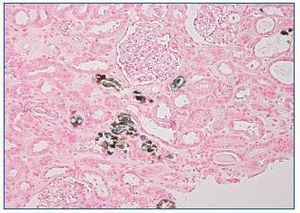

A week later, the patient reported pedal and orbital oedema and was observed on the emergency department. The physical examination was unremarkable except for hypertension (180/80 mmHg) and lower limbs oedema. Laboratory results showed haemoglobin 11.1 g/dl, serum urea 346 mg/dl, serum creatinine 9.2 mg/dl, serum sodium 130 mEq/L, serum potassium 6.5 mEq/L, serum phosphorus 6.6 mg/dl, normal serum calcium, serum bicarbonate 15 mEq/L and mild proteinuria. Serum and urine immunoelectrophoresis and immunologic study were normal. Renal ultrasound showed increased cortical echogenicity. Haemodialysis was initiated. Kidney biopsy showed minimal mesangial expansion. The tubules were mildly dilated and focal interstitial fibrosis was present. Von Kossa stain positive deposits were observed within the cytoplasm of tubular epithelial cells, tubular lumen and interstitium (figure 1 and figure 2). Immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin or complement.

We made the diagnosis of acute phosphate nephropathy secondary to administration of a sodium phosphate purgative.

Renal dysfunction didn’t improve after 7 months and the patient continues on regular haemodialysis.

Case 2

A 88 year-old male with a past history of prostatic hypertrophy and marginal zone-B cell lymphoma IV-B stage (treated with vincristine, cyclophosphamide and prednisolone for two cycles followed by second line therapy with rituximab and chlorambucil with disease progression) and stage 4 obstructive chronic renal failure. A virtual colonoscopy was performed after bowel preparation with Fleet phosphosoda®. Colonic diverticulosis was diagnosed.

Five days latter the patient reported lethargy and anuria and was admitted on the emergency department. He presented with drowsiness and was hypotensive, apyretic and oliguric. He presented inspiratory crackles on chest exam, distended and painful abdomen without guarding and lower limb oedema. Abnormal test results were hemoglobin 9.7 g/dL, leucocytes 17.1 x 109/L (87% neutrophils), platelets 70 x 109/L, serum creatinine 3.45 mg/dL, serum urea 106 mg/dL, serum calcium 4.5 mg/dl, serum phosphorus 18.3 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 3,028 U/L, c-Reactive protein 28.2 mg/dL, pH 7.3, bicarbonate 13.3 mEq/L and lactate 7.5 mmol/L; Urine dipstick was positive for blood, leucocytes and proteins. Renal ultrasound showed kidneys with enhanced echogenicity. Chest radiograph showed interstitial oedema and abdominal radiograph was normal.

Suspected severe urinary sepsis and acute kidney injury secondary to sepsis and phosphate nephropathy were assumed. Intravenous fluid was started, samples were obtained for culture and broad spectrum antibiotics were started. There was no clinical improvement and conservative measures were adopted.

DISCUSSION

Acute phosphate nephropathy (AphN) is a form of kidney injury that occurs after the use of bowel purgatives that contain oral sodium phosphate (OSP)2. OSP bowel solution (Fleet phosphosoda®) is a hyperosmotic purgative that has been used with good acceptance and efficacy in bowel cleansing before colonoscopy1. Both patients made the standard regimen (two 45 ml doses taken 10-12 h apart). Each dose contains monobasic and dibasic sodium phosphate providing the equivalent of 5,8 g of elemental phosphorus and 5 g of sodium3. Intestinal absorption occurs and transient hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia are found in all patients2. However, severe hyperphosphatemia, symptomatic hypocalcemia, hypernatremia, symptomatic hyponatremia, hypokalemia, anion-gap acidosis and acute kidney injury have been described after the procedure3-6. Two different clinical patterns of OSP-induced acute kidney injury have been described: early symptomatic and late insidious2.

The earlier form consists in an acute illness that manifests as changes in mental status, tetany, or cardiovascular collapse, usually in hours of bowel preparation, and patients present with severe hyperphophatemia and hypocalcemia. The second patient presented fit in this category. These patients require urgent fluid resuscitation, rapid correction of electrolyte disturbances, and sometimes dialysis. Despite aggressive fluid replacement and resuscitation our patient died. Some patients with this presentation survive and show renal function recovery2.

The second form is due to AphN with a more insidious onset (days to months) and is generally irreversible1. At the time of diagnosis, serum phosphorus and calcium levels are normal, unless measured within 3 days of bowel preparation. This was in fact the case of the first patient. As we found, the main pathologic finding in kidney biopsy is nephrocalcinosis demonstrated with the Von Kossa stain1.

Following reports of AphN Fleet phosphosoda® was voluntary withdrawn from US market in 200810. However OSP solution is still in use in some countries, as Portugal.

The pathophysiology of APhN involves transient hyperphospatemia, volume depletion exacerbated by concurrent ACE-I, ARB and diuretics, and elevated distal tubular phosphate and calcium concentrations1,8,10. Risk factors include advanced age, chronic kidney failure, dehydratation, female gender, diuretics, a history of colitis, and, probably, diabetes mellitus and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs1,10. Data indicate a high risk for chronic renal failure1,9,10. Our first patient needed long term haemodialysis. In Markowitz series none patient returned to their baseline creatinine levels and 19% progressed to ESRD at mean of 13.8 months after colonoscopy9.

In conclusion, these cases highlight the importance of AphN because such OSP are still used in clinical practice. Clinical presentation may assume two forms and, in any of these, consequences are serious and sometimes fatal. Strategies to prevent the development of APhN should be adopted and include avoidance in high-risk patients, adequate hydratation, dose minimization, increasing the interval between doses and possibly not administering ACE-I, ARB, diuretics and NSAID on the day before and the day after colonoscopy procedure6,10. It is also advisable to perform serum biochemistry tests after the procedure, in order to detect any renal or electrolyte abnormalities7.

Figure 1. Kidney biopsy. Von Kossa coloration (40x).

Figure 2. Kidney biopsy. Von Kossa coloration (100x).