Acquired perforating dermatosis (APD) is a frequent disorder in hemodialysis patients and the effect on the quality of life is poorly described. We investigated the prevalence of APD in hemodialysis patients, measured and compared APD-associated quality of life.

MethodsWe developed a prospective, observational, and descriptive study. We invited patients over the age of 18 in hemodialysis. Data was obtained from their electronic file and a dermatological examination was performed. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was applied. Descriptive analysis of demographic variables, clinical features, and dermoscopy findings, as well as comparison of DLQI scores, was made.

ResultsThe sample consisted of 46 patients, with a prevalence of APD of 11%. Patients with APD were leaner and younger compared to patients without APD. The time on hemodialysis was longer in patients with APD compared to those without APD, with a median of 90 versus 32 months (p = 0.015). The impact on quality of life was greater in patients with APD compared to those without APD, with some effect in all patients with APD and 33% in patients without APD (p = 0.001). Patients with APD had more frequent pruritus compared to those without APD (p = 0.007).

ConclusionsAge, time on hemodialysis and BMI are associated with the presence of APD. Patients with APD had a higher prevalence of pruritus and a greater impact on quality of life in dermatology compared to patients without APD.

La dermatosis perforante adquirida (DPA) es un trastorno frecuente en pacientes en hemodiálisis y el efecto en la calidad de vida está poco descrito. Investigamos la prevalencia de DPA en pacientes en hemodiálisis, medimos y comparamos la calidad de vida asociada a DPA.

MétodosDesarrollamos un estudio prospectivo, observacional y descriptivo. Invitamos a pacientes mayores de 18 años en hemodiálisis. Se obtuvieron datos de su expediente electrónico y se realizó exploración dermatológica. Se aplicó el Índice de Calidad de Vida en Dermatología (DLQI). Se hizo un análisis descriptivo de las variables demográficas, características clínicas y hallazgos de dermatoscopia, así como la comparación de los puntajes de DLQI.

ResultadosLa muestra fue de 46 pacientes, con una prevalencia de DPA del 11%. Los pacientes con DPA eran más delgados y jóvenes en comparación con los pacientes sin DPA. El tiempo en hemodiálisis fue mayor en los pacientes con DPA en comparación a los pacientes sin DPA, con una mediana de 90 versus 32 meses (p = 0,015). La afección en calidad de vida fue mayor en los pacientes con DPA en comparación a los pacientes sin DPA, con algún efecto en todos los pacientes con DPA y un 33% en los pacientes sin DPA (p = 0,001). Los pacientes con DPA tuvieron con más frecuencia prurito en comparación con los pacientes sin DPA (p = 0,007).

ConclusionesLa edad, el tiempo en hemodiálisis y el IMC se asocian con la presencia de DPA. Pacientes con DPA tuvieron una prevalencia más alta de prurito y mayor afección en la calidad de vida en dermatología en comparación con pacientes sin DPA.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a problem that affects millions of people in the world and affects multiple organs and systems, including the skin. It is estimated that more than 90% of patients with end-stage CKD have at least one dermatological problem,1 and depending on its extent it may have a significant impact on quality of life.2

The cutaneous manifestations of CKD are grouped into 2 categories. The nonspecific ones include pruritus, skin color changes, half-and-half nails and xerosis. The specific ones comprise acquired perforating dermatosis, bullous dermatosis, calciphylaxis and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.3

Among the specific manifestations, acquired perforating dermatosis (APD) stands out because is a rare disorder that has been scarcely described and is related to multiple systemic diseases, the most frequent are CKD and diabetes mellitus (DM).

APD is a group of skin disorders characterized by transepidermal shedding of skin materials, including elastic fibers, collagen fibers and keratin.4

The four primary forms of APD are described by the type of material removed and the type of epidermal disruption: Kyrle’s disease (keratin removal), reactive perforating collagenosis (collagen fibers), serpiginous perforating elastosis (elastic fibers), and perforating folliculitis (follicle contents with or without removal of elastic fibers).5 All four perforating disorders have been observed in adult patients with CKD and/or DM, as well as in other systemic disorders.

APD develops in adulthood, and is characterized by multiple umbilicated hyperpigmented papules and nodules with a central keratotic cap. The lesions have a predilection for the trunk and extremities and are also seen in areas that can be reached by scratching, are usually very pruritic, with positive Köebner phenomenon.5

One of the populations with the highest prevalence of APD are patients on renal replacement therapy; for example, in North America a prevalence of 4.56 to 10% has been reported, while in the United Kingdom, it has been described as 11%.

