Dear Editor, The phenomenon of immigration has experienced significant growth during the last decade, with the foreign population reaching 10% of the population living in Spain. Immigration has also brought us diseases that are uncommon in our country, which are sometimes only seen in old studies of medical pathology studied at degree level. This is one such case. We wanted to publish it due to its infrequency and academic value.

Dear Editor,

The phenomenon of immigration has experienced significant growth during the last decade, with the foreign population reaching 10% of the population living in Spain. Immigration has also brought us diseases that are uncommon in our country, which are sometimes only seen in old studies of medical pathology studied at degree level. This is one such case. We wanted to publish it due to its infrequency and academic value.

Clinical case

A 40 year old male patient from Bulgaria, with no family antecedents of any relevance. Patient history: AHTN, known for 12 years, heavy smoker for seven years, moderate drinker, and vesical tumour removed nine years ago in native country. Current illness: admitted to our hospital in 2006 for haematuria; advanced Chronic Renal Failure was confirmed.

Ultrasound showed small kidneys, poor corticomedullary differentiation, cortical hyperechogenicity and in the bladder, multiple solid nipple shaped lesions and therefore partial transurethral resection had been performed. An anatomopathological study showed low-grade urothelial carcinoma infiltrating the lamina tropria of the mucosa (papillary urothelial carcinoma, grade II, stage A.) Following this, the patient was treated with endovesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG.) Examinations in the pre-dialysis centre began in November 2006. The patient presented with polydipsia, polyuria and nycturia. The patient was working. Clinical examination found that the weight was 77.2kg and height 168cm; blood pressure 145-150/95mmHg; the patient had a median infraumbilical surgical scar; the rest (head, neck, lungs, heart, abdomen and extremities) were normal.

Blood tests from the laboratory showed: red cell count 3,570,000; HCT 32.7%; Hb 11.1g/dl; MCV 91.7fl; MCH 31.2pg; MCHC 34.1g/dl; reticulocytes 1%; IS 11.85%; ferritin 19.2ng/ml; vitamin B12 515pg/ml; folic acid 5.34ng/ml; leukocytes 6400 (S 65%, L 21%, M 7%, E 6%, B 1%), platelets 319,000, TPP 10.4 sec. (activity 121%, ratio 0.92); TTPA 30.5 sec. (ratio 1.02), fibrinogen 435mg/dl, urea 174mg/dl, creatinine 4.74mg/dl, Ccr 21.06ml/min, FRR 15.9ml/min; GF (MDRD-4) 14.8ml/min; Cl 108mEq/l; Na 139mEq/l; K 5.4mEq/l; HCO3 18.4mmol/l; Ca 8.48mg/dl; P 6.47mg/dl; PTHi 1,086pg/ml; alkaline phosphatase 111 IU/L; albumin 4.18g/dl; CRP 15.2mg/l; glucose 90mg/dl; cholesterol 277mg/dl; triglycerides 183mg/dl; uric acid 8.4mg/dl; GOT 13 IU/L; GPT 14 IU/L; GGT 18IU/L; total bilirubin 0.46mg/dl; HBsAg negative; HBsAc > 1000 U/L; HBcAc positive; anti-HCV negative; anti-HIV negative.

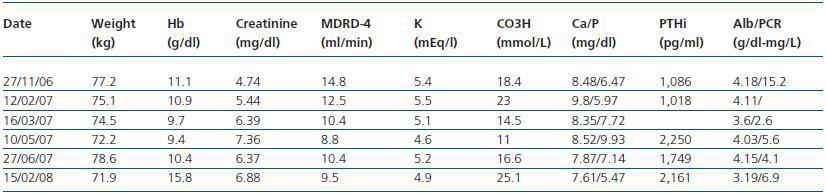

Urine: diuresis 4840ml/24 hours, pH 5, negative nitrites, proteins 2.7g/24 hours, sediment 8-15 leukocytes and erythrocytes per field; Cl 71mEq/l; Na 75mEq/l; K 19.8mEq/l; urea 5.57g/l; creatinine 29.7mg/dl. The patient was diagnosed with Balkan endemic nephropathy and conservative symptomatic therapy was begun. The patient was examined on several occasions, both in pre-dialysis clinic and in urology. Where vesical tumours were removed on two occasions. On 8 June 2007, an abdominal catheter was inserted and on 2 July 2007, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis was started. Two months later, the patient suffered his first episode of peritonitis due to Staphylococcus aureus which progressed slowly and suffered a relapse one month after the first episode. The progress was eventually satisfactory. In his last examination in the PD clinic the patient reported that he was feeling fine and had returned to work. The urological examination showed no abnormal results. The presence of an active tumour disease prevents the patient’s inclusion on the waiting list for a kidney transplant at the moment. The patient does not attend follow-ups when advised. The most significant analytical data on the patient’s evolution are included in table 1.