Quality of life in patients with kidney disease is affected at all stages,7 given that it is a progressive and debilitating condition, which also causes significant limitations in the physical and psychosocial well-being of patients.8 Quality of life in CKD is a predictive indicator of mortality and hospitalization.9

Patients with CKD undergoing hemodialysis experience a compromised quality of life due to the implications of the renal disease and its treatment. Moreover, they exhibit a high prevalence of skin problems.

It is known that even the most localized or asymptomatic skin lesions generate some alteration in patient well-being,10 so patients with CKD and chronic skin disease could have an additional effect on their perception of quality of life in the dermatological aspect.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of APD in our population of hemodialysis patients, to measure the quality of life associated with dermatologic disease in APD and to compare it with those patients without APD.

MethodsThis was a prospective, observational and descriptive study. The institution's research and research ethics committees approved the study. In the period from November 2020 to January 2021, we invited all 46 patients in the hemodialysis program at the hospital and all agreed to participate. The patients gave their informed consent. We obtained data from their electronic records, performed a dermatological examination, and the DermLite DL4 dermatoscope was used as an auxiliary tool to observe with greater clarity and describe the lesions found.

The diagnosis of APD was integrated in all cases by a dermatologist, using patient records, dermatologic examination, dermoscopy data and skin biopsy.

Patients without visual limitation filled out the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scale, and those with visual limitation were assisted by the investigator.

A descriptive analysis of demographic variables, clinical characteristics and dermoscopy findings was performed. Finally, statistical comparison of the DLQI scores of patients with and without a diagnosis of APD was performed. Data analysis was performed with IBM SPSS software® Statistics version 24.9.

Quality of Life Index Scale in DermatologyThe DLQI scale is a short and simple questionnaire that measures skin-related quality of life in patients with dermatological diseases. It consists of 10 questions covering areas such as symptoms, emotional effect, impact on daily activities, interference with work and study, interpersonal relationships and treatment. The scale has been widely used in clinical practice and research to assess the burden of illness in patients and the effectiveness of treatments. The DLQI has been shown to be reliable and valid in different patient populations and dermatologic diseases, and also in hemodialysis patients with pruritus. The total score of the scale ranges from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating greater impairment of the patient's quality of life. A score of 0 indicates that the disease does not affect the patient's quality of life, while a score of 30 indicates maximum impairment of quality of life.11

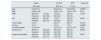

ResultsAll hemodialysis patients in our hospital agreed to participate, so we included a total sample of 46 patients and identified an APD prevalence of 11% (5 patients). Table 1 shows the main characteristics of our population.

General characteristics by diagnosis of APD.

| Global | No APD | APD | Value of p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% (46) | 89% (41) | 11% (5) | |||

| Age | 67 (62−74) | 69 (63−74) | 44 (32−56) | 0.0099* | |

| BMI | 24.46 ± 4.26 | 24.81 ± 4.21 | 21.56 ± 4.26 | 0.05** | |

| DM2 | Absence | 17% (8) | 15% (6) | 40% (2) | 0.158*** |

| Presence | 83% (38) | 85% (35) | 60% (3) | ||

| AH | Absence | 20% (9) | 17% (7) | 40% (2) | 0.222*** |

| Presence | 80% (37) | 83% (34) | 60% (3) | ||

| Time of DM2 | 24 ± 9 | 24 ± 10 | 26 ± 6 | 0.5791** | |

| AH time | 16 ± 8 | 16 ± 8 | 10 ± 4 | 0.0888** | |

| HD time (months) | 34 (13−70) | 32 (12−57) | 90 (55−115) | 0.015* | |

| Tobacco use | Absence | 57% (26) | 56% (23) | 60% (3) | 0.868*** |

| Presence | 43% (20) | 44% (18) | 40% (2) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | Absence | 63% (29) | 63% (26) | 60% (3) | 0.881*** |

| Presence | 34% (17) | 37% (15) | 40% (2) | ||

BMI, body mass index; DM2, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HD, hemodialysis; AH, arterial hypertension; APD, acquired perforating dermatosis.

Patients with APD were thinner and younger as compared to patients without APD (Table 1). Time on hemodialysis was longer in patients with APD compared to patients without APD, with a median of 90 versus 32 months (p 0.015). Type 2 diabetes (DM2), arterial hypertension (HTN), as well as the time of evolution of each, together with tobacco and alcohol consumption showed no difference between the groups.

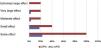

Quality of Life questionnaire. Quality of Life Index in Dermatology (DLQI)Thirty-two percent of the total population of hemodialysis patients reported effects on their quality of life due to skin problems (Table 2), and 40% reported some degree of pruritus. We found that the effect in quality of life due to dermatological disease was greater in patients with APD with some effect in 100% and 23% in patients without APD (p = 0.001) (Table 2). In the remaining categories constituting small, moderate, large and extremely large effect, a higher proportion of patients with the diagnosis of APD were affected compared to those without this diagnosis (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Pruritus and quality of life by diagnosis of APD.

| Global | No APD | APD | Value of p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% (46) | 89% (41) | 11% (5) | |||

| Pruritus | With itching | 40% (18) | 32.5% (13) | 100% (5) | 0.007 |

| Mild itching | 4% (2) | 5% (2) | 0% (0) | ||

| Moderate itching | 16% (7) | 15% (6) | 20% (1) | ||

| Severe itching | 11% (5) | 7.5% (3) | 40% (2) | ||

| Very severe itching | 9% (4) | 5% (2) | 40% (2) | ||

| Quality of life | Effect | 32% (16) | 23% (9) | 100% (5) | 0.001 |

| Small effect | 20% (9) | 18% (7) | 40% (2) | ||

| Moderate effect | 5% (2) | 3% (1) | 20% (1) | ||

| Very large effect | 5% (2) | 3% (1) | 20% (1) | ||

| Extremely large effect on life | 2% (1) | 0% (0) | 20% (1) |

APD: acquired perforating dermatosis.

Patients with APD had a higher incidence of pruritus compared to patients without this diagnosis, being 100 and 32.5%, respectively (p = 0.007). They also report more frequent severe or very severe pruritus (Table 2).

DiscussionWe found in our population a prevalence of APD of 11%, which is comparable to other populations,6,12 and illustrates a dermatologic disease that consistently affects the hemodialysis population worldwide.

In our population, we documented the association of younger age, lower body mass index (BMI) and longer duration on hemodialysis therapy with the presence of APD, variables that have not been reported in other studies on this disease, which could be related to the fact that these patients have had longer exposure to hemodialysis therapy and its deleterious effects.

We did not demonstrate association of APD with the presence of DM or HTN, probably in relation to the limited sample size.

Pruritus was present in 40% of all patients, this finding is similar to that described in other studies, Adejumo et al.,13 described a prevalence of pruritus of 42% in a population of patients with CKD in a tertiary hospital, similar to our population.

All patients with APD experienced some degree of pruritus, whereas only one third of patients without APD had this condition. APD in hemodialysis patients is thought to be triggered by two conditions: trauma induced by scratching and the microvascular condition of diabetes,14 so the finding of pruritus in all our patients with DPA could be a result of pruritus being a triggering condition for DPA.

In our population, 32% of the patients on hemodialysis reported dermatological quality of life issues, this finding is lower than that reported in other populations with similar characteristics, for example, Adejumo et al.,13 describe a 46% condition in their patients, this difference could be explained because the population described by Adejumo et al. were patients with different stages of renal disease, and our population included only patients on hemodialysis. In general, there is limited evidence in the medical literature regarding the measurement of quality of life due to dermatologic disease in patients with CKD and/or on renal replacement therapy.

Concerning the primary outcome, we observed a decline in the quality of life attributable to dermatologic conditions in all patients diagnosed with APD, as well as in a quarter of those without this diagnosis. These findings may indicate a higher likelihood of quality of life impairment among APD patients due to their frequently moderate to extremely severe skin conditions. It underscores the importance of diagnosing and treating APD to mitigate its impact on patients' quality of life.

One limitation of the study was the size of the population and the cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to establish causality. Another limitation is the inability to ascertain whether the decline in quality of life stemmed from more severe pruritus in the presence of APD or from the combined effect of these two factors.

ConclusionsIn our study we found that age, time on hemodialysis and low BMI are variables that are associated with the presence of APD.

Quality of life in relation to dermatologic disease in patients with APD was affected in all patients and this population had a high prevalence of pruritus.

APD is a common disease in patients with CKD on renal replacement therapy. It is characterized by being underrecognized and undertreated, in addition to having a great impact on quality of life, so we must make efforts to increase our knowledge about this dermatosis, and evaluate and treat these patients in a timely manner.

FundingResearchers' own resources.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.