Discussion

Balkan endemic nephropathy, which was first described in 1956, is a chronic tubulointerstitial disease of unknown aetiology.

It is very often associated with urothelial atypia which can culminate in tumours of the urinary tract. Patients are from South-East Europe: Serbia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Croatia, Romania and Bulgaria, generally in the valleys of the River Danube and its surroundings. The prevalence of the disease in these areas is 0.5 to 4.4%. However, it can reach 20% if investigated more thoroughly; many of the patients are farmers.

The aetiology of the disease includes environmental and genetic factors. Among the first, the following have been studied: trace elements (lead, cadmium, selenium, silicon, etc.), viruses, plant toxins (aristolochic acid), fungi (ochratoxin A), aromatic hydrocarbons, heavy metals, etc.

Ochratoxin A is a mycotoxin that causes oxidative damage in the DNA and produces nephrotoxicity in experimental models.

Higher levels of this product have been found in the blood and urine of nephropathy patients from the Balkans and patients living in this zone. This product may be derived from food products. Aristolochic acid is a mutagenic and nephrotoxic alkaloid found in the Aristolochia clematitis plant. It has been linked to nephropathy endemic to the Balkans2 and nephropathy linked to Chinese herb nephropathy (which caused a disaster in Belgium at the start of the nineties, to such an extent that nowadays we talk of aristolochic acid nephropathy.)3,4 The theory of genetic factors is based on family cases, considering a type of polygenic inheritance. Candidate genes have been located in the 3q24 and 3q26 region; given the link with bladder carcinoma, mutations of the tumour suppressor gene p53 have been explored.

Many authors accept that the disease is familial but not hereditary. The etiopathogenic theory would be that of individuals who are genetically prone to and chronically exposed to a causal agent (aristolochic acid) found within these endemic areas. In terms of the anatomical pathology of the disease, as well as tubulointerstitial changes, focal and segmental glomerular changes and global sclerosis may occur.

Patients are generally aged between 30 and 50. One of the first signs is tubular dysfunction, characterised by increased elimination of low molecular weight proteins (beta 2-microglobulin and neopterin etc.)

Glycosuria, aminoaciduria and difficulties managing acid load may also appear. However it has been calculated that a reduction in concentration capacity, arterial hypertension and reduced glomerular filtration will only appear after 20 years.

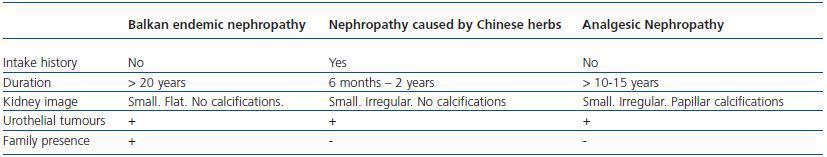

Anaemia, which is initially seen, increases as the disease progresses. There is not normally any infection of the urinary tract. Kidney size is initially normal, but decreases symmetrically in time, with smooth edges and without calcifications.There is a high incidence (2 to 10 times greater than in non-epidemic areas) of urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma, in which aristolochic acid is also involved.5 If there is no diagnosis of urinary tract tumour, it is advisable to carry out a urinary cell biology once or twice a year. Diagnosis is easy if you take into account, given the slow evolution of the disease, the fact that the patient lives in a certain area and there are tumours in the urinary tract. For differential diagnosis, two entities must be taken into account: Analgesic nephropathy and Chinese herb nephropathy, as shown in table 2, while, as previously mentioned, they can normally be explained by the causal factor itself: aristolochic acid.

When does not exist the diagnosis of tumor of urinary tract, urinary cytology has to be performed one or two times a year. The diagnosis is easy if it is thought about this disease, given the slow evolution , to live in a concrete zone and the presence of tumors in urinary tract. In the differential diagnosis it is necessary to remember two entities: analgesic nephropathy and nephropathy caused by chinese herbs, as shown in table 2, though, as it has been said, nowadays they tend to be explained by the same causal factor: the acid aristolochic, Balkan nephropathy and nephropathy caused by Chinese herbs.

Table 1.

Table 2.